Right is of No Sex. Truth is of No Color.

The daughter of abolitionists and a leading suffragette, Helen Pitts, class of 1859, fought for civil rights long before her marriage to Frederick Douglass

Helen Pitts Douglass, class of 1859, and her husband climbed excitedly into a hansom cab outside the Grand Central Hotel in Lower Manhattan, her slight frame contrasting with his powerful build. It was noontime, and the city wore a cap of clouds that kept the day warm. At that hour the street would have been crammed with other horse-drawn buggies, kicking up dust as they went. As the couple made their way down Broadway they likely saw people rushing between shops beneath striped awnings overhanging the sidewalks. En route to the pier where they would meet their steamship the two may have caught a glimpse of the newly completed Brooklyn Bridge. It was September 12, 1886, and Helen and her famous husband, Frederick Douglass, were headed to London.

In the two years since they had married, the couple’s resolve had been tested. Tribulation came not from under the shingled roof of their home, Cedar Hill, in Washington, DC, but from beyond—from their families, friends, colleagues, and, certainly, from many strangers. The problem for most people clucking their tongues disapprovingly was that Douglass, the famous orator and social reformer, was black, and his not-so-famous second wife was white.

A being of infinite scope

However revolutionary the act of marrying across racial lines was at the time, Helen was a product of her upbringing. She grew up in Honeoye, in upstate New York, a hamlet in what is now called Richmond. Her grandfather founded the village (originally called Pittstown) after fighting in the American Revolution.

Helen herself was a ninth- or tenth-generation descendant of six Mayflower passengers who formed a long line of maverick minds. Her kin included powerful political, literary, and religious figures who inspired and influenced thought and action. From one family branch her presidential relations included John Adams and John Quincy Adams and from another Ulysses S. Grant, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Rutherford B. Hayes. Other distant cousins included William Cullen Bryant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Henry David Thoreau.

By 1838, the year Helen was born, the influential religious leadership in Honeoye preached that slavery must be abolished and that congregants must join the fight. In the eyes of their minister true Christians actively resisted slavery, and the Pitts family did so avidly. Reform-minded politics led Helen’s father, Gideon, to invite a prominent anti-slavery speaker to Honeoye in 1846. Helen was eight years old when Frederick Douglass first came to the town, captivating audiences with his booming voice and obvious intellect. On that occasion, and for decades beyond, Douglass was an honored guest in the Pitts family home.

Years later Helen would doubtless have known her home was a stop on the Underground Railroad. The Pitts mansion, located smack in the middle of Main Street, was an important link between the towns of Naples and Avon, a way station that Douglass had helped Gideon Pitts establish. Over a decade, the Pitts family hid in their cellar runaway slaves transported via a false-bottom hearse from a Naples undertaker. By some accounts, more than six hundred former slaves traveled through the Pitts’ basement passageway.

In 1857 socially conscious Helen landed in South Hadley. There were three classes on campus in those days, and eighty-eight students in her cohort. She was among a growing number of young women from all over New England who were leaving home for a seminary education, a move that the feminist-leaning Pitts family greatly encouraged. (Two of Helen’s sisters also pursued higher education: Jennie, class of 1859, at Mount Holyoke, and Eva at Cornell.)

At the time, Mount Holyoke complemented students’ religious upbringing, and all students worked to keep the campus running by cooking and cleaning. It was otherwise a unique place for young women to pursue their studies of languages, literature, philosophy, and science, and participate in discussions with other intelligent women. They were required to do calisthenics daily but took time out for fun—frequent sledding outings and trips throughout the Pioneer Valley. It cost $75 per year to attend Mount Holyoke in the late 1850s, a considerable sum even for the wealthy Pitts family.

Helen would have felt at home among her many social-reform-minded classmates. Long before she arrived on campus the sermons and speeches of the celebrated Henry Ward Beecher (brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin) were a hot topic. Beecher had been educated at Amherst College, and his sister Catharine was, like Mary Lyon, a pioneer in women’s education. Until her death in 1849, Mary Lyon and the Beechers had been close. Slavery and liberty were inherently incompatible, Beecher preached, and “one or the other must die.”

In opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, many Mount Holyoke students sympathized with the anti-slavery cause. When the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed in 1854, it was known on campus as the “Downfall of Liberty, 1854.” The legislation repealed the Missouri Compromise, allowing slavery in the territory north of latitude line 36° 30´N, and led to protests that were a prelude to the Civil War. On Independence Day that year, students wore black armbands and draped everything they could in dark fabric. The abolitionist sentiment prevailed, as described in an essay by Anna Edwards, class of 1859. “The African has . . . suffered cruelly at the hands of our countrymen,” she wrote, and “doing our utmost for their emancipation from the bondage of Satan” was a priority.

A shift was also taking place in thinking about the purpose of educating women. Margaret Fuller’s book Women in the Nineteenth Century was read aloud on campus during Helen’s time. In it, the women’s rights activist and literary critic wrote, “So much is said of women being better educated, that they may become better companions and mothers for men. . . . But a being of infinite scope must not be treated with an exclusive view to any one relation. Give the soul free course, let the organization, both of body and mind, be freely developed, and the being will be fit for any and every relation to which it may be called.” Unlike most of her classmates, who spent just one or two years at Mount Holyoke then moved on swiftly to marriage and motherhood, Helen finished her degree.

Possessed of a fiery temper

Helen entered adult life in the midst of the Civil War. Instead of remaining in the relative safety of Honeoye she took a teaching job in Norfolk, Virginia, in May of 1863. Just a month earlier, the Brute Street Baptist Church had opened a school exclusively for freed slaves, a project of the American Missionary Association (and an extension of the school across the river that became Hampton University). As she had indicated in an earlier class letter, it was the job Helen had been hoping to land.

Roughly twenty more teachers arrived in Norfolk by September of 1863, and by the end of that year there were more than three thousand students of all ages at the school. Teaching in Norfolk was a dangerous social experiment. Just a year prior the city had been surrendered to Union forces, and many Confederate sympathizers in town were up in arms about a school for African Americans and tried to have it shut down. The unrelenting harassment of her students angered Helen. She “immediately caused the arrest of the offenders and they were all fined,” said O.H. Stevens, a longtime Pitts family friend, in an interview years later. Amid angry residents and rampant disease, Helen taught for over a year. Only when falling ill (most likely with tuberculosis) did Helen return to Honeoye, where she was bedridden for years.

In the late 1870s Helen moved to Washington, DC, to live with her uncle Hiram on property adjacent to Cedar Hill, the stately home of Frederick Douglass and his longtime wife, Anna Murray. While there Helen became an officer for the feminist, moral-reform newspaper, The Alpha. As the corresponding secretary she chose letters for publication and moderated heated discussions on everything from women’s right to vote and sexual reproductive health, to whether or not a woman should be blamed for inciting men’s ardor with a low-cut dress. The newspaper was well respected, at least among its readers, who were largely female professionals. Not long before Helen took her post, a letter from Clara Barton (famous Civil War nurse and founder of the American Red Cross) appeared in The Alpha. “May your hands and hearts be strengthened and upheld to the rich harvest of the seed you are so nobly sowing,” she wrote.

As the corresponding secretary for the feminist, moral-reform newspaper, The Alpha, Helen Pitts chose letters for publication and moderated heated discussions on everything from women’s right to vote and sexual reproductive health, to whether or not a woman should be blamed for inciting men’s ardor with a low-cut dress.

Unlike most of her peers, Helen remained unmarried well into her thirties, childless and earning her own living. In 1878 and 1879, Helen taught in Indiana alongside her sister. During that time she and Douglass wrote to one another; their correspondence shows a growing affection and shared interest in literature and politics. While in Indiana, Helen again clashed with locals over racial issues. The local newspaper wrote that she was “sprightly and a good scholar, though unfortunately possessed of a fiery temper which frequently brought her in trouble and caused her to hand in her resignation as teacher of the grade before close of the term.”

Helen then returned to DC to Uncle Hiram’s house and took a job as a clerk in the federal pension office, where she worked for two years. Douglass was the Recorder of Deeds for the District at the time, and when a clerkship opened up in his office in 1882 he hired Helen. Within months Douglass’s wife died, and he sank into depression. He sought solace up North for a time with old friends, including the Pitts family.

Sometime in the next year, 1883, Helen moved into her own apartment in downtown Washington, DC. She and Douglass continued to see one another every day and to exchange ideas. In addition to their politics, “they bonded over gardening, traveling, theater, art,” says curator of the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site Collection, Ka’mal McClarin. Their esteem for one another was evident, and somewhere along the way it grew into more.

A black man’s bride

In January 1884, Helen and Douglass rocked their families, and the nation, when they exchanged “I dos.” The couple foresaw dissent and told no one of their plans. It was tantamount to slipping off to Las Vegas to elope when they were married at the home of mutual friend Reverend Francis Grimké (who, like Douglass, had one black parent and one white one). They left his home, wrote Grimké later, “all radiant and joyful.” Douglass’s children were invited to the wedding dinner that night though none felt fit to celebrate, and Helen’s mother and sister, who were unexpectedly in the nation’s capital that day, only learned of the wedding in the next day’s headlines. “A Black Man’s Bride,” blared the front page of the National Republican (Washington, DC), which also referred to Helen as: “The Woman Young, Attractive, Intelligent, and White.”

Other newspapers were equally damning of the union and, in many cases, wildly inaccurate in their reporting. The claim that the marriage constituted miscegenation and was illegal no doubt rankled the Douglasses, both crusaders for racial equality. Many accounts, including in the New York Times and Washington Post, misreported that Helen was younger than Frederick’s oldest child, putting their age difference at roughly forty years. In truth, Helen was forty-six and Frederick, by best estimates (having no record of his birth into slavery), was sixty-seven years old. The Weekly News, a Pittsburgh-based, African American-run newspaper, was full of contempt over the union: “Fred Douglass has married a red-head white girl. Good-bye black blood in that family. We have no further use for him. His picture hangs in our parlor, we will hang it in the stables.”

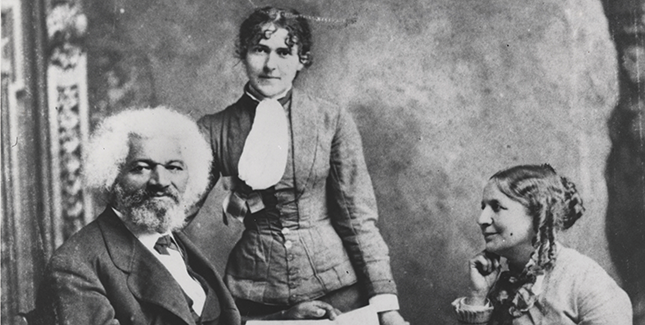

Frederick Douglass with Helen Pitts Douglass (seated, right) and her sister Eva Pitts (standing, center). Photo courtesy of Archives & Special Collections

While the couple responded to very few of the derogatory comments, they did occasionally express themselves in public. Of the union, Helen said simply, “Love came to me and I was not afraid to marry the man I loved because of his color.” Shortly after the wedding, Douglass wrote to old friend and fellow activist Amy Post: “I have had very little sympathy with the curiosity of the world about my domestic relations. What business has the world with the color of my wife? It wants to know how old she is? How her parents and [friends] like her marriage? How I courted her? Whether with love or with money? Whether we are happy or miserable now that we have been married seven months? You would laugh to see the letters I have received and the newspaper talk on these matters. I do not do much to satisfy the public on these points, but there is one upon which I wish you as an old and dear friend to be entirely satisfied and that is: that Helen and I are making life go very happily and that neither of us has yet repented of our marriage.”

A few well-known personalities, some longtime friends, came to their defense. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, with whom Douglass had a tumultuous working relationship, congratulated the couple, wishing “that all the happiness in a true union be yours.” She said, “In defense of the right to . . . marry whom we please—we might quote some of the basic principles of our government [and] suggest that in some things individual rights to tastes should control.” Ida B. Wells, the anti-lynching crusader, was a frequent guest in the Douglasses’ home during their eleven-year marriage. In her autobiography she recalled, “The more I saw of them, the more I admired them both for the patient and uncomplaining way they met the sneers and discourtesies heaped upon them, especially Mrs. Douglass. . . . The friendship and hospitality I enjoyed at the hands of these two great souls is among my treasured memories.”

At home in Honeoye, locals had a better sense of the close acquaintance between Douglass and the Pitts family, and the couple’s shared intellectual interests and social justice sensibilities were understood. O.H. Stevens said at the time of Helen, “She recognized in him a great man and possibl[y] lost sight of his color on just that account. She is a woman of great force of character and would not have taken this step without considering all the results of the alliance. . . . I don’t think the marriage will be unhappy, because both Mr. Douglass and Miss Pitts doubtless knew just what they were doing when they were married. They both are intelligent enough to have foreseen that it would cause widespread comment and they were doubtless prepared to face and disregard all unpleasant notices of the marriage.” The local newspaper, the Livonia Gazette, took it a step further saying, “To deprive them of rights and privileges granted to other intelligent people in the matter of marriage is a proposition repugnant to all justice.”

Their families, however, did not offer the same support. It was understandable that his children were upset, says curator McClarin. They had lost their mother, to whom Douglass was married for almost forty-five years, less than two years earlier. But Helen’s father, despite having been an abolitionist vociferously opposed to slavery, was also outraged. He refused to see the couple and died four years later having never again spoken to his oldest child and having cut her out of his will. Helen’s mother and siblings were also initially obstinately opposed to the marriage, however, several softened with time.

News of the union met with mixed reviews within Helen’s Mount Holyoke network. One classmate, Rachel Cowles Hurd, wrote, “By the way—is it really our Helen Pitts who has married Fred Douglass? How could she? I never discovered it till I saw by the papers that he married a lady from Honeoye, NY, named Pitts. Well our class has distinguished itself!” Apparently Rachel was in the minority in disapproving of the marriage. Helen and Douglass were enthusiastically invited to the class of 1859’s twenty-fifth reunion. In April 1884, Helen replied, “We wish to do so, but Mr. Douglass has so many engagements that I cannot say positively.” Almost as an afterthought, or a defense of their union, Helen added, “[As] well as I know Mr. Douglass I am constantly surprised by some new revelation of the purity and grandeur of his character.”

After they married, Douglass continued a rigorous schedule of writing and public speaking all over the country, on racial tensions and women’s rights. It was, by most accounts, a productive and happy time. During that period, he wrote, “What can the world give me more than I already possess? I am blessed with a loving wife, who in every sense of the word is a helpmate, who enters into all my joys and sorrows.” Helen ran the busy household, handled much of the correspondence, and likely acted as a sounding board for Douglass’s ideas. (Some of his lengthy speeches appear to be written in her hand.)

Cedar Hill, the Douglass family home in Washington, DC, in 1963. Photo courtesy of National Park Service

Ever memorable

But the pair did tire of the near-constant personal scrutiny, and it was from that world of inquiry that Helen and Douglass chose to escape to Europe, at least for a while. As predicted, the trip abroad was a breath of fresh air. “They got some looks and smirks, but for the most part in Europe they didn’t get commented on,” says historian McClarin. In the diary she kept of the nearly yearlong journey, Helen wrote, “People will look at Frederick wherever we go but they wear no unpleasant expressions. . . . Many have a decided appearance of interest.”

After Douglass’s sudden death in 1895, Helen’s focus changed from supporting his ambitions and their shared ideologies to securing his legacy. While Douglass’s will had left almost everything to Helen, including Cedar Hill, his children fought its legitimacy. (It was witnessed by two people, not the three required by law.) Helen secured a loan to buy the house from the children and then took to the lecture circuit, earning money to pay the mortgage. She was again, now in her mid-fifties, working to pay her own bills. Her topics were “Modern Egypt”; “the Hittites”; and the “Convict Lease System.” The cost of booking her for an event was $25. While her lectures were generally well attended, the topic of the convict lease system (basically the newest form of slavery) was of particular interest. One Rochester newspaper reported, “The capacity of the First Universalist Church was tested last night when Mrs. Frederick Douglass told for the second time in this city, her thrilling tale of the horrors of the chain gangs and the crimes of the Convict Lease System of the South. All seats were filled and chairs were placed in the aisles to accommodate the audience that listened with breathless interest.”

Rev. Grimké, the family friend who had married the Douglasses, described Helen’s drive to save Cedar Hill as a monument to Frederick: “It possessed her, she could not throw it off.” In 1900 Helen succeeded in having Congress establish the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association, which would maintain Cedar Hill and its contents after her death in 1903.

Douglass’s children were invited to the wedding dinner, though none felt fit to celebrate, and Helen’s mother and sister, who were unexpectedly in the nation’s capital that day, only learned of the wedding in the next day’s headlines.

Mount Holyoke friend Mary Millard Dickinson, class of 1860, was by Helen’s side near the end. “Helen was true to her convictions to the last. She lived in an ideal world and could not live long enough to realize her hopes,” she wrote. Even thirty years after her death, Grimké defended Helen’s character when he wrote, “Helen Pitts was no common, ordinary white woman. She was educated, a graduate of one of the best colleges in the country, and well read, refined and cultivated, a lady in the best sense of the term.” He recalled, “Among the very last things that she said, as she lay on her dying bed, was: ‘See to it that you do not allow my plan for Cedar Hill to fail.’ That was her dying admonition. I can see the look in her eyes now, and hear afresh the touching tones of her voice as she uttered those words. And it is gratifying to be able to say, ‘It has not failed.’”

“She was ahead of her time,” says McClarin, curator of what is now a national historic site. After Helen’s death, the memorial association joined forces with the National Association of Colored Women, and the house was opened to visitors in 1916. In 1962 Cedar Hill was added to the national park system. The National Park Service (NPS) now safeguards the extraordinary property, preserving roughly 80 percent of the original furnishings. It appears as if the couple merely has stepped out for one of their walks and might return at any moment. The NPS also carries on the educational mission so important to both of its remarkable residents; the site is a tribute to their labors and is as much Helen’s legacy as it is Douglass’s.

According to McClarin, “Mr. Douglass really was fortunate to have two outstanding women in his life. Helen was a true confidante and soulmate and a great supporter of his causes.” Summing up Helen’s later life as well as anyone, Ida B. Wells wrote, “Let us not fail to do honor to the second wife, Helen Pitts Douglass. . . . She loved her husband with as great a love as any woman ever showed. She endured martyrdom because of that love, with a heroism and fortitude.”

—By Heather Baukney Hansen ’94

Heather Baukney Hansen ’94 is an independent journalist who “met” Helen Pitts while doing reporting at the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site for her book Prophets and Moguls, Rangers and Rogues, Bison and Bears: 100 Years of the National Park Service.

This article appeared in the spring 2017 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

April 7, 2017