Welcome Ceremony for New Alumnae

“Scarf Ceremony” Turns a Skeptic into a Cheerleader

By Bonnie Barrett Stretch ’61

“What’s this welcome ceremony for new alumnae?” you may ask. It’s a new tradition, established in 2011 with the class of 1961, designed to welcome new graduates immediately into the worldwide community of MHC alumnae.

The special half-century relationship of the graduating class and the fiftieth reunion class was first officially recognized by the class of 1960, which bonded so well with the class of 2010 that the class of 2011 wanted the same relationship with their grandmother class of 1961.

Historically skeptical of “new traditions,” 1961ers tended to resist the label of “grandmother” but classmates who had arrived by Thursday afternoon dutifully went to Chapin to participate, and were overwhelmed by the event. Class President Bobbi Childs Sampson, in a short elegant talk, welcomed the seniors to “that half century journey that we, the class of 1961, have just traveled,” and recalled our own graduation day seeing the alumnae of the class of 1911, who had graduated into a world in which they could not yet vote! “Truly a different world.”

The ceremony was simple. Members of the grandmother class lined up across the front of the auditorium; members of the granddaughter class formed a line, each facing a “grandmother” who placed around each graduate’s neck a lovely silk scarf in their class color decorated with their class animal.

“I was immediately impressed with the huge number of seniors who were in Chapin for the ‘scarfing,’” recalls Sherry Welles Urner, who is now 1961’s class president. “With each successive wave of seniors, the intimacy seemed to build. Congratulations and questions about future plans seemed to end with hugs and best wishes and genuine emotion, even tears. It was an awesome experience. I was so impressed with the diversity of the graduates, their respect for us, their accomplishments and aspirations. For the rest of the weekend, I noticed yellow scarves as part of graduates’ attire—and if I said, ‘Your scarf is lovely,’ the student would invariably say ‘I love it—and thank you.’ I came to the ceremony as a skeptic, but now I think the scarves were a beautiful bridge to full maturity and alumnae status.”

Journey into Africa

Alumnae confront the challenges with thoughtfulness, humanity, and success

Like so many others in America, Jennifer Kyker ’02 had seen the commercials imploring viewers to send money to help people starving in Africa. They were heartbreaking and compelling, and they’d raised millions of dollars for the cause.

But for Kyker, who first visited Zimbabwe through a high school exchange program when she was fifteen, these organizations’ goals were also painfully narrow. There were plenty of aid groups focused on young children, but by the time those kids had reached adolescence, the programming and funding they needed to thrive had mostly dried up. “Older kids aren’t as appealing—they don’t have those round faces and smiles,” she says. “But that’s when they’re at the highest risk for dropping out of school and contracting HIV. The need is the greatest then.”

It’s part of the reason she started Tariro, an organization that helps provide education and supplies to teen girls who have lost at least one parent to illness or poverty. In the world of international aid, Kyker knows her small organization can help just a tiny segment of the population, but for the sixty or so students that Tariro helps over the course of their adolescence, she knows it will transform their lives. There’s no question that the need is great. Half of the people in sub-Saharan Africa live below the poverty line of $1.25 a day, and literacy rates are lower, collectively, than on any other continent. And more than 22 million people have HIV/AIDS—nearly 70 percent of the worldwide total.

The problems are vast and entrenched. But where some see only hopelessness, many Mount Holyoke alumnae see possibility. It is a philosophy that is practiced in the lives of many alumnae and at the highest levels of the College: President Lynn Pasquerella ’80 makes yearly trips to Kenya’s West Lake District to help a local nonprofit improve the area’s water quality and agricultural practices. (Read the previous Quarterly article about her work.) Mount Holyoke alumnae have devoted weeks, months, and even years of their lives to make a positive difference in the lives of Africans. One person, one school, and one neighborhood at a time, they are changing others’ lives—and their own.

Emmy Murindangamo teaches Heather Baukney Hansen ’94 how to make sadza, a cooked cornmeal dish that’s a staple food in Zimbabwe.

Start With What You Know

The size and scope of the problems in Africa can seem paralyzing, but alumnae have found success by following a simple formula: starting with what they know best.

Perhaps no one knows that better than Zimbabwe native Mufaro Kanyangarara ’07, whose mother died from complications of HIV. When she learned about a $10,000 Davis Foundation grant as a student, she planned a project with Getrude Chimhungwe ’08 to benefit an organization that works with Zimbabwean children orphaned as a result of HIV. Kanyangarara and Chimhungwe won the grant, and with additional funding, they built a chicken farm that the organization maintains to fund specific needs of the orphans, including healthcare. Since its establishment in 2007, the farm has doubled in size (from 500 to about 1,000 chickens) and provides a steady stream of income used to prevent and treat common diseases.

That approach—setting up programs that ultimately can be run without foreign assistance—remains critical to Kanyangarara’s philosophy. She is currently at Johns Hopkins getting a doctorate in international health, but says she plans to return to Zimbabwe, where she can combine her deep knowledge of the culture with the skills she gained through education. “There are a lot of international organizations who come in and try to learn the local setting and implement programs,” she says. “But international organizations should also equip locals with the skills to manage their own programs.”

Fadzi Muzhandu ’05 (right) with Tariro student Tatenda Chizanga, who is now working toward her degree at the University of Zimbabwe.

Kyker’s Tariro has also benefited by working with those who know the culture best. While Kyker can manage fundraising and many administrative details from her home in Rochester, New York, she relies heavily on the organization’s program coordinator and manager, Fadzi Muzhandu ’05. A native of Zimbabwe, Muzhandu works with local schools, parents, and child protection committees as part of her duties. Because of her deep knowledge of the cultural norms and expectations—such as the country’s slower pace or its skepticism about foreign intervention—she can often navigate the cultural terrain more successfully than outsiders.

While the young women who get help from Tariro face an uphill battle, many of the girls have finished their high-school education, and several have gone on to universities. “Tariro is a safe space,” says Muzhandu. “Here, girls have a voice and are allowed to dream.”

Making a Shift

Many of those going to Africa for the first time have strong opinions about specific ways they want to help. But often, as they spend more time there, they adjust their goals.

Such was the case for Liz Berges ’94 and Arden O’Donnell ’97, who spent a year in Zimbabwe in 2002 and 2003. Although they had raised money to build a library before arriving, their time in the country brought more critical problems to light. The well-funded Catholic Relief Services, for example, paid school fees for many children. It was a significant expense and lifted a real burden, but by paying only the school fees and not ancillary expenses, the organization missed a critical piece of the puzzle, says Berges. “In Zimbabwe, public schools require uniforms and school shoes. If you don’t have them, you aren’t allowed in.” Berges wrote about some of these challenges in weekly emails to friends and family at home, and her stories were so compelling that soon people were clamoring to get on the email list. Before long, more than 300 people were receiving her messages, and many of them were sending checks to help out.

Liz Berges ’94 (right) with Lorraine, one of many students helped with school expenses by Coalition for Courage, which Berges cofounded with Arden O’Donnell ’97.

Ultimately, Berges and O’Donnell started their own nonprofit, Coalition for Courage. The funding they receive (more than $100,000 in 2011 alone) pays for everything from food and uniforms to notebooks and pencils.

Their work is making a difference: thanks to their help, fifteen of the students they’ve sponsored have gotten some sort of higher education; thirteen are employed, which is no small feat in a country where unemployment hovers around 95 percent.

While Berges admits that they can’t have the broad reach of larger organizations, the impact they’re making is real. “I think if we weren’t telling these stories, [our donors] wouldn’t be giving to orphans and vulnerable children in southern Africa,” she says. “We can be stewards and make it happen.”

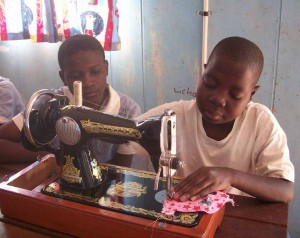

Indeed, their work has inspired several other Mount Holyoke alumnae, including Heather Baukney Hansen ’94 and Bridget McBride ’94, to spend short stints in the country and use their skills to make small but measurable differences. (To read Hansen’s essay, see web extras link at right.) McBride, for example, had received Berges’s emails for years, and decided, almost on a whim, to go with her for a two-week trip to Zimbabwe in 2010. McBride is a nurse practitioner and expected that she would use those skills during her trip. But then she got her packing list, which included pleas from residents to bring sanitary pads. She thought it was a strange request, but then learned that the supplies were expensive for women and teens who had poverty-level budgets.

The help she could provide became immediately apparent: “I wasn’t an expert seamstress, but I knew I could teach them to make their own reusable cloth sanitary napkins,” she says.

Jennifer Kyker ’02 practices a traditional Zimbabwean dance with Tariro students, led by teacher Daniel Inasiyo.

What started as a small project to teach ten girls basic sewing skills and create a practical product quickly expanded to eighty as eager women heard about the idea and wanted to get in on the details. “It took on a life of its own,” she says. “People were talking about it in their church groups, sharing knowledge.”

Gail LaBroad LaRocca ’74 also found success when she shifted her thinking. She had visited Tanzania several times through various organizations starting in 1994, and had happily contributed to efforts related to school expenses and food, among others. But the more often she visited, the more she realized that she wanted to focus her efforts on a single thing: clean water, which spurred her decision to start LifeWaterAfrica.org.

Through connections, LaRocca found a Tanzanian craftsman who created biosand water filters, which can provide clean water for thirty people. Each costs just $150 and, with regular maintenance, will last for years. LaRocca has raised enough money for 100 filters; dozens have already been built and installed. “I might not make a big difference,” she says. “But I can make a small one.” In 2010, LaRocca was named one of 100 “unsung heroines” by the Massachusetts Commission on the Status of Women. Still, she says her work is only beginning. “When I reach 1,000 [filters],” she says, “I’ll be shouting from the rooftops.”

For decades, Mount Holyoke alumnae have used time, money, and influence to improve the lives and circumstances of thousands of people. But McBride says that perhaps the most surprising transformation that occurred was her own. “My experience confirmed what I’ve known intellectually but often chosen to avoid emotionally. People all over the world are suffering and desperate through no fault of their own. My world view has been pried open.”

Rows of makeshift tents at Saloum Port on the Libya-Egypt border house refugees from Somalia hoping to start life anew in another country.

Nayana Bose ’90: Rising to the Challenge

As revolutions roiled the Arab world last year, Nayana Bose ’90 spent three months in Egypt helping those who were fleeing for their lives.

An external relations officer at the United Nation’s Refugee Agency (UNHCR), Bose spends most of her time in New Delhi, India. But when the uprisings in last year’s Arab Spring took hold—swift, powerful, and chaotic—she saw an opportunity to step in and assist at a critical time in history. “It took people by surprise,” she says. “We needed more help.”

Emergency teams from aid organizations were overwhelmed by the need, and when her agency requested volunteers for a mission to Saloum, the official entry point between Libya and Egypt, she applied without hesitation. In March 2011, she traveled to Saloum for a three-month mission.

While thousands of Libyans and Egyptians passed through the port each day with relative ease, others had a more challenging experience. Migrants and refugees from countries including Chad, Niger, Pakistan, Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea, and Ethiopia often got stranded for days or weeks as their documents were processed. As thousands of people fled Libya during the revolution, the numbers of those stranded swelled from hundreds to thousands.

Much of UNHCR’s work was basic and critical, such as assessing asylum claims and distributing plastic sheets so that people could make tents to protect themselves from the ferocious desert storms. The organization also offered blankets, sleeping mats, shoes, and clothes.

“The stories she heard were often heartbreaking—migrants who left their life savings in Libya and teenagers who left their families to avoid military service, only to worry that they would never see their loved ones again.”

As a reporting officer, Bose helped keep her organization—and the world—informed about what was happening. Every day, she spent hours talking with refugees and migrants about why they were fleeing and their concerns about their current situation. She did interviews with international media, wrote stories and Facebook updates for UNHCR, and sent reports back to agency headquarters. “A typical day started at 9 a.m. and ended at 11 p.m., and we worked seven days a week, with five days off after two months,” she says. “It was a punishing pace, but that’s what an emergency mission is about.”

The stories she heard were often heartbreaking—migrants who left their life savings in Libya and teenagers who left their families to avoid military service, only to worry that they would never see their loved ones again. One young man told her he’d lost his best friend in the war, then pressed a poem into her hand that he had written about his experience. “It sounds like a bad Hollywood film,” she says. “But it was their reality.”

But there were also small moments of grace. She grew fond of the people she saw daily, from shopkeepers to bakers. She even came to an uneasy peace with the restrictive Bedouin traditions. And each day, she took forty-five minutes to walk along the corniche, the road by the sea. “Saloum was right on the dazzling blue Mediterranean, and that walk was the highlight of my day,” she says. “It kept me going.”

By June 2011, UNHCR—along with the International Organization for Migration—had helped 36,000 people to cross the border and get home. But for Bose, it is the people, not the numbers, that remain etched in her memory. “I have taken their tales with me back to New Delhi,” she says. “It was a soul-stirring experience.”

—By Erin Peterson

This article appeared in the spring 2012 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

Pioneers of Change

On Being the First Family Member to Attend College

Katie Pierce’s mother couldn’t understand why her daughter wanted to go to college instead of developing a talent she identified in high school for doing her friends’ hair. Alyssa Nelson ’11 and her mother both wept for an hour on freshman drop-off day when it came time to part. Miriam Chirico ’91 never skipped a class during her college career, being acutely aware that each session cost between $40 and $60. Brenda Hernandez ’04 worked thirty-five hours a week in retail at the Holyoke mall during her first two years of college. During her first semester on the Mount Holyoke campus, Zaida Cutler FP’11 had a recurring sensation that at any time someone would tap her on the shoulder and tell her she didn’t belong.

Being part of the first generation in your family to attend college can be as fraught with challenges as it is rich with opportunities, as is borne out by the stories of some alumnae and current Mount Holyoke women. According to Alison Donta-Venman, Mount Holyoke’s director of institutional research, a spring 2009 survey revealed that almost 15 percent of the women at the college come from families where neither parent has a bachelor’s degree. Nationally, about a third of all college students are among the first generation in their families to access higher education, according to numbers compiled by the National Center for Educational Statistics, which is part of the US Department of Education. About a quarter of students seeking a four-year degree fit that category.

Becky Wai-Ling Packard, MHC associate professor of psychology and education, studies the implications of being the first in your family to enter the world of higher education. She also has stories to tell from personal experience. Researchers often see a degree of ambivalence among first-generation college students, according to Packard. “You are trying to strive and everybody understands that’s a good thing,” said Packard, but there are many ways first-generation students hold themselves back, sometimes to the point of unknowingly sabotaging their progress. It’s not uncommon to feel either inadequate or like a social climber who is rejecting her past. Questions like these—Is where I am coming from not good enough? Do I think I’m better than other people because I’m getting this education? Will I even understand where I come from after college? and Why am I sitting here pontificating about sociology while my mother is mopping floors?—can subtly eat at working-class students in elite institutions.

Packard also notices that first-generation students often exhibit an urgency to become overly involved in community service as a way of “giving back,” because sitting in the library and reading seems like a luxury that they and the world can’t afford.

Alyssa Nelson ’11 is fulfilling the educational dreams of her mother (a high school graduate) and grandmother (whose formal education ended after second grade).

Alyssa Nelson, a junior majoring in sociology, grew up in New York City. Her grandmother, who came from Puerto Rico, has a second-grade education and can’t read or write. Her mother graduated from high school and yearned to go to college, but simply couldn’t afford to. So she is determined that her children fulfill that dream. Yet, when Nelson was accepted at Mount Holyoke, her mother “started crying months in advance, asking, ‘Are you sure you want to go so far away?’” recalls Nelson. She now aims to be accepted by Harvard Law School in her quest to become a criminal-defense attorney. At the same time, she is getting her teacher’s licensure. “It’s always good to have a backup plan, in case I don’t do well in the field of law, or I don’t like it, or something happens where it doesn’t work,” said Nelson. In addition to her studies she volunteers at a criminal-detention center in Westfield and works long hours at multiple jobs to make money on her vacations and through work study on campus.

Miriam Chirico ’91 is a professor of English at Eastern Connecticut State University. Her parents came to the United States from Italy and France respectively. “They really wanted me to go to community college if I was going to go to college,” she said. A telling moment was when, on a visit to the MHC campus, her mother, commenting on some women playing lacrosse, said, “You’re really at the wrong school.” Chirico said the remark stemmed from the fact that “the game has such a prep-school look to it, with the plaid skirts and the ponytails.” Her mother’s message was that such pursuits were “beyond my economic level,” Chirico said.

Her response to the opportunities presented at Mount Holyoke was to single-mindedly devote herself to academics, in part because her parents took out a second mortgage on their house to make it happen. She takes pride in having graduated fifth in her class, but in retrospect wishes she’d had a more relaxed attitude toward school. “I could have left campus more often to go on road trips, because that was all part of the college experience,” she said.

Zaida Cutler ’11, a Frances Perkins student who wants to major in English, remembers impressions of Mount Holyoke College from her youth. “I lived in Holyoke all my life. I would drive by the place on Route 116 and look at those gates and say, ‘Oh my God, that is a whole other world. I’m not invited.’” After she was accepted, her first response was to recoil at the risk that going to school represented for her, and she contemplated dropping out almost as soon as she started. A voice inside her head kept asking, “What have I done to myself? Why am I here? Am I wasting time and money?”

Cutler’s deepest fear—“When are they going to figure out that I’m really not supposed to be here?” with her through the entire first semester.

Cutler’s father, who died when she was a baby, was from Puerto Rico, and her mother was the daughter of Italian immigrants. They both worked in paper mills, and Cutler remembers her mother’s distinct unease about Cutler’s early foray into higher education. Mostly an A student in high school, she was accepted at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. She dropped out after two months, in part because of her mother’s misgivings. “What’s it going to do for you? was her way of thinking,” Cutler recalls. Her mother would tell her, “You’re already smart and you can do anything those college girls can do. After four years of college you will still have to get a job, and who is going to pay for that?”

Cutler went to work as a receptionist in a paper mill and was promoted to the accounts department, where it became clear to her that the industry was in decline. After a string of poorly paid jobs, she went to Holyoke Community College, where she got a degree in management in 1997, enabling her to get her current job as a medical records coordinator in a nursing home.

Now, as a Mount Holyoke student, she is realizing that she loves literature and poetry. Even though Cutler hopes to major in English, she is setting her sights on becoming an accountant. “That’s a tradeoff I’m happy to make because I think I will enjoy accountancy just as much as anything else I could do to pay the mortgage,” she said.

She is struck that, because of her economic circumstances, she doesn’t feel as free to follow her bliss. “I’ve met young ladies who are religion majors, and I think to myself, isn’t that nice to be able to do that, but good luck buying a house with that,” said Cutler. “I would love to go for my MFA, but then what, and how do I pay off the student loan? So I have to be practical.”

Now an admissions counselor at Pace Law School, Brenda Hernandez ’04 (right) talks to prospective students about her experiences as a first-generation college student, encouraging them to struggle through the many obstacles to success

Brenda Hernandez ’04 found being a first-generation college student a liberating experience. The oldest of five children growing up in Northampton, she was fourteen when her father died, putting her into the role of second parent to her siblings. She worked at McDonald’s and then at a pharmacy all through high school. She also knew that she loved to learn. Hernandez applied to Mount Holyoke early decision and nowhere else. Once in college, she felt good that she got less pressure from home than some of her classmates. “A lot of students whose parents had been through it really pushed them to say, ‘okay, this is the plan for you.’ I had no one saying that. So I could really go in there and just explore,” said Hernandez. “My mom was definitely 100 percent there for me. I could have gotten Ds and just the fact that I was in college made her so happy. For me to be doing well was a bonus.”

Hernandez recently graduated from Pace Law School and now works as an admissions counselor there. She often talks to prospective students about experiences as a first-generation college student, encouraging them to struggle through the many obstacles to success.

The experiences of Katie Pierce ’03 were more typical of what the academic literature describes as issues that first-generation college students face. Her mother was “confused” by her decision to pursue higher education. “That divide pulled us apart during my initial college years,” she said.

Katie Pierce ’03 found her mom was “confused” by her daughter’s decision to attend college, since Pierce’s early talent promised a successful career in hairdressing.

“My mom wanted me to become a hairdresser; she didn’t understand why I wanted to go to college.” Pierce majored in economics and, until the recession, worked in the investment-management industry for a Boston financial firm.

In retrospect, Pierce wishes she had been less focused on a major she thought would guarantee her a job right out of school. “I’m realizing that I spent much of my college years suppressing my creative side. That keeps bubbling up, and every now and then I feel like I should have done something more creative,” she said. Art and anthropology fascinated her during college. “It was difficult to ignore the spark I felt in those types of classes, but my economic situation kept telling me to focus on things more practical.”

Pierce, who serves as copresident of the Mount Holyoke Club of Boston, said she remembers feeling embarrassed by her working-class roots during college. “It’s definitely taken some growing up and me getting older to realize that it’s nothing that I should be ashamed of,” she said, “It’s what molded me and made me who I am today.”

Professor Packard, whose research on mentoring and persistence is supported by the National Science Foundation, said administrators across the country are focusing on applicants who are the first in their families to attend college “as part of a broader interest in attracting and retaining a diverse pool of students.” The overwhelming majority of people from lower-income backgrounds seeking higher education “use a community-college pathway,” she said.

Mount Holyoke, Packard observes, has a history of attracting students from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds. “I think it’s partly the Mary Lyon legacy of purposeful engagement and community service,” she said. “That is very attractive to people from first-generation college backgrounds because, if their entire family is making a sacrifice for them to go, then they want to do something very meaningful with that education.”

—By Eric Goldscheider

This article appeared in the spring 2010 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

Maggie McGovern ’97: Putting Peace into Practice

“Let there be peace on earth, and let it begin with me,” begins the well-known folk song. Maggie McGovern has taken those words to heart, teaching nonviolent communication to prisoners in San Quentin and trying to improve support services for parolees. She’s working toward certification from the International Center for Nonviolent Communication.

“Let there be peace on earth, and let it begin with me,” begins the well-known folk song. Maggie McGovern has taken those words to heart, teaching nonviolent communication to prisoners in San Quentin and trying to improve support services for parolees. She’s working toward certification from the International Center for Nonviolent Communication.

Every week for a year and one half, she taught groups of eight to twenty-five male inmates—short-termers and lifers—how to consider what motivates their actions, and others’ actions. “Instead of thinking, ‘That guy looked at me; he’s a threat; I’m going to protect myself by punching him,'” Maggie explains, “I helped them slow down, think it through, and realize that 95 percent of the time the person’s not a danger.”

When a prisoner who became a friend was released from San Quentin this year, Maggie realized how little support there is for many experiencing the tumultuous transition from prison to the outside world. “If a man has been in prison for seventeen years but is released, he’s coming into a completely different world with a different set of rules. He’ll experience culture shock just like someone moving to another country,” she says. In addition to practical concerns such as finding housing and a job, parolees often must cope with wrenching psychological issues. “For seventeen years, gaining his freedom has been his purpose. When he’s free, he may feel ‘Who am I? What’s my purpose?’” she explains. “Parolees need way more support,” Maggie concludes, and she plans to create a support program if necessary to make sure they get it.

While working toward that goal, she is also mediating discussions between juvenile offenders and their victims, trying to support both groups; and paying the bills with her empathic coaching business. And when the muse strikes, Maggie is telling prisoners’ stories through original songs. —E.H.W.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/189293832″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Listening to Clothes

Archive Captures Women’s History Through Dress

Above Chapin Auditorium, high up in Mary E. Woolley Hall, we climb the stairs to reach the Mount Holyoke Clothing Archive. I feel a ghost hunter’s anticipation as my guide unlocks the first door and I step into a storage room under the eaves. My overwhelming impression, in this crowded space, is of the ebullience of women’s garments ranging back over more than 170 years, a colorful history in cloth.Theatre Costume Shop Assistant Anna Rose Keefe ’13, my guide, tells me that few items have a known provenance. Most must speak for themselves. The clothes, donated by alumnae and others, are sorted by decade. As I follow the narrative of fashion through the small rooms, I see that, among other things, it’s a branch of art history. A cream wool cape with glass beading (left) and corded trim belongs to 1890s Art Nouveau.

All the clothes, though, are too fragile to be worn on stage. Theatre Arts Costume Shop Manager Elaine Bergeron has explained that the department, custodian of the archive, uses the collection for study and to copy for costumes. In addition to work on shows, Keefe’s tasks include assisting with sorting, cleaning, mending, and, where resources allow, conserving pieces, and entering their details in a new cataloguing system. The department has had some items digitally photographed, Bergeron says, and is working toward making, with the future help of Library, Information, and Technology Services, a searchable online resource for research in textile design, construction, and fashion history.

After the doors are closed and the locks double-checked, I am reluctant to leave. My mind is full of what I’ve seen and the whispers of garments I didn’t get to look at. How can I leave them up here? They have so much more to say.

—By Lynne Barrett ’72

This article appeared in the spring 2012 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

The psychology of clothing intrigues me, the ways it expresses identity and evokes emotion. A strapless evening gown with tulle insets might demand a 1950s figure and posture, while a yellow silk velvet 1920s evening coat offers a welcoming embrace, inviting the wearer to clutch its chinchilla collar and let the hem swing.

Along one rack, print dresses from the 1940s play a bright jazz riff. Full of energy and optimism, these frocks of silk, rayon, or cotton seem made to move. Rayon, I remember, became the can-do substitute when World War II made silk rare. Keefe and I discuss how fashion, once derided as frippery, has become an area of research in economics, history, art, and anthropology.

Women marching in such long skirts won suffrage, but a shimmying beaded shift and a brilliant hand-crocheted jacket from the 1920s flaunt the changes in women’s roles that followed. These bright things seem to scoff at their predecessors’ restraint. I notice, though, that detailed handiwork unites the styles. One woman with a taste for embellishment could have worn both as she strode ahead through time. Looking closely, I feel too the presence of those who did the fine construction of the clothes and their adornment, exchanging woman-hours and eyesight for a living.

I admire the grace of pale, high-collared dresses, the white worn by Jessie F. Maclay Jones (MHC 1910), the ivory from 1916.

A bird constructed of real feathers on a 1950s hat (above) is both saucy and strange, a surrealist fantasy.

A grande dame of a silk taffeta dressdemands attention. As it happens, it speaks French: a label inside the waist belt reads “A. Felix Breveté / Faubourg St. Honoré /Paris.” Breveté means patented, but this design’s silhouette became the rage in the 1890s. Puffed shoulders and ballooning upper sleeves made waists look smaller by contrast, an illusion that returned in the 1980s, as relics in my own closet attest.