Trouble in Your Tank?: Ethanol Fuels More Problems Than It Solves

“What I find most puzzling is how little we, as a nation, seem to care about finding alternative solutions to the fuel mess.”

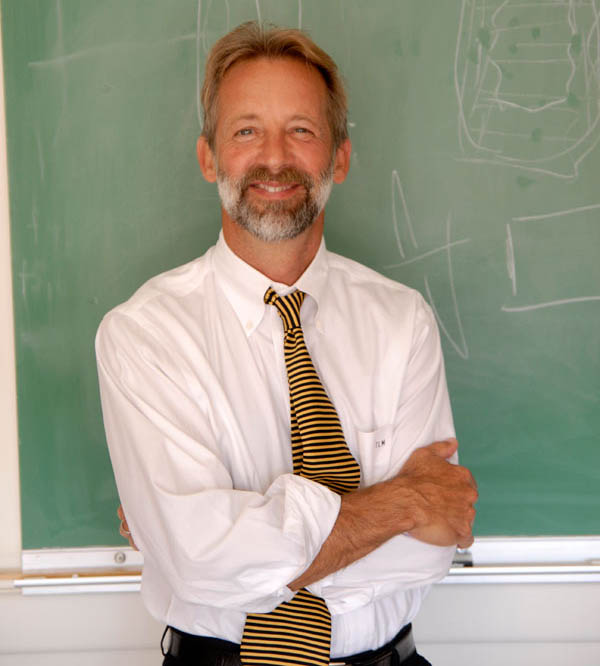

Thomas Millette, MHC associate professor of geography, explains why corn-based ethanol fuels cars and controversy. (Photo by Andrea Burns)

As summer hit the beautiful Mount holyoke campus, world energy and food markets were in a state of unprecedented turmoil. Lest you think I exaggerate, here are some sobering numbers. In 2003 the benchmark price of a barrel of crude was $34.79 (in 2007 us dollars). In 2006 the same barrel sold for $67.32. By mid-June the price hit $147 per barrel.* If I didn’t know better, I would think the time is ripe (sorry, I couldn’t resist) for biofuels.

Food prices have mirrored the rapid price increases in oil. Corn on the US commodities market sold for $2 a bushel from 2002 to 2006. In 2007 the price doubled. In mid-June the price shot past $6 a bushel. Over the last year, with an inflation rate below 4 percent, the price of eggs went up 35 percent, white bread went up 16 percent, and chicken went up 10 percent. Could these phenomena be related? It appears that the centerpiece of the US alternative energy policy, ethanol, has linked the global energy and food markets in a manner not seen before.

If you look at the menu of alternative energy, and in particular biofuel options, it would be useful to ponder why corn-based ethanol? How did ethanol become the highest-profile bullet in the US arsenal for reduced reliance on foreign oil, and for global-warming mitigation? Since fermentation of sugar into alcohol is one of the oldest chemical reactions mastered by humans, perhaps we are just comfortable with it. That the same basic process produces Clos saint-denis wine certainly gives me comfort. However, there is more going on here than my fantasy circling the Cote d’ or. There is a fantasy here, but this one is circling Capitol hill.

In all fairness, there are some compelling reasons to look at corn ethanol as a substitute for foreign oil. First, we’ve mastered the chemical process and packaged it into politician-friendly sound bites. Second, we have a superb infrastructure for producing corn with unmatched yields. Third, there is a well-cultivated notion that corn ethanol will reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Lest I forget, there is a fifty-one cents per gallon tax break for ethanol producers and federal subsidies to farmers who grow corn. Throw in the recent Congressional mandates to increase us ethanol production by 40 percent next year and 600 percent by 2022, and there appears to be a bright future in ethanol.

* P.S. It’s amazing what a couple of months will do to the price of oil. Since reaching a record of $147 a barrel in June, the price of light sweet crude retreated to $68 in late October. Although it’s hard not to take a bit of comfort in falling oil prices, what we are seeing is some short-term volatility due to dampening demand, not a trend. In July, I had dinner with some energy industry executives and they unanimously believed that crude prices would likely fall in the short-term due to high prices, but that the long-term trend was for prices to continue to rise due to increasing global demand. I think time will prove them correct. One of the unfortunate consequences of falling oil prices is the accompanying investment paralysis for alternative liquid fuels. –T.M.

So if you’re not an ethanol producer or a farmer, what’s the problem? To those of us who measure and count things, it looks like we are trading one problem for two. We clearly have supply and refining limitations (real or contrived) that are resulting in record prices for liquid fuels. If we continue to cultivate corn-based ethanol as the only solution, we will have two problems: record high prices for fuels and for food.

So if you’re not an ethanol producer or a farmer, what’s the problem? To those of us who measure and count things, it looks like we are trading one problem for two. We clearly have supply and refining limitations (real or contrived) that are resulting in record prices for liquid fuels. If we continue to cultivate corn-based ethanol as the only solution, we will have two problems: record high prices for fuels and for food.

Corn-based ethanol will never be an economically or ecologically viable substitute for gasoline, and continuing to develop this industry beyond a sustainable threshold will only drive global food prices to the same levels as oil.

If you can manage to bypass the mountain of compost on this topic shoveled around the blogosphere and on infotainment programs, the basic facts are fairly digestible. Let me share a few unvarnished facts and popular myths.

Fact: The production of corn-based ethanol is energy intensive. Considering tractors, combines, hydrocarbon-based fertilizers, fermentation, and ethanol’s lower energy density (56 percent lower than gasoline’s), the process consumes a great deal of fuel. The best calculation I can find comes from a group at Cornell, which estimates that it takes 1.29 gallons of gasoline to produce enough ethanol to replace a gallon of gasoline at the pump. It seems that producing corn-based ethanol is actually making us more dependent on foreign oil.

Fact: There is no nationwide distribution infrastructure for ethanol and no prospect for one anytime soon. Moving large quantities of ethanol the way we do gasoline is not possible for a variety of reasons. The most important reason is that it cannot be moved by pipeline from production facilities to markets, since ethanol absorbs water and impurities that are always present in these conveyances.

Fact: This year, 25 percent of all the corn produced in the United States will go to ethanol production, which will surpass the amount we export. All indications are that this percentage will continue to grow as the ethanol subsidy drives the development of more production facilities, further tightening grain supplies to the food market. For example, the rapid rise in corn prices (more than 300 percent since 2006) has resulted in farmers allocating more tillage to corn, reducing the supply of other grains and food commodities, causing their prices to rise also.

Now for a few popular myths:

Myth: The tightening corn supply is little more than a short-term productivity issue. Rising prices will generate investment and innovation that will raise productivity levels. This popular myth is generally spun: “When my grandfather worked this farm he got forty bushels of corn per acre. Last year I was getting 160 bushels, and someday we’ll get 300 bushels per acre.” Unfortunately, this well-worn tonic conveniently omits the fact that past productivity increases have been driven by having cheap oil as fuel for chemical fertilizers, pesticides, processing, and virtually every aspect of mechanized agriculture.

Myth: Weather is always the largest driver of grain supply and prices. The rapid price increases we currently see in grains are more a function of large-scale weather disruptions than of ethanol production. Well, historically this has been true, and to some extent weather will always be an important f

actor in grain prices. However, expanding ethanol production is one more tug on grain supply added to a collection of global factors, including large-scale crop-land conversion for urban, industrial, and commercial uses; and crop-land degradation due to rising salinity and dropping fertility.

Myth: Corn-based ethanol is a “green” fuel that will reduce global warming. In theory it could be, but not the way we do it now. As long as it takes 1.29 gallons of gasoline to produce ethanol with the energy equivalence of a gallon of gasoline, it’s hard to see this happening.

Cellulosic production of ethanol from forest and agricultural residues may move us closer to this objective, but breaking down cellulose into sugars is presently mired in technical challenges.

So where does this leave us? Clearly we have an economy and lifestyle that are at significant risk due to global demand for, supply of, and prices for liquid fuels. Globally, a food crisis is brewing, driven in part by the recent linkage of the food and energy markets. Although ethanol production at a glance seems attractive, when you look at the details, it doesn’t work. High fuel prices will probably do more good than harm in the short run by reducing demand. On the other hand, rising food prices create catastrophic misery and starvation. Unfortunately, the most vulnerable will bear the burden of this recent linkage of the food and energy markets.

Clearly, we have a national liquid-fuel problem. Unfortunately, our national ethanol policy is unlikely to solve it, and may create equally challenging problems for the food supply. What I find most puzzling is how little we, as a nation, seem to care about finding alternative solutions to the fuel mess we’ve seen coming down the pike since M. King Hubbert first published his theory of peak oil production in 1956.

—By Thomas Millette

Thomas Millette is MHC associate professor of geography. This article appeared in the fall 2008 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

This Web-exclusive content is offered in connection with the fall 2008 Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly magazine article “Trouble in Your Tank?: Ethanol Fuels More Problems Than It Solves” by Thomas Millette, MHC associate professor of geography. He selected these sites.

• A January, 2008, article from U.S. News & World Report discusses “The Pros and Cons of 8 Green Fuels.”

For each, the article notes: What is it?, What’s good about it?, What’s bad about it?, Where would it be most useful?, How much will it cost?, When’s it coming?, What’s taking so long?, Who’s doing it?, and Could it be a silver bullet?

The alternatives discussed are: corn ethanol, cellulosic ethanol, biodiesel, clean diesels, hybrids, plug-in hybrids, electric vehicles, and hydrogen/fuel cells.

• The National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Biomass Research Site

NREL is working to develop cost effective, environmentally friendly biomass conversion technologies to reduce our nation’s dependence on foreign oil, improve our air quality, and support rural economies. (Biomass is plant matter such as trees, grasses, agricultural crops or other biological material. It can be used as a solid fuel, or converted into liquid or gaseous forms, for the production of electric power, heat, chemicals, or fuels.)

• The US Department of Energy’s Alternative Fuels and Advanced Vehicles Data Center provides a wide range of information and resources to enable the use of alternative fuels, in addition to other petroleum-reduction options such as advanced vehicles, fuel blends, idle reduction, and fuel economy.

• The College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell University’s site on Biofuels and Renewable Energy Systems details research being done by university faculty in these areas: industrial biotechnology, green feedstocks, biogas processing, wind energy, sustainable land use for bioenergy, assessing biofuels at work in New York City, biofuels and renewable energy projects, and outreach, education and development.

• Cornell University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Bioenergy Feedstock Project site describes research on production of bioenergy feedstocks that was initiated in response to the need for information on planting and managing warm season perennial grasses and other crops for the emerging agricultural energy industry in New York State. An overarching goal of the project is to increase production of perennial grasses and legumes for use as bioenergy feedstock to support this alternative energy industry.

Move Over, Lara Croft: Not All the Women in Video Games Are Digital

Photo by Jude Mooney Photography

When you think of video games, you probably picture a geeky teenage boy camped out in a living room, chomping on potato chips while piling up points racing from one virtual level to the next. (You don’t imagine girls at a slumber party playing Super Mario Brothers, right?) The $42 billion-a-year worldwide video-game industry still reflects this stereotype, but career women in the field—such as Patricia Su Yin Kallusch ’93—may help change all that.

If you think video games are just kid stuff, think again. They’re the fastest-growing segment of the entertainment industry, and computer- and video-game sales are expected to surpass movie box-office revenues by the end of 2008. Grand Theft Auto IV, released in May, set a record for day-one sales in any entertainment sector.

Kallusch, who played video games casually while growing up, wondered how she would use her MHC studio art degree. Internships with a New York City sculptor and in the design department of DC Comics made her realize the broad possibilities of commercial art.

The video-game industry began to boom while Kallusch was in her mid-twenties. “Three-dimensional animation was really taking off,” she recalls, and 3-D artists originally interested in film careers took notice of the skyrocketing video-game sector. Armed with an MFA in computer animation, Kallusch built a career as an animator and video-game environment artist, then moved up the managerial ranks as though mastering levels in one of the games.

While an animator, she worked primarily as an environmental modeler for Electronic Arts, making the physical worlds video-game characters navigate. For example, she modeled the golf courses for the PlayStation 2 Tiger Woods PGA Tour game. After five years at Electronic Arts, the globe’s largest producer and publisher of video games, Kallusch was recruited by LucasArts to work on Star Wars: The Force Unleashed game, which came out in September.

At LucasArts she directed a team of thirty artists in varied disciplines. One role was to produce character art and animation. This included the production of visualization, creation, and animation of Darth Vader, his secret apprentice (pictured at left), and other characters (including Maris Brood, below, left). She also produced cinematics (brief movies) for the game and ran the project’s art outsourcing with teams at Industrial Light and Magic and Lucasfilm Animation in Singapore.

At LucasArts she directed a team of thirty artists in varied disciplines. One role was to produce character art and animation. This included the production of visualization, creation, and animation of Darth Vader, his secret apprentice (pictured at left), and other characters (including Maris Brood, below, left). She also produced cinematics (brief movies) for the game and ran the project’s art outsourcing with teams at Industrial Light and Magic and Lucasfilm Animation in Singapore.

Working with colleagues in design, marketing, and engineering, she managed art “assets” for the game. This could mean anything from driving the creation of marketing pieces to overseeing development of concept art used to inspire the designers and artists working on the game. “I was in charge of the art piece of the pie,” Kallusch summarizes. “As a producer and development director, coordination is key. I’ve been on afew projects [with] almost 200 people working together to create thegame. Defining and driving processes for art-asset creation isimportant because art is a key element of what enhances the experienceand makes players feel like they’re in the game.”

That sense of immersion reflects video games’ role as a new form of storytelling. Early games such as Donkey Kong and Pac-Man were all about scoring points. But some of today’s video games “involve more storyline, [so] the player can experience more emotion through the story, similar to how a person relates to a character in a film or a book,” Kallusch explains. “Different genres of games provide for different game-play experiences.” And recent game narratives emerge on the screen as fingers furiously tap controllers, with the story evolving differently for each player. “You’re actually creating an experience,” Kallusch says of games like Star Wars: The Force Unleashed and Grand Theft Auto. “Video games are a growing part of the future of the entertainment industry, and they are more and more about character,story, and emotions.”

Where Are the Women?

Where Are the Women?

This spring Kallusch returned to work for Electronic Arts, where she is doing the same tasks as at LucasArts, only on a much higher level. Currently she is in charge of a team of seventeen artists, only one of whom is a woman. “Being able to go toe-to-toe with other artists, regardless of gender,” was part of the industry’s appeal to Kallusch.

There are still many more “Lara Crofts”—female video-game characters— than actual women creating the games; Kallusch is among the few women managers. “Women probably think it is a bunch of nerdy guys … [but the industry] lends itself to so many jobs women may be interested in,” she notes, as if eager for female colleagues.

Would the presence of more women change the industry? Kallusch notes that customer demand drives video-game content, with men ages eighteen to thirty as the prime targets of video-game marketing. If that audience wants a game where women are busty and violent crime runs rampant, games will reflect that. Kallusch believes that the nature of the product will change only when women find a place in the industry and get more into gaming as entertainment.

Things are already starting to shift. According to the Entertainment Software Association, 38 percent of gamers are female, and they spend an average of 7.4 hours each week playing video games. Kallusch mentions that while the chances are slim of finding a woman in her thirties who is really into games like Grand Theft Auto, the social nature of other games may begin to build a new female consumer base. Socially oriented role-playing games such as The Sims series (which lets players simulate day-to-day activities such as eating, sleeping, and working, and control characters’ destinies) are popular with women. According to eMarketer research, females also prefer “casual games,” such as computer versions of board, card, and word games, rather than the battle games favored by males.

Although the video-game industry is still male-centered and male-dominated, Kallusch says anything can change if women infiltrate the animation floors and other parts of the business. She notes, “I didn’t see any ‘no girls allowed’ signs when I came in here.”

—By Caitlin Healey ’09

Caitlin Healey ’09 is an English major who is considering a future as a gamer. This article appeared in the fall 2008 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

Learn More

This Web-exclusive content is offered in connection with the fall 2008 Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly magazine article “Move Over, Lara Croft: Not All the Women in Video Games Are Digital,” by Caitlin Healey ’09.

Women and Videogames

• According to the Entertainment Software Association, 38 pe

rcent of gamers are female, and they spend an average of 7.4 hours per week playing video games.

• GIRL (Gamers in Real Life) is a scholarship program created by Sony Online Entertainment to attract more young women to careers in game development.

• Twelve percent of those employed in the videogame industry are female, according to the International Game Developers Association. (Women comprised 46 percent of the total U.S. workforce in 2007.)

• Women in Games International (WIGI) — This nonprofit organization was founded to include and advance the position of women in the game industry.

• A 2007 survey by eMarketer found that a slightly higher percentage of women than men use the Internet in general, but that “females, especially adult women, are more likely to use the Internet to get things done, rather than to have fun.”

• In a 2006 Nielsen Entertainment study, “women make up nearly two-thirds of all online gamers, [but] men still outnumber women in the overall video game universe by more than two to one.”

• Preview the New Star Wars Game

Check out the Star Wars: The Force Unleashed videogame at its official LucasArts Web site.

Nancy Philippine, a former manager of Pat’s at Electronic Arts (world’s largest producer and publisher of video games), talks about Pat Kallusch and the video game industry

How to Succeed in the Industry: I had the chance to follow closely Pat’s career at Electronic Arts (EA) from the time she started as an intern in the art department to now as an art development director. Pat’s skills and her desire to deliver the highest quality of work were appreciated from day one and are what allowed her to progress the way she did.

The role of an artist in the video game industry requires a different mindset than in other industries. You need the talent, but you also need to understand the technical restrictions. It has to be beautiful, but it also needs to fit in as little memory as can be. Using a 3-D application like Maya or Softimage can be a challenge for 2-D artists, but making these models migrate to the video game consoles is the next step above in complexity.

Pat belonged to this elite of artists who could work closely with engineers and translate the technical specifications to top-notch models and splendid textures, which complied with the requirements. (Think golf courses: lots of grass and trees but it also needs to look real and transport the player to golf courses he has seen on TV. Not easy!)

You also have to be well-organized. All pieces of your work have to be stored in specific locations and follow naming conventions. Why? First, somebody else might be using the same piece. Then, all game assets are recreated from bottom-up for each version. Complex scripts go fetch everything and work their magic to convert, combine, and compress all the data to their final format. If the script chokes because it does not find a texture or any other piece, you might be impacting the work of 100 people or more for the next day. You don’t want to do this too often.

Pat always had a lot of ownership for her work. She would be very meticulous and understand her place in the big picture. When you have 20 to 50 artists working on the content of one game, you don’t want to have to run behind each of them to make sure things are done right. Pat understood that and progressively started to monitor that process and supervise more junior artists and train them to follow the processes and pay attention to details. Not always easy for “right brains.”

As she got to work closely with the “left-brain” engineers, Pat got a passion for figuring out the pipelines with them. Optimizing the work is key on games. She really helped a lot on that matter.

Things evolve quickly in the industry. You have to be able to adapt and accept the changes. One aspect that was really tough for the art team was the fact that the more content you needed, the more artists were needed to meet the deadlines and the higher the cost went. To work around that, outsourcing became very popular. It had a lot of positives but it also meant a change of role for the internal team: managing the external team and fixing the issues that might have occurred from distant communication. Not easy to pilot this remotely. Another key role that Pat covered very successfully!

From there, the evolution is obvious. Pat has all the experience and profile to get to the next step of managing a team of artists, being responsible for their schedule, the processes they will follow, and the communication with the production team and the engineering team.

All of this understates the hard work and the long hours spent to meet tight deadlines. The industry is season-driven. You cannot miss your release date without major financial consequences. Crunch time is a reality but it is balanced with more flexibility in your day-to-day schedule. Core hours are a necessity to the collaborative work but as long as you deliver your part, you gain trust and freedom. It’s as tough for men or women; we are all on the same boat.

On being female in a male-dominated industry: Mainly it depends on the game you are working on. I was lucky enough to work on quite a variety, from shooters to racing games to golf games to the Sims. The Sims team included a lot of women in production and design—very unusual! All the other games were more targeting core players and had mostly a male staff, except for the art team. It’s starting to change now that girls are getting to play more games as well.

The goals are well-set and if you are self-driven, there is no reason for you not to succeed.

One of the important factors to growth is to find some good mentors. I was lucky to have many along the way who helped me through what felt like a natural progression. I’m sure Pat can relate to this as well.

On changes in the video game industry: It is challenging, evolving constantly, and most of all it regroups a fantastic set of people. Every time I thought I could finally rest, a new platform would come, changing the rules, asking us to experiment with new approaches not only on the technology but also on the project management.

The early teams (15 years ago) were made up of a couple of engineers. Then you had 5-10 engineers and 1 or 2 artists. Then you started seeing 15-20 engineers and 5 level designers and 15-20 artists and now it’s more 30-35 engineers and 10 level designers and 40-50 artists. It’s quite a reversed situation. And from day one, getting the right brain to meet the left brain has fascinated me.

Light Motifs – Marcia Birken’s Images Meld Math and Art

Patterns are important to Marcia Katz Birken ’71. As a mathematics professor at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) for nearly three decades, Birken taught about the elegant patterns numbers make. But a nature tour of Yellowstone National Park in 2005 sent her love of patterns in a new direction. “I was looking at the same things everyone else was, but I saw different things. They’d see flowers; I’d see rotational patterns in the petals. They’d see a landscape; I’d see patterns repeated in the meanders of the river. They’d see birds; I’d see how the feathers grew.” (Birken Photo: Leichtner Studios)

That moment of revelation brought together her love of the natural world and the mathematical world. Now retired from RIT, she pursues these merged interests through a third one, photography. Joined by husband Eric, Birken and her trusty Canon digital have camped across Botswana, explored Chilean Patagonia, and sailed to Antarctica on the icebreaker The Endeavor.

Wherever the site and whatever the sights, Birken finds patterns—“from the regular striping of zebras to the random scattering of wildflowers in a meadow; from mountains reflected exactly in calm waters to mangrove roots mirrored with distortion in swampy ripples; from the regular patterns of symmetry to the rough and jagged patterns of fractals; from number series in math to a series of birds in flight.”

Peering through a camera, Birken saw fractal patterns in Antarctic icebergs. She found Fibonacci sequences (a specific kind of repeating pattern) in the spirals formed by bracts of pinecones and the central disks of composite flowers, such as daisies. “I found patterns in nature that I had been describing mathematically,” she recalls. This realization bloomed into a new book, cowritten with professor/poet Anne C. Coon. Discovering Patterns in Mathematics and Poetry uses Birken’s nature photos to illustrate mathematical concepts, such as the Golden Mean, logarithmic spirals, and four types of symmetry.

Combining the scientific and the artistic isn’t new to Birken. “My whole career life has been based on what I learned at MHC. I majored in math and minored in religion. That [combination] seemed completely logical because I was educated to see everything in the world as connected.”

She and Eric (a physician with a flexible schedule) decide “quite spontaneously” when and where to travel, mostly joining small nature-travel groups. Their adventures have already included South Africa, Ecuador, Iceland, Israel, Britain, China, Costa Rica, and most recently, New Zealand. Visits to Yosemite and Glacier National Parks are on the horizon.

Although Birken’s photos are sold on her Web site and at occasional shows near her home, she says she’s “having too much fun [traveling] to organize the business end. Our kids are settled, so it’s easy to pick up and go. And I want to go everywhere!”

Learn More

This Web-exclusive content is offered in connection with the fall 2008 Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly magazine article “Light Motifs: Marcia Birken’s Images Meld Math and Art” by Emily Harrison Weir.

This Web-exclusive content is offered in connection with the fall 2008 Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly magazine article “Light Motifs: Marcia Birken’s Images Meld Math and Art” by Emily Harrison Weir.

Photos and explanations by Marcia Katz Birken ’71

FIBONACCI NUMBERS & GOLDEN SPIRALS

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, . . .

This list of numbers is the famous Fibonacci Sequence (or Fibonacci Numbers), named after the 12th century Italian mathematician, Leonardo of Pisa, known colloquially as Fibonacci or “son of Bonacci.” After the first two 1’s, each number is the sum of the two previous numbers (2 = 1 + 1; 3 = 1 + 2; 5 = 2 + 3; etc.). Fibonacci Numbers are intriguing, not only because of their mathematical pattern, but also because this particular sequence is closely linked to growth in nature. The pattern in which leaves occur on a stem, the number of petals or petal-like parts on some wildflowers, and the arrangement in the packing of seeds are all closely linked to Fibonacci Numbers. The daisy is an example of a composite flower, made up of disc florets in the center and ray florets (or petals) on the outside. The disc florets are arranged in clockwise and counterclockwise spirals. The numbers of spirals in each direction are consecutive Fibonacci Numbers. This relationship is echoed in spirals found in pinecones, pineapples, ginger plants, artichokes, and other plants. The spirals themselves are Golden Spirals, based on the Golden Ratio, whose exact value is approximately [1.61803. . .]. The ratio can be found by taking the limit of consecutive Fibonacci Numbers. This is the spiral of equiangular growth and is also displayed in the nautilus and other shells, in the seeds of sunflowers, and the horns of many animals.

This daisy, from Adirondack State Park, NY, was shot and cropped to emphasize the spirals appearing in the central disc florets. On the second and third photos, I have traced out the 21 clockwise and 34 counterclockwise spirals. 21 and 34 are consecutive Fibonacci Numbers. The spirals are Golden Spirals. There is also rotational symmetry in the petals or ray florets of the daisy (see SYMMETRY below).

The bracts of the red ginger plant from Costa Rica are also arranged in two sets of Golden Spirals. The numbers of clockwise and counterclockwise spirals are consecutive Fibonacci Numbers.

The unfurled spiral of this fiddlehead fern from Costa Rica is not a Golden Spiral. When tightly wound, it resembles an Archimedes’ Spiral and as it unfurls it looks more like a Hyperbolic Spiral.

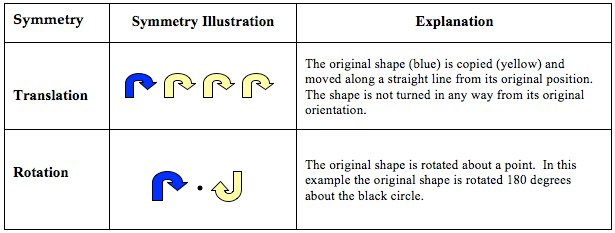

SYMMETRY

Mathematicians define four types of symmetry, as shown in this table:

Symmetry in nature may occur in natural growth patterns, such as the reflection pattern of butterfly wings, translation pattern of leaves, or rotation pattern of flower petals. Symmetry may also be found serendipitously in fleeting moments of birds in flight or through camera angles that show translation or reflection.

This Antarctic landscape shows exact reflection symmetry in a rare moment of still ocean waters.

A mangrove swamp in the Galapagos Islands shows distorted reflection symmetry as our slow-moving boat creates gentle ripples in the water.

Scarlet macaws fly in formation at dusk just outside the Carara Biological Reserve in Costa Rica. Their heads, body positions, and tails mimic translation symmetry, while their wings mimic reflection symmetry.

Black-faced ibis fly over Laguna Nimez Wildlife Sanctuary in Patagonian Argentina. Their heads and bodies mimic translation symmetry, while their wings mimic reflection symmetry.

When shot from a certain angle, this s

tand of large tree ferns in Costa Rica shows reflection symmetry.

Each branch of the fish tail palm of Costa Rica exhibits translation and glide translation symmetries, while corresponding leaves exhibit reflection symmetry.

This grove of aspens in Snowmass, Colorado, shows translation and glide translation symmetries from this camera angle.

Many mathematical concepts appear in this shot of fritillary butterflies on a composite flower in Adirondack State Park, NY. The butterflies’ wings exhibit exact reflection symmetry of their intricate pattern, while the petals of the coneflower exhibit rotational symmetry. The disc florets of the flower form two sets of Golden Spirals. The numbers of spirals in each set are consecutive Fibonacci Numbers.

SPOTS AND STRIPES

How did the leopard, cheetah, or giraffe get their spots? Why do the tiger and zebra have stripes instead of spots? It is all part of the complicated topic of morphogenesis—an aspect of developmental biology dealing with the formation of an organism and its parts. Mathematicians have proposed models of spot/stripe patterning based on the work in the 1950’s by the British mathematician, Alan Turing. Turing showed that while diffusion is usually a process that creates more uniformity, it may also destabilize a chemical system and produce patterning instead. Turing’s Reaction-Diffusion Equations have been used to develop models of different skin patterning caused by the diffusion of chemicals and their reactions in embryonic cells.

This cropping of two Burchell’s zebras feeding in the Okavango Delta of Botswana emphasizes their striping pattern—a pattern unique in every animal.

Similarly, the spotted pattern of a cheetah found in the Savuti Region of Botswana stands out in this close-up photo. Also noticeable are the rings at the end of the tail where the spots have morphed into stripes.

FRACTALS

A fractal image is one in which instances of either the entire work, or selected pieces of the work, are repeated. Perhaps each repetition is an exact replica of the original piece, or, more likely, the repetition just approximates the original. For instance, a single frond of a fern is a miniature version of the entire plant, much like a single floweret of broccoli resembles the entire head. From a mathematical point of view:

A fractal is a mathematical object, such as a curve, that displays exact or approximate self-similarity on different scales. The image of a fractal is frequently obtained from a recursive or iterative formula and when magnified, the resulting detail looks surprisingly similar to the original object.

One fractal, the Koch Snowflake, is constructed by iteratively removing one third of each side of an equilateral triangle. The portion that is removed is replaced by another equilateral triangle whose side is 1/3 the length of the previous iteration.

Many images in nature exhibit qualities similar to mathematical fractals.

The rocks on a beach in Olympic National Park, Washington, form a fractal-like pattern. If we zoomed in on a small part of the rocky beach it would resemble the entire beach.

Each part of the dandelion head, photographed in Iceland, resembles the entire head.

Zooming in on any portion of this Antarctic iceberg would produce a pattern similar to the overall pattern of the iceberg. Also the “fractured” outer edge of the berg has the jagged pattern similar to the fractal edge of a famous Koch Snowflake.

This close-up of another Antarctic iceberg shows the bubbles forming a fractal-like pattern.

Minerva Terrace, an extinct geyser in Yellowstone National Park, appears fractal-like in the white travertine steps and layers formed by mineral run-off. The same step-like pattern can be seen in the cyanobacteria mat formed from runoff of an active geyser in Yellowstone.

Alberto’s ‘Daughters’—MHC Bonds Buoy Professor Through Troubled Times

Alberto Sandoval-Sánchez with his “daughters” Krysia Villón ’96 (left) and Milagros “Millie” Cruz ’87 (Photo by Ben Barnhart)

Professor of Spanish Alberto Sandoval-Sánchez remembers his fortieth birthday party in 1994 as a death-taunting celebration. No one present thought the guest of honor, even if he was lucky, would survive until the millennium. He was gaunt to the point of wasting, and suffering advanced AIDS symptoms, including the loss of an eye. “It was a farewell to Alberto. But then, Alberto never died,” recalled Sandoval-Sánchez during a recent interview in his College Street apartment about a mile south of campus. He still refers to the 1990s as “the time I was dead.”

A long-term survivor of AIDS, Sandoval-Sánchez remains a vibrant and active part of academic life both at Mount Holyoke and in his fields of literature, Latina theater, Latino and “queer” identity, and monsters as literary constructs. Sustained by luck, patience, humor, and a powerful will to survive, Sandoval-Sánchez has a support network that is deep in the commitment his friends feel to him, and wide in terms of its sheer size. He cultivates dozens of mutually caring relationships, many of which grew out of his passions as a scholar. His health is now stable, but he is unable to teach courses.

Among those who delight in Sandoval-Sánchez’s presence on the planet is a group of women—many of whom don’t know each other—who identify themselves as “Alberto’s daughters.” They are students he bonded with in the classroom and through La Unidad, a Latina students’ organization he has been involved with as an adviser since he came to Mount Holyoke in 1983.

For some—who were struggling to claim their ethnic identities while mediating tensions between the privileges of an elite liberal arts college and socioeconomic backgrounds that often made them feel out of place—Sandoval-Sánchez was a welcome father figure. A number of students took to calling him “Papi” while getting to know him and his life partner, New York City architect John R. Schwartz, as mentors.

As his health regularly veered into precarious peril during the 1990s, and more recently through the soul-wrenching calamity of Schwartz’s sudden death of a heart attack in 2003, Alberto’s “daughters” rallied around him. They reciprocated his paternal support with filial love. What started as humorous and slightly ironic appellations evolved into profound and durable relationships.

Milagros “Millie” Cruz ’87 (at right in photo), a Hartford immigration attorney, was a first-year student the year Sandoval-Sánchez arrived at Mount Holyoke. He not only turned her on to the golden age of Spanish literature, which became one of Cruz’s majors, but he and Schwartz became her emotional pillars. Toward the end of her first year, Cruz’s brother, a Vietnam veteran and intravenous drug user, contracted AIDS and died.

Cruz remembers sitting at the bar at Woodbridges restaurant and finding Sandoval-Sánchez there. “He would be writing on his napkin, always writing any thought that came into his mind so he could use it later,” said Cruz. “We would chat literature, life, whatever.” As the relationship evolved, Sandoval-Sánchez and then Schwartz “helped mold my thinking and my conduct, not just intellectually but morally as well,” said Cruz, “Alberto and John helped raise me.”

She was “devastated” to learn of Sandoval-Sánchez’s diagnosis during her first year of law school. She knew the expected trajectory of AIDS, having watched her brother’s decline. And she knew what she calls “the intimacy of the illness,” as the patient loses independence. Cruz was there to drive Sandoval-Sánchez to New York, through a blinding snowstorm, on the day Schwartz died, and she stayed with him that week as he adjusted to the most painful trauma of his life.

Cruz is still one of many admirers who monitor Sandoval-Sánchez’s well-being. She calls South Hadley a “wonderful womb” where her teacher gets emotional sustenance from friends and colleagues. But, Cruz adds, “his support network goes beyond just the people who are around him physically … he has a far-reaching spiritual network. We keep him in our prayers, we send him our love, and when he’s not feeling well, we make sure to send him our energy.”

Meredith E. Field FP’96, a nontraditional-age student who is actually nine months older than Sandoval-Sánchez, is also part of the international “Alberto’s daughters” coterie. An analyst with the Center for Disabilities and Development at the University of Iowa, Field became Sandoval-Sánchez’s research and editorial assistant after taking his course on US Latino literature in 1995. “It was a critical class for me,” said Field, “I learned how to read in a different way—he called it ‘reading backwards’ … it was incredibly engaging.”

The next term she wrote “Imagining Alberto,” an article in which she related that from the moment she met him she started to fear losing him. There was a sense “that he was on the edge of a cliff,” said Field. “Once or twice a semester he would become very ill … he was so close to the edge.” Last Christmas they spent two days in Sandoval-Sánchez’s apartment working on a manuscript. “We just went back into writer/editor mode,” said Field. “It was a wonderful reconnecting.”

In addition to essays and plays, Sandoval-Sánchez has published several books since his diagnosis, including José Can You See? (1999), about Latinos on and off Broadway.

Krysia Villón ’96 (at left in photo), Alida Montanez-Salas ’89, Bibi Rahamatulla-Hayakawa ’86, Daniela A. Montecinos-Loubon CG’85, and Marcia R. Webb ’87 are all alumnae who view Sandoval-Sánchez as a fatherly figure. “I think Alberto and I were meant to cross paths and to be part of each other’s lives,” said Hayakawa, a Guyanese-American who is now a paralegal specialist in the major-crimes unit of the US attorney’s office in the Southern District of New York. Villón, a poet who works for the Mount Holyoke Alumnae Association, said Sandoval-Sánchez is one of the few people with whom she shares her works in progress. Villón, whose father is Peruvian, thinks of Sandoval-Sánchez more as an uncle, but she understands the daughter analogy. “There are many generations of us,” she said.

—By Eric Goldscheider

Eric Goldscheider is a freelance writer based in Amherst. This article appeared in the fall 2008 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

Learn More About Alberto Sandoval-Sánchez

This Web-exclusive content is offered in connection with the fall 2008 Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly magazine article “Alberto’s ‘Daughters’: MHC Bonds Buoy Professor Through Troubled Times” by Eric Goldscheider

Books by Sandoval-Sánchez

• Puro Teatro, A Latina Anthology, by Alberto Sandoval-Sánchez and Nancy Saporta Sternbach (University of Arizona Press, 1999)

• Stages of Life: Transcultural Performance

and Identity in U.S. Latina Theater by Alberto Sandoval-Sánchez and Nancy Saporta Sternbach (University of Arizona Press, 2001)

• José, Can You See?: Latinos On and Off Broadway. (University of Wisconsin Press, 1999)

Articles About Sandoval-Sánchez

• A 1997 Alumnae Quarterly article by Meredith Field FP’96 about Sandoval-Sánchez, “Imagining Alberto”

• A 2007 MHC Web site article, also by Eric Goldscheider, “Alberto Sandoval-Sánchez Up Close and Personal”

Koch Snowflake

Koch Snowflake