Women in the Lead

Overseen by Barbara Moakler Byrne ’76, the Women in Leadership Index is showing that the market is bullish on companies with women at the helm

Shortly before taking her company public in January 2014, Sheila Lirio Marcelo ’93 went on the road to get feedback from institutional investors—financial organizations that invest large amounts of money and wield considerable influence over markets. Sleep deprived from near-constant travel, she entered one meeting and went straight for the coffee pot. To be polite, she offered coffee to the other participants, too. After her male colleagues had introduced themselves, Marcelo was about to shake hands with the investors when they made a telling assumption: “You,” they told her, “must be the assistant.”

Marcelo smiled and corrected them. “I’m the founder and CEO of Care.com.”

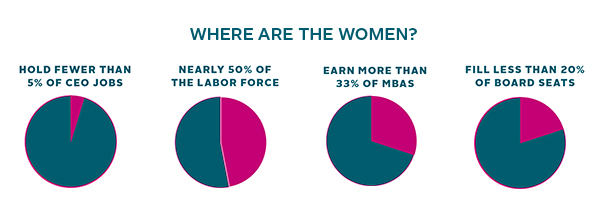

It wasn’t the first time that Marcelo—who heads the world’s largest online venue for finding caregivers—had been underestimated because of her gender. And her experience isn’t unusual in the business world, where most companies are run by men. In March 2015 fewer than 5 percent of chief executive jobs at leading US companies were held by women, and last year women filled just less than 20 percent of all board seats. Yet women make up nearly half the US labor force and earn more than a third of the MBAs awarded in this country.

“The United States in particular has been slow in getting more women in leadership positions at publicly traded companies,” says Barbara Moakler Byrne ’76, vice chair of investment banking at Barclays Bank. “We are still significantly underrepresented.”

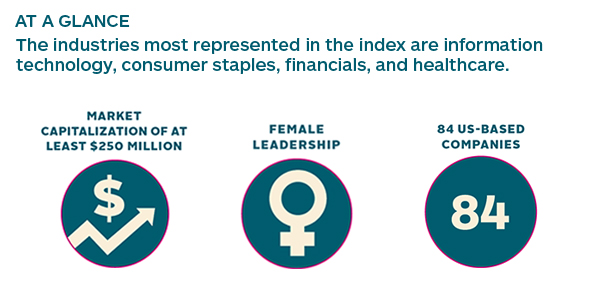

It’s a situation she is working to change. Named the fourth most powerful woman in finance by American Banker, Byrne is overseeing a new market-based approach to increasing the number of women in senior management. The initiative, Barclays Women in Leadership Index, consists of US-based public companies that have either a woman CEO or a board of directors that is at least 25 percent female. The index drives the performance of Barclays Women in Leadership Exchange-Traded Notes—unsecured debt obligations that trade on the New York Stock Exchange. The index was inspired by three younger female colleagues, who suggested launching a product for investors interested in making a statement about the value of gender diversity.

“We’re seeing a trend of people wanting to invest their money in a socially responsible manner,” says Byrne, who chairs Barclays Social Innovation Facility. “This index is creating a vehicle for that, if you’re a believer that women in leadership matters.”

The index includes major companies such as General Motors, PepsiCo, General Electric, Google, AT&T, and Monsanto. Its launch last July was covered by media outlets ranging from Bloomberg Business to Politico to Fortune. If it had existed in 2009, over the next five years it would have outperformed Standard & Poor’s 500 index, the leading indicator for the US stock market. That’s partly because the Women in Leadership Index is skewed toward consumer-product companies, Byrne says, with less representation from the energy sector, which has been hit hard by falling oil prices.

Women, in particular, may bring qualities to a board that result in better corporate governance.

Michael Robinson, Chair, Mount Holyoke Economics Department

But that may not be the only reason. A growing body of literature suggests that companies are more successful when their leaders include women. In its Women Matter research, published over the past seven years, the management consulting firm McKinsey found that companies with at least three women in senior management positions (a so-called critical mass) scored higher on measures of organizational excellence than those with no women in high-level roles. McKinsey also determined that the companies with the greatest gender diversity at the top generally had above-average financial results. Catalyst, a nonprofit organization that works to support women in the workplace, reported that from 2004 to 2008 the companies with the most women board members over time outperformed their least-diverse counterparts on multiple financial criteria. And a 2013 Thomson Reuters study concluded that companies with mixed boards did slightly better on the stock market than companies with no women serving on their boards.

A 2012 Credit Suisse analysis provides more evidence for the correlation between gender diversity and performance. It reveals that companies with female representation on their boards had higher stock prices and superior financial performance—including growth and return on equity—which is linked to profit. One possible explanation is that companies that are already doing well may be more inclined to appoint women to high-level positions. But there are likely other factors at play, too, according to the report. Among the most intriguing is that diverse teams tend to come up with stronger solutions, in part because those in the majority put more effort into examining issues when they know that they will be faced with a broader range of views.

Women, in particular, may bring qualities to a board that result in better corporate governance, says Mount Holyoke Economics Department Chair Michael Robinson, who teaches a course on women in business. “There seems to be a fair amount of evidence that women have different leadership styles and that a board with more women on it will behave differently.” For instance, women tend to be less hierarchical and to reach out to all stakeholders, including workers, which may help them make effective decisions.

The importance of gender-diverse leadership comes as no surprise to Mount Holyoke alumnae who are at the helm of companies. “Without it, you’re depriving yourself of half the world’s thinking, of half the world’s ability to solve problems,” says Maria Cirino ’85, cofounder and managing director of .406 Ventures, which invests in technology companies. “It’s like having half a brain.”

That’s especially crippling in a business environment that has become increasingly international. “If we’re going to keep up with the changing nature of markets and connect with our global client base, we need to be able to think beyond the classic white male banking structure,” says Fizzah Jafri ’99, global chief operating officer for fixed income research and economics at Morgan Stanley. “We need to hire women and people of different ethnic groups.”

Companies with female representation on their boards had higher stock prices and superior financial performance—including growth and return on equity—which is linked to profit.

Credit Suisse

Jafri notes that women often make strong managers because of their ability to multitask and build teams. In her own case, she tries to get to know employees on a deeper level, to understand what motivates and frustrates them, and to express interest in what’s happening in their lives. “I think we have a little more empathy. I think we’re good listeners, and that’s the basis for having a strong relationship,” Jafri says.

Marcelo, who is founder, chairwoman, and CEO of Care.com, says leaders must embrace both the analytical qualities traditionally viewed as male and the interpersonal strengths once considered traditionally female. “The blend of these skills is redefining leadership,” she says. “I think a lot of the leadership books are emphasizing the competencies that were formerly labeled women’s traits.”

Even today, however, those traits can be undervalued or misunderstood. In particular, women may respond more emotionally to situations, which some view as inconsistent with strong leadership. Jodie Pope Morrison ’97, president and CEO of Tokai Pharmaceuticals, has a different take on the matter. Early in her career at a drug company where Morrison worked as a researcher, a clinical-trial participant came in to talk about the impact of a medication the company had developed. One vice president was so moved that she became teary. Morrison and others in the audience viewed her reaction as showing how much passion she brought to the mission of improving people’s lives. “Seeing that showing emotion was acceptable was important,” Morrison recalls. “It was freeing.”

But many junior employees see no—or very few—women above them. Mary Francis ’86, who in May will become corporate secretary and chief governance officer of Chevron, says her colleagues have been supportive and helpful during her thirteen years with the company. Still, she says, “I can’t say I really had a mentor. Having more role models would have helped me visualize the position I wanted to be in and think about how to get there. I’ve kind of had to figure things out myself.”

Francis is most concerned about the dearth of women in the senior ranks of companies. While more women are being hired, they often drop out before attaining an upper-level position. That means fewer role models for the women who come after them. “It becomes harder and harder for women to pierce that ceiling,” she says.

Francis says companies need to take a hard look at what might be preventing women from advancing, including family obligations and lack of mentorship. Sometimes the barriers may be subtle. For instance, Francis’s path at Chevron included an assignment in Singapore, where she served as general counsel for Chevron Asia Pacific Exploration and Production Company. But taking such an assignment might be impossible for some women, resulting in limited advancement opportunities for them. “Expectations or requirements that look neutral may not be,” Francis says. “But is there a way that enables women to get valuable experience through other means so they can stay in the game?”

The blend of these skills is redefining leadership. I think a lot of the leadership books are emphasizing the competencies that were formerly labeled women’s traits.

Sheila Lirio Marcelo ’93

Byrne, for one, maintains that the Women in Leadership Index empowers investors who believe in the need for such questions. Their investments tied to the index could encourage changes in workplace policies and help foster a corporate culture that supports women’s advancement into leadership roles, thereby narrowing the gender gap at the highest levels of business. Although the index can include up to one hundred companies, only eighty-four qualify so far; Byrne is hoping the number will increase as more companies see that investors value gender-diverse leadership. Her own belief in its importance comes partly from thirty-five years as an investment banker, which has shown her that diversity leads to better-informed decisions and more desirable outcomes.

Yet the seeds for her work were planted before she began working on Wall Street. “Mount Holyoke was a tremendous education for me,” says Byrne, an economics major. “It was very expansive and broadening. It allowed me to ask the question ‘what if?’—what if we were to measure what matters by creating this index? And ‘what if’ is the most powerful question women can ask.”

In Brief: The Barclays Women in Leadership Index

Purpose:

To enable investors to send the message that they want to see more women in leadership positions at major companies.

Context:

As socially responsible investing continues to grow in popularity—appealing to those interested in making a positive impact through their investments—the Women in Leadership (WIL) Index has focused increasingly on specific areas such as alternative energy and fair labor practices. Investment products intended to promote gender-diverse leadership, while still limited, are part of this trend.

Peers:

Barclays’ WIL Index joins the Pax Ellevate Global Women’s Index Fund, a mutual fund launched last year that invests in companies worldwide where women are well-represented in management positions, and firms such as Morgan Stanley, which only includes companies with at least three women board members in its Parity Portfolio, aimed at wealthy clients.

Details:

The WIL Index is unique in that it is linked to the performance of exchange-traded notes—unsecured debt obligations issued to investors by Barclays Bank. Compared to other investment options, exchange-traded notes offer certain advantages, such as lower taxes, but they may also be riskier, because buyers can lose the money they have invested if the issuer goes bankrupt.

Performance:

When the WIL Index was established, there was no way to provide information to investors on its long-range performance. To give investors a broader picture, Barclays calculated how the index would have performed over the previous five years. While past performance isn’t a predictor of future performance, the calculations were promising: If it had been in existence, from 2009 through 2014 the WIL Index would have outperformed the S&P 500, considered the leading indicator for the US stock market.

—By Sonia Scherr

Sonia Scherr is a freelance writer based in New Hampshire.

This article appeared in the spring 2015 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

April 13, 2015

Leave a Reply