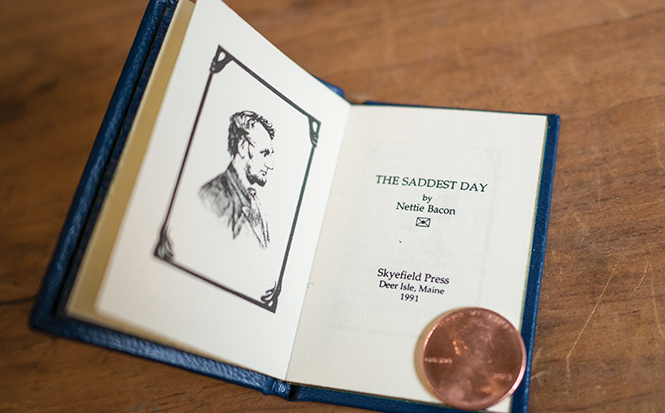

On Display: The Saddest Day

Miniature artist book

Photo by James Gehrt

On April 15, 1865, Antoinette (Nettie) Bacon, class of 1866, was returning to South Hadley in a public carriage when she learned a shocking piece of news: President Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated. That same day, Bacon began a letter to her brother Alonzo, explaining the confusion and grief the news had caused. “Pen can never express the feelings of the Northern people at this sad news,” she wrote. “What is to become of us!”

Pen can never express the feelings of the Northern people at this sad news. What is to become of us!

Nettie Bacon, class of 1866

The feelings of anger and shock that Bacon conveys in her letter are underscored by a sense of weariness. “The war,” she worried, “is farther from its close than we have thought.” In reality, the war had effectively ended six days before, when General Robert E. Lee surrendered at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia.

Bacon’s letter provides a remarkable glimpse into how the public received the news of Lincoln’s assassination and how long it took for information to travel. The reports she heard on April 15 were incomplete. Many people believed, for instance, that in addition to Lincoln, Secretary of State William H. Seward had been the victim of a successful assassination attempt. When she completed her letter two days later this fear was alleviated; however, Bacon’s anger toward the perpetrators of the crime and the southern “Rebs” who took such delight in the event remained. “Today,” she wrote, “has been I believe the very saddest day this nation ever saw.”

After graduating from Mount Holyoke, Bacon went on to teach among freed slaves for the American Missionary Association in Washington, North Carolina, and Port Royal, South Carolina.

More than a century later, in 1991, staff at Skyefield Press found Bacon’s letter among a stack of old papers in an antique shop and transformed it into a miniature artist book. Two copies of the book, entitled The Saddest Day, can be viewed at Mount Holyoke’s Archives and Special Collections.

—By Emily Wells ’15

This article appeared in the winter 2015 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

January 18, 2015

Leave a Reply