Into the Halls of Power

Honoring Professor Victoria Schuck’s legendary Washington, DC, internship program and the Mount Holyoke women it set on the path to success

The ornately decorated Brumidi Corridors on the first floor of the Senate wing in the United States Capitol

Vicky Schuck never failed to make an impression. Former students remember her bursting into classrooms like a brilliant whirlwind, holding court in a library office scattered with books and newspaper clippings, and expertly guiding her green convertible Porsche around Blanchard Circle, a silk scarf flowing behind her like a jaunty contrail. (According to one of her protégées, she was a proud graduate of the Bob Bondurant School of High Performance Driving.) Like many formidable campus personalities, she could be polarizing, but she was widely popular, and she understood that realigning systemic power requires strong networks.

“I owe my whole professional life to my Mount Holyoke education and my Vicky Schuck internship,” says Linda Melconian ’70, a longtime Massachusetts state senator who is now on the faculty of Suffolk University. “That internship opened up the world of public service to me.”

Celebrating Schuck’s legacy—she died in 1999—and affirming the profound effect that the Washington, DC, internship program she created has had on the lives of Mount Holyoke College students was the impetus of the Women Leading in Public Service Summit held at Mount Holyoke in early November. For three days, alumnae with prominent positions in public service returned to campus to meet faculty and students and to discuss how best to expand access for women to public-service fields—and what it means to be a woman

in power in the twenty-first century.

“Vicky Schuck instilled in all of us a desire to do the best job that we possibly could,” says Sally Sears Donner ’63, who retired as a policy adviser at a law firm in 2013 and was one of the principal organizers of the summit. “Many of her former interns were extremely successful.”

Linda Melconian (left) and Sally Sears Donner. Photos by Lynne Graves and Erin Schaff

Among them were many for whom the Schuck internship was a life-changing, and in some cases career-making, experience.

When Linda Melconian enrolled at Mount Holyoke, her dream was to be a math teacher—or an Olympic swimmer. “I liked math,” she says, “and, yes, I had other crazy ideas, too. The internship opened up a world that I just did not know.”

Melconian made history when, in 1999, she became the first woman to serve as the majority leader of the Massachusetts State Senate. But her experience in politics started as an intern in the offices of Edmund Sixtus “Ed” Muskie, the former US senator from Maine, and Edward Boland, a congressman who represented Melconian’s native Springfield, Massachusetts, in the US House of Representatives.

“Vicky Schuck knew enough about the different offices and the different people in Washington to place us where we would be doing substantive work,” Melconian says. Her method of securing these internships was direct—she wrote letters to senators and members of congress asking them to participate in her internship program, including a recommended student’s résumé in each letter.

Melconian’s duties included attending committee hearings, writing articles for the Congressional Record, revising transcripts, and resolving constituent issues. She also answered phones, opened mail, and made some important connections.

“One reason working with Muskie was terrific,” she says, “was because my supervisor was Jane Fenderson Cabot ’65, who had been at Mount Holyoke five years ahead of me. Of course, she took a great interest in me because I was a Mount Holyoke student. So I got to work with her and do a lot of legislative research as well, which was wonderful exposure to the whole legislative process and the issues that were current at the time.”

Melconian’s relationship with Cabot eventually tipped her to the job that launched her career. After graduation, Melconian worked on Muskie’s presidential campaign and, just as that job was ending, learned from Cabot that Judith Kurland ’67 was leaving her position as legislative assistant to Congressman Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill Jr. of Massachusetts.

“So I called Eddie Boland, the congressman who knew my work,” Melconian says. “He called back and said, ‘They’re going to be calling you to interview you. I told them great things.’”

She took the call, and got the job. When O’Neill became House majority leader, Melconian became his chief legislative assistant and, after earning a law degree from George Mason University, assistant counsel. In doing so, she became the first woman to gain access to the floor of the House as a professional staff member in all three leadership offices. She went on to become the first woman from western Massachusetts elected to the State Senate, where she fought successfully for laws that banned discrimination in genetic testing and mandated access to health insurance for women and children.

At Suffolk, she runs a Washington, DC, internship program of her own.

“I don’t think I ever consciously thought ‘I’m going to establish a Vicky Schuck internship program here at Suffolk,’” she says. “But as I got into it I thought, ‘This is just exactly what I experienced.’”

Initiated in 1949, Schuck’s program was the first of its kind, and it inspired similar innovations at countless other colleges and universities. Schuck’s practical knowledge of politics not only opened doors but made old barriers seem obsolete.

Susan Shirk. Photo by Joshua Sugiyama

“Vicky Schuck was engaged in real-world politics. It wasn’t just a subject you studied in her classroom,” says Susan L. Shirk ’67, a former US deputy assistant secretary of state who is now chair of the Twenty-first Century China Program at the University of California, San Diego. “And, especially for a generation of women who in the past had not had opportunities for these kinds of careers, having that kind of real-world experience was very important.”

Shirk started in Professor Schuck’s first-year survey, Parties and Politics 101. Impressed by Schuck’s vibrant blend of charisma and rigorous scholarship, she signed on to do independent work with Shuck the following year, examining how high school history textbooks depicted political parties in American history—a topic close to Schuck’s heart.

“The textbooks took a pretty negative view of party politics,” Shirk says, “and Vicky Schuck’s strong belief was that strong political parties are good for democracy.”

Schuck’s views were formed, in part, by first-hand experience in government. During and after World War II, she worked for two federal agencies: the Office of Price Administration, where she was the principal program analyst from 1942–1944; and that agency’s subsequent incarnation, the Office of Temporary Controls, where she served as a consultant from 1945–1947. She later served on President John F. Kennedy’s Commission on Registration and Voting Participation.

“Vicky Schuck felt that politics was a noble profession,” Shirk says, “and she wanted to teach her students how American politics worked and encourage them to go out there and really contribute and, ideally, to run for elected office.”

Vicky Schuck’s Legacy: In 1974 Mount Holyoke alumnae established The Victoria Schuck Endowment Fund to continue Schuck’s legacy of providing students with internship experiences to ascend through political and public-service sectors. Today, through the Weissman Center for Leadership, students interested in government, public policy, advocacy, or running for office can participate in the Leadership and Public Service Program.

Schuck’s career blended the political with the academic. Born in 1909 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, she attended college at Stanford University and then taught there, earning a doctorate in 1937. She served as an assistant professor at Florida State College for Women from 1937 until 1940, when she became a member of the political science department at Mount Holyoke, where she remained until 1976. She served as President of Mount Vernon College in Washington, DC, from 1977–1980 and, in 1988, the American Political Science Association established an annual award in her name for “the best book published on women and politics.”

Shirk was somewhat unusual among Schuck’s protégées in that she had not jumped in with both feet to the study of American politics; her primary interest lay instead in China and Asia. As if by magic, Schuck found an internship that was a perfect fit.

“I have no idea how she did it,” Shirk says, “but she got me a great internship in Washington, in the State Department at the Office of Vietnamese Refugee Affairs. It was during the Vietnam War, and I was opposed to American policy in Vietnam, but this was the office taking care of the refugees. I felt it was only morally proper and completely defensible that we should be trying to take care of the refugees—and, you see, it was related to Asia.”

After Mount Holyoke, Shirk continued her studies at the University of California, Berkeley, and earned a PhD at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, exploring the consequences of Mao Zedong’s educational policies. She went on to help found the political science department at the University of California, San Diego, and from 1997–2000 she served under President Bill Clinton and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright as deputy assistant secretary of state in the Bureau of East Asia and Pacific Affairs. Her success owed a lot, she says, to Mount Holyoke and her mentor there.

“Vicky Schuck was comfortable with power, and she wanted her students to be comfortable with power,” Shirk says. “The ambition to contribute to public service, and then to be effective in doing it by trying to work with people and have the kind of power you would need to get something done—that was a lesson from Vicky Schuck.”

Judith Kurland (left) and Judith Lonnquist. Photos by Lynn Graves and Katie Brase

Longtime employment and civil-rights lawyer Judith Lonnquist ’62 agrees.

“Vicky Schuck wanted to bring more involvement of confident, capable women into the political scene—into the halls of power, where women had rarely gone,” Lonnquist says.

One way Schuck helped to create confident, capable leaders was by challenging her students at every turn. Her reputation as a demanding teacher was legendary.

When Lonnquist—who has since been named one of Seattle’s 100 most powerful women—walked into Schuck’s classroom as a first-year student, she wasn’t sure what to expect. All she knew was that her sister Jill, who had graduated from Mount Holyoke in 1957, had told her that she had to take a class with Schuck.

“The first day of the class, Vicky is reading through the roster of students and comes upon my name, and she asks me if I were any relation to Jill Lonnquist ’57,” Lonnquist says. “I said, ‘Yes, she’s my sister.’”

Schuck’s next words were enough to make even a seasoned scholar squirm: “Define politics.”

A startled Lonnquist forged ahead.

“And I guess I did all right,” she says, “because after that we became friends!”

Over the next four years, Lonnquist and Schuck often met at “Glessie’s,” or Glesmann’s Pharmacy, the legendary pharmacy and soda fountain whose bibliophile owner Romeo Grenier would soon open the Odyssey Bookshop a few doors down on College Street.

“The thing to do for Holyoke students during my vintage,” Lonnquist says, “was to grab the New York Times and go sit in one of the booths at Glessie’s, and people would rotate through there. You could always find friends and faculty coming in for a coffee or a Coke.”

One aspect of Schuck’s teaching that Lonnquist and other alumnae remember as especially rewarding was her insistence that her students get involved in politics at the grassroots level. As part of class work, Schuck would send students out to do neighborhood surveys in much the same way that campaign workers canvas potential voters.

“That was a phenomenal experience,” Lonnquist says. “We went to these apartments in Holyoke that appeared from the outside to be rather tired and worn down, and yet you would be invited into the apartment and nine times out of ten they would be clean and vibrant, like a little oasis in the middle of the housing projects. I grew up in the suburbs of Chicago, in a well-to-do, middle-class neighborhood, and that was eye-opening for me.”

The internship Schuck procured for Lonnquist—with Paul H. Douglas, who was then the senior senator from Illinois—was also illuminating.

“Douglas was a professor himself, and he never got out of teaching mode,” Lonnquist says. “I got to know who was in City Hall, who you would call if you needed to discuss x, y, or z—the practical politics of government. And yes, to have worked with Paul Douglas did give me a nice big credential on my political résumé.”

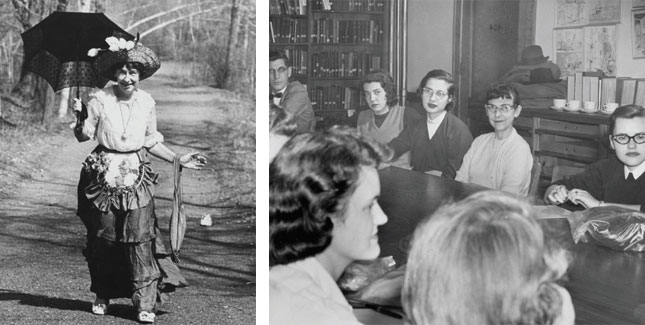

Professor Vicky Schuck taking a stroll on campus in an undated photo; Schuck (second from right, facing camera) with students in a class at the Amherst-Mount Holyoke study center, a precursor to the Five College Consortium, 1956. Photos courtesy of MHC Archives and Special Collections

Douglas suggested to Lonnquist that if she wanted a career in politics, she should go to law school, a piece of advice that would change the course of her life. She earned a law degree at the University of Chicago and, as a result of her internship with Douglas, served as a law clerk to the chairman of the National Labor Relations Board that, in turn, led to a fifty-year career specializing in employment and civil-rights law. It was not simply Schuck’s connections, she says, but also her example that was crucial.

“Vicky was the first role model outside my family who modeled for me what it meant to be a strong, intelligent woman,” Lonnquist says. “There were many people at Mount Holyoke who encouraged us to go out and be uncommon women, and that was a very clear message to which Vicky subscribed. I think that’s why I was so excited about bringing all these interns back to campus for the summit. It is always so pleasurable to see the range of experiences and brilliance and accomplishments that you find, because we all were exposed to really powerful and wise people.”

Melconian likes to tell a story about the day she was sworn in as a state senator. She had arrived in Boston with a triumphant cohort on a chartered bus and, with the ceremony several hours off, somebody suggested the group visit Melconian’s new office in the Massachusetts State House. When the party trooped up the stairs and burst through the doors, there, sitting quietly on the receptionist’s desk, was Vicky Schuck.

“I had no idea she even knew I was running for office,” Melconian says. “I had had no contact with her during the campaign. How she got there, I don’t know. But Vicky Schuck was resourceful. She knew what to do, where to go, and how to make things happen. She was there waiting for me—to welcome me in my new political home.”

—By Abe Loomis

Abe Loomis is a freelance writer based in western Massachusetts.

This article appeared in the spring 2016 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

April 13, 2016

My experience as one of ” that Schuck woman’s interns” –summer of 1960, Washington–was pivotal in my professional life. As others have said — we learned how policy was developed , how politics actually worked and the relationship of the two. ….. It was fun too