MHC Moment: May 2012

May is filled with countless moments that make Mount Holyoke distinctive, from the laurel parade and the singing of “Bread and Roses” at Mary Lyon’s grave to the baccalaureate ceremony in Abbey Chapel and the canoe sing on Lower Lake.

May is filled with countless moments that make Mount Holyoke distinctive, from the laurel parade and the singing of “Bread and Roses” at Mary Lyon’s grave to the baccalaureate ceremony in Abbey Chapel and the canoe sing on Lower Lake.

I treasure each of these traditions and value the lifelong bond created among those who share in these collective experiences. However, one of my favorite Mount Holyoke moments this month came during our meeting of the Board of Trustees. The chair of the board, Mary Graham Davis ’65, and I have sought to have as much interaction as possible between board members and members of Mount Holyoke’s faculty, staff, and student body. Thus, plenary sessions at the heart of the meetings included presentations by faculty members in computer science, physics, and biology, along with poster presentations by students, and a further session, orchestrated by the Instructional Technology staff, showcasing the use of technology to enhance courses in the humanities and social sciences.

These presentations demonstrated the exceptional dedication of our faculty and staff to providing a learning environment in which each and every student is challenged to excel. This level of dedication sets Mount Holyoke apart, as was highlighted recently when the College had more professors recognized by the Princeton Review for teaching excellence than any other institution in the country. The honor came as no surprise to those of us who have the privilege of seeing the faculty and teaching staff in action on a daily basis. They not only seamlessly integrate their own scholarship and creativity into teaching, but they also invite students to engage in collaborate research from the moment they step onto Mount Holyoke’s campus. The result is a relationship that extends beyond the classroom—a relationship that shapes the next generation of women leaders through active participation and service as mentors and role models.

The spring 2012 report of the College Planning Committee, “Save, Simplify, and Redirect,” outlines Mount Holyoke’s plans to further strengthen our significant accomplishments in teaching and staff excellence by enhancing advising through first-year seminars and creating an infrastructure to implement strategies for connecting curriculum and career. In the process, the College will promote experiential learning, increase funding for internships, and bolster partnerships with alumnae. I am extremely excited, for apart from the traditions that lead to an intergenerational sisterhood that spans the globe, the moments that mean the most to me are those like the ones contained in the board plenaries. Such occasions offer the opportunity to celebrate our entire community’s commitment to academic excellence as the unyielding foundation of Mount Holyoke’s mission of using liberal learning for purposeful engagement in the world.

–President Pasquerella ’80

Music That Speaks for Itself

Zeb Bangash ’04 is Half of Pakistan’s Hottest Pop Duo

Mubarik Ali Khan, a top classical Indian music vocalist, showed little enthusiasm when Zeb Bangash ’04 was introduced to him as a possible student in 1999. However, after her first lesson—a test run taking Bangash through basic scales to gauge her voice and musical sense—his indifference melted. “From now on I have made you my daughter,” Khan said. “If you are willing to work hard, you can become a classical vocalist.”

Khan can spot talent, classical or otherwise. Today, Bangash is the vocalist, and her cousin Haniya Aslam is the guitarist, for what Newsweek called “one of Pakistan’s hottest pop duos.” Zeb and Haniya have Pakistani critics and musicians raving.

“Zeb has infused her classical training into a Pakistani version of soft-rock,” says Pakistani guitarist Foaad Nizam. “She and Haniya have brought the singer-song-writer tradition to Pakistan. I would compare them to Tracy Chapman.” Others have called their genre-busting music alternative, art folk, ethnic blues, world music, even easy listening.

Pakistan’s top weekly, The Friday Times, praised their debut album, Chup (Hush!). “This is the most influential mainstream production work out of Pakistan as yet. It has raised high the standards of songwriting and live recording in Pakistan,” according to the Times.

Although Zeb and Haniya avoid overt political references in their songs, they are revolutionary simply as female singer-song-writers performing in public. Both come from a modernizing urban middle-class background that provided few female role models in music or the professions. Fifteen years ago, women from their background were housewives or, at best, teachers and professors. Any musical training women received was Jane Austen-style “accomplishments.” And singer-songwriters—male or female—are rare in Pakistan, Bangash says.

And the women are Pathan singers at a time when Pathan culture is in a conservative free-fall. Five years ago, the then ultra-religious government of Pakistan’s majority Pathan North West Frontier province banned music in public places, incarcerated musicians, and tacitly condoned bomb attacks on music and video shops. In that context, the two make a statement just by singing in Pushto, the Pathan tongue. “You can’t suppress our songs, our culture, and centuries of tradition by imposing extremist views on society,” says Bangash.

The songs on their album reflect Pathan musical influences, but also those of Lebanese vocalist Fairuz, and others. One of the band’s biggest hits—Paimana Bitte (Bring the Flask)—adapts Fairuz’s “sultry, jazzy style to Pushto and Darri [Afghani Persian] folk.” This style is threaded throughout their album, with Bangash’s voice—perfectly pitched and accented by nuances and inflections—nimbly moving between or holding notes because of her Indian classical training. Aslam adds a heavier voice and guitar accompaniment. A changing group of musicians backs the duo on everything from sarod (a deep-toned stringed instrument) and drums to trumpet.

Bangash and Aslam understand one another well, musically and personally. The two have known each other since they were toddlers and are practically sisters. They live together in Bangash’s family home in suburban Lahore; both are single.

They have always been interested in music—Bangash recalls, “it has just felt right when I sang ever since I was a child,” and Aslam played classical Indian drums as a teenager—but these interests had been channeled into classical Indian music.

It was at college—Aslam studied at Smith College when Bangash was at Mount Holyoke—that they started practicing together. They performed informally and for student events at both colleges. They also started experimenting with Western music, and date their musical partnership to one winter break. The cousins were snooping around the Wilder Hall basement one day when they came across an abandoned bookstore-cumcafé. There, surrounded by spiderwebbed coffee mugs, dusty chairs, and bookshelves, Aslam brought her guitar, and, half joking, Bangash sang. The genesis of Chup, their album’s title song, was in that basement.

They kept practicing throughout college and continued in Pakistan, where Aslam started teaching anthropology at an art school and Bangash joined her brother’s business, importing massage chairs from Singapore. The duo’s sound gelled and improved, and in 2003 they uploaded two songs to the Internet for friends around the world. “Before we knew it, someone told us that our song [Chup] was playing in the local radio stations,” says Bangash.

While Paimana Bitte receives enormous feedback from Pathans who ask them to keep the Pathan folksong tradition alive, Zeb and Haniya’s impact is felt nationwide—far beyond the Pathan community.

All the other songs on their album are in Urdu, Pakistan’s national language, and their lyrics appeal to urban youth. For example:

All this listening, my

patience, is exhausted

Enough

We have talked a lot, now

it is time for love

You should know what is

in my heart

This longing, this sweet

longing, what is it?

This refrain resonates with Pakistanis who find it difficult to date or even meet in public in this conservative society.

In Pathan culture musicians may be repressed, but Pakistan’s mainstream is hungry for music. After launching their album in July 2008, the cousins toured the country for three months, performing weekends at a multitude of new venues, including at a puppet museum and on television talk shows. They are also expected to sign a distribution deal with a label in India, and to tour the US, UK, and Canada this August.

The press is particularly excited that, unlike other Pakistani singers, the cousins are fiercely independent. One example: dress. Other stars in their position wear Western-style jeans and tops. Zeb and Haniya perform in casual Pakistani attire, loose-fitting pajama pants and long shirts called kurtas.

“The way they came on stage spoke volumes about their confidence,” wrote a reviewer in Instep magazine about a recent concert. “Dressed simply in pants and plain kurtas … they looked dramatic on stage. Zeb and Haniya are not pop tarts, and they don’t need designer wear to boost their profile. Theirs is a music that speaks for itself.”

And it speaks to the young. A thirteen-year-old niece of mine saw the video of their song Aitebar (Trust), which is simply filmed with two dancers floating around in a dimly lit old house. It was, she said, “magical.” That is the same word Bangash uses to describe the evening she discovered the abandoned café in Wilder Hall basement, when she and Aslam first played together.

To hear the magic yourself, visit www.zebandhaniya.com.

—By Abid Shah

This article appeared in the winter 2009 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

A Closer Look: Paranoid Parents: Get a Grip!

When Christie Horn Barnes’s husband died suddenly of a stroke six years ago, she was left alone to parent two-year-old triplets and a daughter who was four. Panic set in.

“I was in shock,” the 1977 alumna recalls of her bereavement and the consequent hyper-attention she paid to protecting her children. “I worried about them crossing the street, playing with strange dogs—anything.”

She wasn’t alone.

Barnes for several years fed her hunger for safety by running a store that featured the safest children’s products she could find, including high chairs, jogging strollers, and educational games. In surveys she did of her customers, 75 percent admitted they, too, worried about absolutely everything.

“One woman came up with 225 things she worried about,” recalls Barnes. “And that’s what really got me going on The Paranoid Parents Guide.”

For three years, she called federal agencies, health-care professionals, and everyone else involved in children’s safety, and started to compile a database. What she found surprised her.

Forget about the shark attack or football concussion or tainted food or the horrors of plastic, she notes in the guide, published in September. Parents who want to find the middle ground between raising independent kids and being racked with worry need only focus on two things.

“If kids wear bicycle helmets and are buckled into car seats, it cuts down the death rate 90 percent,” she says. “Do these two things and there’s not a whole lot else to be afraid of.”

Is she kidding? Did she miss the story about the doubling in incidence of hideous, infectious diseases, or the exposé on school shootings in small towns? No, she did not, and that’s just the point.

“Busy parents base their worldview on what they see on the news,” Barnes says. But news and talk-show coverage of teen suicide, child kidnapping, and stranger danger are all aberrant events. “It’s not a good assessment of what’s in your world. It’s about sensation,” Barnes underscores.

Coupled with the marketing dogma that fear sells better than happiness, we are spoon-fed our worst nightmares about things we can’t control. “And folks are really bad at understanding that kind of risk,” Barnes says.

The Paranoid Parents Guide offers lots of facts and the tools to help moms and dads parent with common sense. Children are not kidnapped and killed in droves, as some reports would lead you to believe. In fact, the biggest killer in every age group is the car accident, hence her focus on seat belts.

Barnes’s research left her with enough material for a series of Paranoid Parents books. Her next two guides will focus on education—our schools are not bastions of illiteracy and violence, as some media would have you think, she says—and food.

Raising healthy, independent children is not easy, Barnes admits. But moms, dads, and kids would all breathe a sigh of relief if the parenting approach shifted from endless hovering to supervised risk taking.

“We’re seeing kids who are starting driver’s education who have never crossed a road by themselves,” she says, incredulously. “Your purpose as a parent is to prepare them for the world outside without you.”

Anyone for a midnight swim?

—By Mieke Bomann

FEELING PARANOID?

Check out www.paranoidparentsguide.com

Battling Bullying: What to Do When Push Comes to Shove

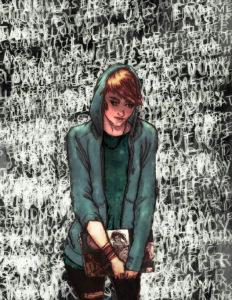

The story of Phoebe Prince, a fifteen-year-old student at South Hadley High School who took her own life last January after being bullied mercilessly by classmates, made national headlines. The Boston Globe ran a column titled “Untouchable Mean Girls,” and Phoebe’s photo was splashed on the cover of People. The case appeared on the evening news and was debated on the Dr. Phil and Today shows.

The story of Phoebe Prince, a fifteen-year-old student at South Hadley High School who took her own life last January after being bullied mercilessly by classmates, made national headlines. The Boston Globe ran a column titled “Untouchable Mean Girls,” and Phoebe’s photo was splashed on the cover of People. The case appeared on the evening news and was debated on the Dr. Phil and Today shows.

Massachusetts Northwestern District Attorney Elizabeth D. Scheibel ’77 took an aggressive stance with Prince’s bullies, handing down serious criminal charges including civil rights violation with bodily injury, which carries a maximum penalty of ten years in prison.

“It appears that Phoebe’s death on January 14 followed a tortuous day for her, in which she was subjected to verbal harassment and threatened physical abuse,” Scheibel said in March. “The events were not isolated, but the culmination of a nearly three-month campaign of verbally assaultive behavior and threats of physical harm.” Scheibel also charged the two male bullies with statutory rape because they were seventeen and eighteen, while Phoebe was under the age of consent.

Although Scheibel was not at liberty to discuss the ongoing case with me, she said that bullying is an issue her office has been working on for at least a decade. “A couple of years ago, we saw an increase in bullying between girls—increased aggression,” added Scheibel.

Bullying is serious

What happened to Prince was extreme, but many children and teens endure less serious harassment and taunting that can have a lifelong psychological impact.

South Hadley High had a history of bullying incidents before Prince’s case. A 2005 survey revealed that 30 percent of students said they’d been bullied in the past year. National research shows that as many as 25 percent of US students are bullied with some frequency.

Prince’s suicide has served as a wake-up call not just for South Hadley High, where an Anti-Bullying Task Force was formed soon after her death, but also for schools, administrators, and parents across the country. Prince’s case galvanized Massachusetts legislators to revive a decade-old anti-bullying bill (it passed last April), and it has inspired school districts from coast to coast to launch anti-bullying curricula.

“For too long, schools in general and organizations that work with kids have taken the perspective of, ‘Boys will be boys, and girls will be girls, and everyone goes through this,’’ says Christopher E. Overtree, director of The Psychological Services Center at UMass–Amherst.

But as a teacher or parent, it is vital to intervene.

Sabrina Vollers ’02 was bullied ruthlessly as a kid. “I was hit, spat on, called mean names, taunted, tricked and pranked, completely ostracized, even had my books and belongings peed on,” recounts Vollers. This occurred from fifth through eighth grades, and she didn’t escape the misery until she left for an all-girls’ boarding school for her freshman year of high school.

Vollers, like other alumnae I interviewed, remembers this harassment with startling specificity, even though it happened decades ago. She says she never could have survived those torturous years without the support of her parents. (Interestingly, they had both been bullied as children, too.)

“They were never like, ‘Why are you so unpopular?’ They were very sympathetic and always told me that, if I ever had to do anything in my defense, they would totally back me up,” she says. Her father always told her, “If anybody hits you, you hit them back.”

At one point, Vollers did just that, when a kid in English class called her a “fat pig” and drew a line from her forehead to her chin, cutting her with his pen in the process. “I was so upset that I punched him right in the face,” says Vollers. “The teacher said, ‘Oliver, go to the principal’s office right now and stay there until the end of the day.’” Vollers remembers this as one of the few times when a teacher was on her side.

Christina La Luna ’93 says that teachers at her Catholic elementary school in Pennsylvania only worsened her already miserable situation. During a vocabulary lesson, one teacher introduced the word lunatic. Because of her name, “From that point on, I was known as “La Lunatic,” she recounted. “It was very hurtful for that to dog me year after year.”

What teachers can do

Teachers should intercede when they witness bullying, but they often don’t, say bullying experts, mostly because they aren’t taught how to recognize and handle difficult social relationships.

“Teachers get little training in understanding social relationships,” says Susan Engel, a senior lecturer in psychology at Williams College. “They don’t know how to evaluate a kid who needs treatment” for bullying behavior.

In July, Engel and her colleague Marlene Sandstrom, a psychology professor at Williams College, wrote an op-ed piece for the New York Times, urging schools to go beyond quick-fix anti-bullying measures (such as a one-time assembly speaker) and instead invest in comprehensive training sessions in which teachers and administrators learn how complex children’s social interactions really are.

“Some bullies have a pathology underlying their bullying—they need special therapy,” says Engel, but the more common kind of bullies are otherwise nice kids. “If they came to your house with their parents, they’d seem like cute, normal kids. And they are, but they’ve gotten really off track.” These are the kinds of kids teachers can typically reach, says Engel.

Furthermore, students need to know which adults they’re supposed to report bullying incidences to, and that adult needs to be nonthreatening. “It’s amazing how many kids, when you ask them, say, ‘I wouldn’t know who to tell,’” says Sandstrom. “And then many teachers say, ‘Stop being a tattle-tale.’”

In Norway, where a series of bullying-related suicides in the early 1980s forced a national conversation about how to combat bullying, the government passed comprehensive anti-bullying legislation. In their op-ed, Engel and Sandstrom described that country’s efforts, which have been extremely effective. “There, everyone gets involved—teachers, janitors, and bus drivers are all trained to identify instances of bullying, and taught how to intervene. Teachers regularly talk to one another about how their students interact. Children in every grade participate in weekly classroom discussions about friendship and conflict.” During the first two years of these programs, bullying fell by half.

The man behind Norway’s initiatives is Dan Olweus, and his anti-bullying prevention program is considered one of the most effective in the world. Many US schools have already implemented it with great success.

Several years ago, D.A. Elizabeth Scheibel’s office invited bullying expert Rosalind Wiseman, author of Queen Bees and Wannabees, to present her Owning Up curriculum to interested area teachers and administrators. The program aims to get students to take responsibility for unethical behavior. Wiseman’s two-day workshop used a “train the trainers” approach—teachers returned to their schools to implement it. Scheibel’s office recently sent a staff person to become a master trainer in the Olweus program; this fall, the D.A.’s office will offer that program to district schools.

At Wahconah Regional High School in Massachusetts, history teacher Caitlin Harrigan Graham ’07 rarely sees bullying. She credits the school’s long-term investment in promoting a sense of community between students and faculty via an annual “Civility Day.” “Kids tell heart-felt stories. Teachers say things like, they used to have a lisp and were made fun of—and that’s why they became a teacher in the first place. This hits home with the kids,” says Graham. “One teacher spoke about being gay, and growing up at a time when it was not all right.”

The only time that Graham witnessed bullying at her school was last year, when she overheard a sophomore boy teasing a freshman girl who had had an abortion earlier in the year. “They were in study hall talking about a book they’d read in which this character had had an abortion. He said, ‘That’s you,’ and poked her. She looked upset,” recounts Graham, who immediately went over to remonstrate him. “He instantly said, ‘I’m really sorry Ms. Harrigan, I’m really sorry, Sarah,’” says Graham.

Improving the social climate through something like Civility Day is exactly what Overtree, the UMass–Amherst professor, does as a senior consultant for the Center for School Climate and Learning. “I think of my work not as anti-bullying but as pro-social work,” he says. “We try to stimulate a positive social climate that makes bullying stand out as a negative behavior.” He does this by first understanding what a school’s community norms are and then by forming student leadership teams. “Bullying happens in front of other kids. We need bystanders to step up,” he says.

In one Tennessee school that Overtree and his colleagues assessed, the main issue was that the students lacked empathy. Instead of having teachers give lectures on bullying, faculty and staff approached the dilemma creatively: they purchased hand looms and started a club where students made hats for newborn babies in the community as well as pediatric cancer patients at local hospitals. “It was just a little hat program, but it had a drastic change on the demeanor of the school,” he says. “Every student became engaged. Academically, things improved, too.” Overtree says this side benefit is common. “After a good climate-improvement process, you will see about an 11 percent improvement in academics.”

What parents can do

Sabrina Vollers ’02 remembers clearly how her mother calmed her down during the worst of her harassment. “When I came home from school crying, my mom used to tell me ‘Look, these people are nothing. They don’t mean anything in your life and you’ll soon be on to bigger, brighter, and better things. It won’t matter what happened in grade school.’” Her mom’s words have borne themselves out. Vollers, now getting her PhD in biochemistry, has a great circle of friends and is amused by one turn of events. Some of these very same bullies now want to “Friend” Vollers on Facebook. “I certainly wish them the best,” she says, “but I don’t want to be their Friends.”

Aside from emotional and moral support, parents can also play a crucial role by communicating with teachers and administrators. “Parents need to be on board with the bullying policy,” says Sandstrom, who suggests sharing the policy with parents at a mandatory PTA meeting. That way, they’ll know whom to talk to—a guidance counselor, the principal, a teacher, or all three—should their child become a bully or the victim of bullying.

But parents also need to teach their kids to respect others and appreciate their differences. Elizabeth Scheibel ’77, the D.A. in the Phoebe Prince case, says she never would have dreamt of talking to anyone the way the kids at South Hadley High allegedly spoke to Prince. “I don’t want to sound Pollyannaish, but I was raised in a home where we were taught manners, respect, and civility,” says Scheibel. “It wasn’t acceptable to talk about others in a negative way. It wasn’t tolerated, quite honestly.”

The new twist of cyberbullying

It used to be that bullying was more common among boys, but with the advent of Facebook, Twitter, and text messaging, bullying is now equally prevalent between both genders, says Overtree. Girls tend to be more proficient at what social scientists call “relational aggression”—teasing, malicious gossip, and verbal threats—all of which are facilitated by technology.

Boys, however, also use technology to harass their peers. Susan Vaughan-Fier ’94 is a teacher at a private high school in Minnesota, where several boys were suspended last year for sending harassing texts of a sexual nature to female classmates.

“The girls who reported it later wanted to recant,” says Vaughan-Fier, explaining that they were bullied again—by the same boys and by female peers—for having spoken out to their teachers. “But the text evidence was there.” This incident motivated the school to examine its sexual-harassment policy and to institute weeklong homeroom lessons on sexual harassment.

Barring your children from the Internet is not practical or necessary, says Gail Scanlon FP’94, who works in Mount Holyoke’s Library, Information, and Technology Services and who served on the Online Behavior Subcommittee of South Hadley High’s Anti- Bullying Task Force.

“It was important for me to help people understand that barring access to the Internet and social-networking sites is not the answer to eliminating bullying,” says Scanlon. Among her task force’s recommendations were free workshops for parents about online safety and privacy issues; a public service announcement student contest against cyberbullying; and mandating that each student receive at least two hours of training about cyberbullying each year.

Psychologist Susan Engel says that, while the Internet offers another venue for bullying, it hasn’t necessarily increased bullying. “Kids have always gossiped and done it away from adult eyes,” she says. “They used to do it at the park or in the woods or at the back of a soda fountain shop.”

It’s naïve to think that bullying can be prevented entirely. However, being pro-active—by teaching kids civility, creating community, and forging collaboration—can create an environment in which bullying becomes rare. When there’s a shared sense of responsibility, of working toward a common goal—remember the Tennessee students who made hats for pediatric cancer patients—kids are more likely to have empathy for one another.

Engel’s son’s school district has started a community garden. “It promotes community and a sense of shared responsibility, a sense of the common good,” she says. “Any school could do this. It’s just a matter of will.”

—By Hannah Wallace ’95

This article appeared in the fall 2010 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

Anti-bullying resources

Olweus Bullying Prevention Program

Olweus Bullying Prevention Program

(www.olweus.org) Dr. Dan Olweus is the pioneering bullying researcher whose anti-bullying initiatives were adopted by the Norwegian government and rolled out at public schools there in the early 1980s. (As a result, the incidence of bullying fell by half.) This site contains program materials, video archives, and up-to-date information on conferences and online seminars.

Stop Bullying Now

(stopbullyingnow.hrsa.gov), produced by the Health Resources and Services Administration, has sections targeted to both kids and adults. For adults, there are tip sheets, background on cyberbullying, and best practices in bullying prevention. For kids, the site has cartoon Webisodes illustrating common bullying scenarios (pictured below), tips on how to be a youth leader, and simple steps to take if you’re being bullied.

The Center for School Climate and Learning

The Center for School Climate and Learning

(www.necscl.org) This site has information and videos about the New Hampshire-based company’s services—which include student leadership training, Webinars for teachers and administrators, and SafeMeasures (a four-stage process that brings together teams of student and adult leaders to set goals, create action plans, and initiate projects that promote measurable school climate improvement). There is also a great page of resources that relate to school climate, bullying, respect, and safety.

Rosalind Wiseman: Creating Cultures of Dignity

(http://rosalindwiseman.com) The author and educator on children, teens, parenting, education, and social justice aims to help parents, educators, and young people successfully navigate the social challenges of young adulthood. Her blog posts cover topics such as “5 Ways to Prevent and Stop Cyberbullying” and “Why Are Our Girls So Angry?”

The Life of the Hands: Does Hands-On Work Mean Leaving Brainwork Behind?

So you think grad school’s difficult? Try lifting fifty-pound bags of flour; or climbing a ladder in the snow to work on electrical lines; or repeatedly cutting and gluing pieces of wood and leather to make a musical instrument. Sometimes the life of the hands is just as challenging as the life of the mind.

Cruz Ricker ’95

Cruz Ricker ’95

With a hardhat, drills, wires, and other apparatus, Claire “Cruz” Ricker ’95 gets downright dirty every day. She’s definitely not your average Mount Holyoke alumna. Ricker is a licensed journeyman electrician. When other alumnae hear this, they usually say, “How cool!” and ask for her card.

The route to her goal was not an easy one, though, and included far more years of training than for those in other, more white-collar, fields. Five years total, to be exact. Five years of working three jobs just to earn journeyman status—only to be laid off. “Most people who go to school for five years get called doctor when they finish,” she joked.

Working in a traditionally male-dominated field and taking in stride the culture that comes with it, Ricker is no joke. “There is an incredible amount of judgment and prejudgment of women on the job site. It’s a tough road for a woman,” said the Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, resident.

This tough road was not always a dream for Ricker, who majored in American history at MHC. She studied hard, but never found in college what she wanted to pursue in life.

To pay the bills after graduation, she worked in retail, at a nonprofit, and as an emergency medical technician. Then, in 2000, she answered an ad for a carpenter’s apprentice. Being an apprentice wasn’t easy, and the pay was pitiful. “My first year, I worked as an apprentice, an EMT, and for a friend in construction, just to make ends meet,” she said.

After being told she was good at electrical work, she switched from carpentry to seek an electrician’s license. But that wasn’t all glory, either. Although she has always been “out” about her sexual orientation with her crew, Ricker was victimized on a larger job when her hardhat was vandalized; someone wrote “fag bitch” on one side and “dyke” on the other.

“My father told me I should wear it that way,” she said, noting she never felt unsafe and that probably someone was upset that a woman was on the job. “You must advocate for yourself, but it’s a fine line. You have to be one of the boys, while never being one of the boys. I have managed to find a balance.”

But nothing beats being in the union, she added, where she has been since 2002. The benefits are amazing, including full health coverage while she’s unemployed. She also gets professional development opportunities such as classes at Wentworth Institute of Technology, where she earned a certificate in construction management.

“The union is a brotherhood … we have all the same skills,” said Ricker, adding, however, that sometimes “brotherhood” comes before “we all have the same skills.”

When she was laid off, Ricker was told a few times, “If we have a job where we need a woman, we’ll call you.” She said that is just one of the ways sexism is blatantly obvious. “Why ‘need a woman’? Why not just ‘need a job done’”? she asked.

Right now, she is on the union’s out-of-work list, along with 1,800 fellow electricians, and her priority is to get a job, any job. That’s not stopping her from considering her future, though.

“I was approached by another member to take on the state senator in my district, and I’m considering it. I’m also very interested in grad school,” she said, adding that she’d like to go into urban planning. “I’ve seen how [structures] get built and by whom, but now I want to know why and I want to be a part of it.”

When asked whether she feels her career is a cheat to her Mount Holyoke education, Ricker replied no. “I ask myself that sometimes, when I’m on a ladder in the snow … knowing I went to the best liberal arts college in the country … I don’t think I would have been able to stick with it, if I didn’t have the Mount Holyoke ‘cando’ attitude. Then I wonder, ‘Why can’t I translate that to my field?’”

Marga Hutcheson ’08

The hand-held instrument is small for the size of the melodies it produces, but it takes days of work to craft a single one. For Marga Hutcheson ’08, it is her life and her job. She makes concertinas, cousins to the accordion.

“My current job is pretty out of the ordinary,” said the Amherst, Massachusetts, resident. Hutcheson is the second-most- junior employee at The Button Box in Sunderland, Massachusetts. Although the business makes, sells, and repairs concertinas and accordions, she works “almost exclusively in constructing new instruments.”

Hutcheson’s days often look the same, and her hands definitely get a workout. “The work is quite repetitive and involves lots of cutting and gluing leather [to make the bellows], hammering, putting in springs, and sanding wood,” she said. “I use chisels, tweezers, hammers, electric sanders, and sometimes the drill press or band saw.”

Unorthodox as her job may be, she still manages to balance intellectually her MHC education with her blue-collar work, and feels her current job “is actually quite an appropriate next step after MHC. There certainly are times when I have to use my intellect quite a bit. I am always thinking about how I can make things more efficient, and occasionally I get to be inventive and figure out how to do something new.”

The young alum likens the repetitive nature of her work to meditation. “Having work where I often do not have to think allows me to reflect on the various mental states that arise, and to cultivate my ability to keep on returning my awareness to the handwork I am doing and to my breath … At Mount Holyoke, I studied religion, especially Buddhism … This experience has helped me turn what could have been a boring job into a fruitful, almost spiritual practice,” she said.

An environmental studies major at MHC, Hutcheson said she feels “grateful … to be working at a job that I feel is fairly good, from an ethical standpoint. I am working for a small, local company, making something that people hopefully will not just consume and throw into a landfill,” she said.

Hutcheson’s MHC friends are “generally pretty positive about the work I do and see its value,” but she admits she has felt “a bit inferior for not being in grad school or ‘knowing what to do’ with my life … I probably won’t be a concertina maker all of my life. I am grateful to have a job that uses different skills than those I was learning at Mount Holyoke, but that also has some continuity with what I was doing at MHC.”

Kirsten Baumgartner Stetler ’96

Carefully scraping the last bits of dough from her mixing bowl, Kirsten Baumgartner Stetler ’96 makes sure not a single chocolate chip goes to waste. It may be her 300th batch of cookie dough, but she wouldn’t trade baking for the world.

“There is … something soothing about repetitive work. When you get in a zone, you don’t have to think about what you’re doing anymore and your mind is clear; that’s really nice,” said the Vermont resident.

Stetler, who left Mount Holyoke midway through sophomore year for financial reasons, said, “I had a great experience at MHC, but it was too brief. I wish I could have stayed longer because I’m sure I would have benefited more.”

After leaving MHC, she first went home to Philadelphia to earn money to finish school. Her interest in photography blossomed, and Stetler finished her degree at the Art Institute of Boston (AIB).

“I decided to study photography because it was something I enjoyed doing, and I knew I needed to get my bachelor’s degree. I didn’t think much about a career path at that point because, after several years of trying to finish college, that felt like my career,” said Stetler.

After graduation, she took a job in the Student Services Office at AIB, and “ended up on a ‘cubicle career’ track … I never pursued a career in photography because it was very personal for me, and I didn’t want to lose my enthusiasm for it by making it my job,” she explained.

But something about cubicle life didn’t sit well with her. “I was feeling unhappy being in front of a computer all day, not doing anything creative, and I didn’t feel I was really helping anyone or contributing anything to the world. And spending half of your waking hours doing something you don’t enjoy is such a waste. I decided that if I had to work … I would rather spend that time doing something I enjoy,” she said.

Baking fit the bill. “I chose baking as a career because I have always enjoyed making bread, and working with yeast just fascinates me. As a living organism, it’s so interesting; there’s nothing else like it in cooking. I loved baking at home and wanted to learn more, to master it. Even though I’m done with school, there is still a ton more to learn about bread and yeast.”

So last year, she and her husband picked up, packed up, and moved to Vermont so that Stetler could enroll in a baking program at the New England Culinary Institute; she graduated earlier this year. After finishing an internship, the Vermont Cake Studio in Waterbury employed her as assistant pastry chef. So far, she loves it.

“Everyone I’ve told about my career change has been enthusiastic,” Stetler says, and some confide that their own secret ambition is to be a baker. Working for half her previous salary and at the bottom of the pay scale, since she’s new to the field, Stetler says she still makes a living and that the tradeoff is worth it for the enjoyment and the career possibilities baking provides.

“Definitely the hardest part of my job now is the physical labor, just being on my feet all day, lifting fifty-pound bags of flour, rolling out croissant dough for pastries that take all day to create. The good part, though, is that at the end of the day, you really feel like you’ve worked,” she said.

Her creativity and hard labor shine through when a customer wants a cake in the shape of something off the wall. “Sometimes I will discuss how the idea could be executed with my boss … Or I’ll look online for photos of what other people have done, or just Google ‘pterodactyl,’ so I know that I’m accurately representing the thing they want on the cake,” said Stetler. (Yes, she did design a pterodactyl cake.)

But just because she chose a career in the kitchen doesn’t mean her education went to waste. “I don’t think there’s a hands-on job that doesn’t involve the intellect, unless maybe you’re in a factory just pushing a button all day. Baking is a science; you have to understand how it works to be successful. If a recipe doesn’t come out right, you need to be able to figure out chemically what went wrong and how to fix it,” she said.

—By Susan Bushey Manning ’96

This article appeared in the fall 2010 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

IS YOUR COLLAR BLUE TOO?

Share how you work with your hands at alumnae.mtholyoke.edu/hands_on.