Catalyst for Change: Shirley Chisholm’s time in Congress, on campus and beyond

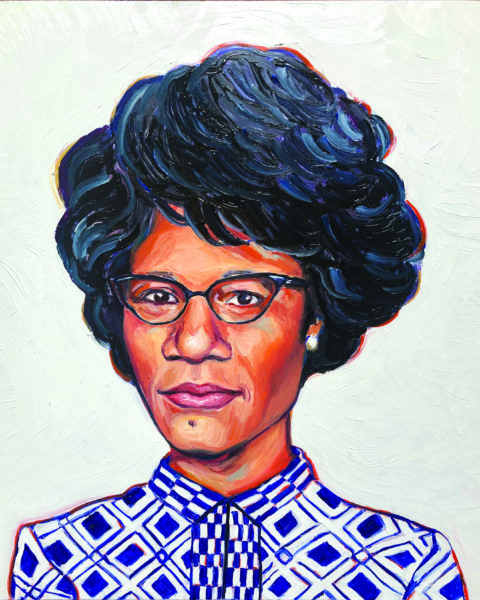

Portrait by TL Duryea ’94.

In late January 1972, a petite African American woman took center stage in the auditorium of the Concord Baptist Church School in Brooklyn, New York. The room and rafters were overflowing with press and several hundred supporters, and all eyes were on the 47-year-old woman in a black-and-white brocade suit. There was loud applause as Shirley Chisholm stepped up, grinning broadly, waving enthusiastically and nodding appreciatively to the crowd.

“I stand before you today as a candidate for the Democratic nomination for the presidency of the United States of America,” she said, from under the glare of the lights and behind a cluster of microphones. “I am not the candidate of black America, although I am black and proud. I am not the candidate of the women’s movement of this country, although I am a woman and I’m equally proud of that. I am not the candidate of any political bosses or fat cats or special interests. … I am the candidate of the people of America.”

On that historic day, Chisholm became the first African American to seek the nomination of a major party for the presidency and the first woman to pursue the Democratic ticket. Her voice was strong, with a hint of a West Indian accent; her diction precise; and her speech had the cadence of a preacher. Video footage of the speech shows the room exploding with applause and camera flashes flaring off of her glasses as she thundered on. Chisholm talked about the “three evils” — as Martin Luther King Jr. had called them — of excessive materialism, racism and militarism, as well as sexism, environmental degradation, campaign finance reform, and in-fighting in Washington, D.C.

Shirley Chisholm speaking to delegates at the Democratic National Convention July 12, 1972, in Miami Beach, Florida. Photo by Warren K. Leffler, Library of Congress.

Fourteen years after her death, Chisholm is still very much a public figure. In July the first phase of a 400-acre New York State Park named in honor of Chisholm opened in Brooklyn, New York. A public monument to Chisholm is also being planned for the entrance of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, and a feature film is in the works. Many recent candidates for Congress, and for the 2020 presidential nomination, have evoked Chisholm in some way. Tattoos, T-shirts and coffee mugs bear her image, and social media is abuzz with her catchphrases, such as, “If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.” Chisholm has been embraced as a symbol of what can be achieved despite poor odds and as a role model for speaking up for justice.

For many Mount Holyoke alumnae the resurgence in Chisholm’s popularity is a reminder of their very personal connection to the trailblazer, who gave the 1981 commencement speech and later taught at the College. By the time she arrived on campus in 1983 she was legendary, but the Shirley Chisholm who greeted Mount Holyoke students was an engaging teacher, an avid listener and a generous mentor.

This is fighting Shirley Chisholm

Chisholm thanking delegates at the Democratic National Convention, July 12, 1972, in Miami Beach, Florida. Photo by Thomas J. O’Halloran, Library of Congress.

Shirley Chisholm was born in Brooklyn in 1924, the daughter of a domestic worker/seamstress and a factory worker, both immigrants from the Caribbean. She spent most of her life in Brooklyn except for several years during the Great Depression when she lived in Barbados with her grandmother. Chisholm graduated from Brooklyn College and earned a master’s degree in education from Columbia University. Later she was a teacher, childcare center director and educational consultant for New York City’s Division of Day Care. From 1965 to 1968, Chisholm served in the New York state legislature, only the second African American to have held that position. During that time she fought hard for her constituents, pushing back against racial prejudice, gender inequality and economic injustice. She sponsored six bills, three of which became law.

Chisholm bucked convention again when she announced that she planned to run for Congress to represent New York’s newly formed 12th Congressional District in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. She was encouraged by peers and neighbors, who recognized the strength and conviction of her leadership.

When a woman knocked on the door of Chisholm’s brownstone and handed her an envelope filled with $9.62 in change, collected from other women in the neighborhood who wanted her to run, Chisholm knew she held in her hands her first campaign contribution. She closed the door and sat down, still holding the envelope, and cried. That moving gesture, which she told Ebony magazine about later, drove her to run. She brought on an all-female campaign staff to help.

After winning the primary bid to be the Democratic nominee, Chisholm challenged Republican-backed liberal James Farmer in the general election. Both were black, and Farmer had gained fame for his civil rights work, so he focused his campaign on gender, saying that Brooklyn needed a man to represent its interests in Congress. In an interview in 2002 Chisholm reflected on that time: “James Farmer laughed when I made the bid to go to Congress. He said, ‘She’s a little school teacher. I mean, look at her. She’s tiny, she’s frail, she can’t do that work.’” Chisholm fired back, telling The New York Times shortly before the election, “The party leaders do not like me. I have always spoken out for what I believe; I cannot be controlled.”

The insults propelled Chisholm to campaign even harder, taking to the streets with a loudspeaker, announcing, “Ladies and gentlemen … this is fighting Shirley Chisholm coming through.” She was a well-known community activist and precinct worker, and she would shake hands with anyone. She also spoke fluent Spanish, connecting with the growing Puerto Rican population. Many new voters were registered during that time, and they turned out to the polls on election day.

When Chisholm defeated Farmer by a two-to-one margin, the question of whether a woman could, or should, go to Congress had been answered. “Nothing can stop you if you have confidence in yourself and the people dig you,” she said following the election.

No intention of being quiet

Photo by Warren K. Leffler, Library of Congress.

At that chaotic moment, 50 years ago, Chisholm made history as the first black woman elected to Congress. She took her seat in the 91st U.S. Congress in January 1969. Busloads of supporters traveled from New York to Washington, D.C., to celebrate with her. Among the other newly elected representatives were two African American men (Louis Stokes of Ohio and William L. Clay Sr. of Missouri), which boosted the number of black representatives from six to a record nine. At the time there were 10 other women in Congress (nine out of 435 seats in the House, and one out of 100 seats in the Senate).

“If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.” —Shirley Chisholm

In some ways, winning the election had been the easy part. Chisholm entered national politics at a time of civil unrest. The white, male status quo was being challenged by massive protests for civil rights and gender equality, and against the war in Vietnam. Violent attempts to suppress progress and silence the outspoken turned deadly; in 1968, the same year Chisholm ran for Congress, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, as was New York State Senator and presidential hopeful Robert F. Kennedy. Chisholm also endured death threats and assassination attempts.

Being outspoken and unpredictable had become something of a trademark for Chisholm, and, while some of her colleagues were welcoming, most gave her a wide berth. (The men of the 91st Congress included Ted Kennedy, Donald Rumsfeld, Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush.) If she felt shunned under the Capitol dome, Chisholm didn’t let on at the time; she felt that responding emotionally wouldn’t serve her or those who voted for her. But many years later she said, “For the first two, three months I was miserable. The gentlemen did not pay me any mind at all. … It was horrible.”

Chisholm used to read a newspaper at lunch because no one would sit at the table with her. But she wasn’t there to make friends. Around that time she told The New York Times, “[I’m] supposed to be seen and not heard. But my voice will be heard. I have no intention of being quiet.”

Chisholm spoke up early and often. Just a few days into her term she made news by standing up in the Democratic caucus and rejecting her committee assignment. While new members of Congress rarely had a say about which committees they landed in, Chisholm thought a “sanctified system” that didn’t allow elected officials to represent the interests of their constituents was ridiculous. She had been assigned to the House Committee on Agriculture, specifically the forestry and rural development subcommittee, but felt she could better serve her diverse, urban district working on issues of labor or education. Chisholm was often stern but relied upon a sharp sense of humor to drive a point home. Referring to a well-known novel by Betty Smith, she told The Washington Post, “Apparently all they know here in Washington about Brooklyn is that a tree grew there.”

Chisholm was accused of grandstanding and was told by then-House Speaker John McCormack to be a “good soldier” and take her appointed committee seat. But she did not and was ultimately reassigned — to the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, which, while not her top choice, was somewhat more applicable to her base. “There are a lot more veterans in my district than trees,” she quipped.

Chisholm didn’t stop there. In her first floor speech in March 1969 she railed against what she called an unjust war in Vietnam, delivering a scathing critique of President Richard Nixon’s budgeting for an elaborate weapons system over the needs of disadvantaged children in his own backyard.

“Unless we start to fight and defeat the enemies in our own country — poverty and racism — and make our talk of equality and opportunity ring true, we are exposed in the eyes of the world as hypocrites when we talk about making people free,” said Chisholm. (Later, she was one of 19 representatives willing to hold hearings on the Vietnam War.) Those who had not come across such a skilled female orator and debater before dismissed her as “pushy,” “brazen” or “overbearing,” according to “A Minority of Members: Women in the U.S. Congress” (1973) by Hope Chamberlin.

Chisholm went on to serve on several powerful panels and influential committees during her seven terms in Congress, ultimately fighting for the same causes she had championed upon arriving in Washington. She worked for social and economic justice programs like Head Start, school lunches and food stamps, and argued for access to a quality education for all. Chisholm also advocated for the rights and empowerment of the poor, minorities and women.

Acknowledging her work as a tireless legislator pays tribute to Chisholm, says Preston Smith, professor of politics and chair of the politics department at Mount Holyoke. “Chisholm’s work in Congress is concrete, palpable. She did the work for her constituents, and, as far as I can tell, they benefited. That’s important,” he says.

Chisholm spoke often about women’s rights as human rights and was a proponent of the Equal Rights Amendment, which would guarantee legal rights to all citizens regardless of sex. In August 1970, Chisholm looked out over a sea of male faces and spoke movingly on the House floor in favor of the resolution. She said the ERA “represents one of the most clear-cut opportunities we are likely to have to declare our faith in the principles that shaped our Constitution. It provides a legal basis for attack on the most subtle, most pervasive and most institutionalized form of prejudice that exists. Discrimination against women, solely on the basis of their sex, is so widespread that it seems to many persons normal, natural and right.” Ultimately ERA ratification failed and, to this day, sex equality is not protected — except where it pertains to the right to vote — by the Constitution.

Unbought and Unbossed

At this time leaders of the loosely organized black political establishment were talking seriously about whether or not to support an African American candidate for president. Black candidates were winning some highly visible races, and black voters comprised 20% of the Democratic Party base. But there was disagreement on how to flex this new electoral muscle. Strategists knew a black candidate for president would be a symbolic move at that moment in history, so would it be safer to support a white candidate with a progressive agenda?

While others were spinning their wheels, Chisholm shifted into gear. Without asking for endorsements or donations — or permission — she announced her candidacy for the 1972 Democratic nomination for president as a “catalyst for change” in reshaping society.

“A house divided cannot stand,” she said during her presidential candidacy announcement, quoting President Abraham Lincoln. She acknowledged that voters were sick of corrupt, self-serving politicians and that it was time to stand up for what one believed in, to follow her lead. “My presence before you now symbolizes a new era in American political history,” she said. “Americans all over are demanding a new sensibility, a new philosophy.”

Chisholm was challenging nearly 200 years of white male leadership in the U.S. government. But she was also confronting what she saw as the male privilege of the civil rights movement and the white privilege of the feminist movement. Prominent feminists, who were mainly white women, were also split on her candidacy, and many felt it would better serve their cause to unite behind a winning candidate whose ear they could bend toward equal rights. Ultimately, Chisholm didn’t get the complete backing of either black men or white women. On the night in Brooklyn when Chisholm announced her candidacy, standing beside her were Ronald Dellums (D-Calif.), an African American representative and later mayor of Oakland with whom Chisholm had founded the Congressional Black Caucus, and feminist activist Betty Friedan (co-founder of the National Women’s Political Caucus with Chisholm, Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem and others). But others were conspicuously absent — like black Manhattan borough president Percy Sutton and Abzug, the white feminist leader and newly elected U.S. representative from New York.

From the onset of her candidacy, gender was a prominent issue. When Chisholm entered the race, eminent CBS anchor Walter Cronkite reported, “A new hat, rather a bonnet, was tossed into the Democratic presidential race today. That of Mrs. Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman to serve in Congress.”

Chisholm didn’t shy away from addressing gender discrimination. In her 1970 autobiography, she wrote: “Of my two ‘handicaps,’ being female put many more obstacles in my path than being black.” Some people tried to humiliate or to discredit her by insulting her looks. Hecklers on the campaign trail shouted that she should stay home to take care of her husband and to clean her house. Following Chisholm’s presidential bid The New York Times reported, “Though her quickness and animation leave an impression of bright femininity, she is not beautiful. …Her face is bony and angular, her nose flat and wide, her neck and limbs scrawny. Her protruding teeth probably account in part for her noticeable lisp.”

But Chisholm wasn’t looking for approval, and she powered on. “Unbought and Unbossed” was her motto, and instead of building bridges to other politicians, she focused on building a coalition of the disenfranchised (women, people of color, working class and young voters). Her platform included a progressive stance on social programs, gun control, civil rights and prison reform, and opposed police brutality. Chisholm raised a modest $95,000 while campaigning nationwide (other candidates at the time spent as much as $1 million on their primary campaigns) and got her name on 12 primary ballots. When she wasn’t invited to debate her male opponents on prime-time television she sued, and won.

The field of nominees was crowded, and Chisholm knew she couldn’t beat the party favorite, but she had a broader vision. Her strategy was to win as many delegates as possible, then offer the front-runner those votes in exchange for his support on core objectives. Her power brokering was ultimately unsuccessful, but Chisholm got 152 delegate votes, or roughly 10% of the total vote. It was more than expected, given her lean campaign financing.

At the Democratic National Convention in Miami in July 1972, in a surprisingly impassioned speech, Percy Sutton from New York nominated Chisholm for the presidency. “This candidate, this lady of determination — in the course of her candidacy, and often in the face of scorn and ridicule from many sides — resolutely continued in her passionate demand for freedom of spirit and human dignity — for all Americans, of all conditions of life,” he said. Sutton continued that Chisholm’s “courage” and “candor” in fighting all forms of human prejudice “made many Americans look deep within their hearts and souls for that which is generous, honest and noble.”

The early 1970s was a period of dramatic social change, says Adam Hilton, assistant professor of politics at the College who specializes in U.S. elections and has done extensive research on the time period in which Chisholm stormed the national stage. It was a critical moment for the Democratic Party in particular, which was shifting from “predominantly white, middle-class and middle-aged to becoming a party that was much more associated with insurgent movements of the time — of students, women and people of color,” Hilton says. “It’s almost impossible to look back from the present and not see connections between contemporary forms of progressive politics and the foundation laid down by Chisholm and other figures of that particular era.

Shirley Chisholm and Mount Holyoke President Elizabeth T. Kennan ’60 at Commencement in 1981. Photo courtesy MHC Archives and Special Collections.

Ask questions, demand answers

While Chisholm never served as president, her legacy and inspiration were far reaching. Elected to serve in the 93rd Congress (1973-1975) were a record-breaking 17 African Americans, including three more women. One of them, Yvonne Burke (D-Calif.), told The Washington Post at the time, “There is no longer any need for anyone to speak for all black women forever. I expect Shirley Chisholm is feeling relieved.” In 1974 Chisholm landed on the Gallup Poll list of “Top 10 Most-Admired Women in America,” on which she placed sixth (tying Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and ahead of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Coretta Scott King).

In 1981, while still in Congress, Chisholm was invited to give the commencement address at Mount Holyoke. She told graduates that even if they were disheartened by the government and doubted their ability to make any meaningful change, they must apply their knowledge, energy and talent in the pursuit.

“Do not assume that you are powerless, that you cannot make an impact,” she said. “Many of the great endeavors throughout history have resulted from the actions of and commitment of one individual.” Chisholm urged the class of ’81 to “ask questions, demand answers, do not just tend your garden, collect your paycheck, bolt the door and deplore what you see on television. Too many Americans are doing that already.”

“Many of the great endeavors throughout history have resulted from the actions of and commitment of one individual.” —Chisholm in her speech to the Mount Holyoke graduating class of 1981

A year later, Chisholm announced her retirement from Congress. She had never planned to spend her whole life in politics, she said, while also admitting she was demoralized by the political scene. But she believed in young people, and so she returned to teaching, taking a position at Mount Holyoke in 1983. For five years she was a professor in the sociology and anthropology departments and taught Congress as a Complex Organization, The Social Roles of Women, Urban Sociology and The Black Woman in America.

Chisholm’s teaching had a profound influence on her students’ later life and work. Kayla Jackson ’86 enrolled in two sociology classes with Chisholm. She was impressed by her professor’s rigor, recalling how Chisholm took a 4 a.m. flight from New York to teach an 8:35 a.m. class.

“She would show up every day in a suit, made up, ready to go, on task,” Jackson says — while the students came to class in more casual attire. “After maybe the second week of us showing up in our sweats, I remember there being a change, a conscious decision to get up to put on real clothes, out of respect. She made a commitment to us, and that made an impact on how we showed up for her. She was so well-respected.” Jackson also recalled that Chisholm never sat down; she moved around the room telling stories and engaging students. “She listened, and that’s a trait we don’t often find in our leaders, unfortunately,” she says.

Jackson, who grew up in Washington, D.C., appreciated at the time that Chisholm was a legend, and she was stunned by her humility. “She was so normal, so down to earth, so human. That made a lasting impression,” she says. Inspired by Chisholm’s focus on women and education, Jackson worked for many years on women’s health issues, particularly reproductive health, and now works at the School Superintendents Association, which advocates for equal access for all students to a high-quality public education. “I’m still living and working in D.C. and come across people often who should be like her. She’s the standard by which I measure them — by that level of decency, of heart. Unfortunately, not many of them measure up.”

Chisholm had urged her students not to wait for a seat at the table — but to bring their own chairs. She hoped her revolutionary acts would be an evolutionary force shifting perceptions about who could lead the country and who would vote for them.

“The next time a woman of whatever color, or a dark-skinned person of whatever sex aspires to be president, the way should be a little smoother because I helped pave it,” she wrote in 1973. Reflecting on her political runs, Preston Smith says, “You need people to put their foot in the water, to try it, so that other people who try it perhaps have an easier time.”

The electability of women

Chisholm and Mount Holyoke students on campus in 1984. Photo courtesy of MHC Archives and Special Collections.

On the day she announced her presidential run, Chisholm said, “I stand here before you today to repudiate the ridiculous notion that the American people will not vote for a qualified candidate simply because he is not white or because she is not a male.”

It took decades, but it happened with the election of President Barack Obama in 2008. “She paved the way. It might be harder to imagine a Barack Obama in 2008 without Chisholm in Congress in ’68 or running for the Democratic nomination in ’72,” says Hilton. It happened again in 2016 when Hillary Clinton became the first woman to win a major party’s nomination for the White House and went on to win the popular vote by upwards of 3 million votes. In 2019 a record number of women stood as serious contenders for a single party’s nomination for the presidency.

In the history of the U.S. a total of 365 women have been elected, or appointed, to Congress (116 of those have been women of color). During the time Chisholm served (from the 91st through the 97th) the total number of women in Congress increased from 11 to 23. That number finally broke 50 in 1993 and has continued to climb steadily.

Having the confidence to raise her hand is perhaps Chisholm’s most enduring gift to women and candidates of color. “In our system there are so many ways in which women are discouraged from seeing themselves as representatives, as office holders. Chisholm definitely is a role model and a legacy for them because she didn’t listen to that,” says Smith.

Whether it was the decision to run for office, or to legislate passionately, Chisholm’s legacy of being an individual, overcoming the odds and inspiring action while transcending gender and skin color, endures. In her first memoir, she wrote, “If my story has any importance, apart from its curiosity value — the fascination of being a “first” at anything is a durable one — it is, I hope, that I have persisted in seeking this path toward a better world.”

Living, Learning and Community

This year more than 500 Mount Holyoke students chose to live in a Living Learning Community (LLC), including one named for Shirley Chisholm. Established in 2017 and currently located on two floors in North Rockefeller Hall, the Shirley Chisholm LLC is for students who are of African descent, identify within the African diaspora and/or wish to foster connections between different cultures within the diaspora.

—Written by Heather Hansen ’94

Heather Baukney Hansen ’94 is an independent journalist splitting her time between the U.S. and the U.K. She draws on her politics degree daily to try to understand what’s happening beyond the headlines.

—Portrait of Chisholm by TL Duryea ’94

This article appeared in the fall 2019 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

November 4, 2019

[…] “The next time a woman of whatever color, or a dark-skinned person of whatever sex aspires to be president, the way should be a little smoother because I helped pave it,” she wrote in 1973. […]

Thanks for highlighting such an inspiring woman – I needed to read this now at this discouraging point in our history. I loved the description by Kayla Jackson’86 of the shift in student choice of dress out of respect. Thank you Shirley, I’m so proud of her connection to Mount Holyoke.

Excellent piece! I love the Portrait on the cover. Well written and relevant. Women of color have come a long way thanks to trail blazers like Mrs. Chisholm. We still have a ways to go but it is good to take a minute and reflect on how far we have come and that the impossible is indeed possible if we fight for it.