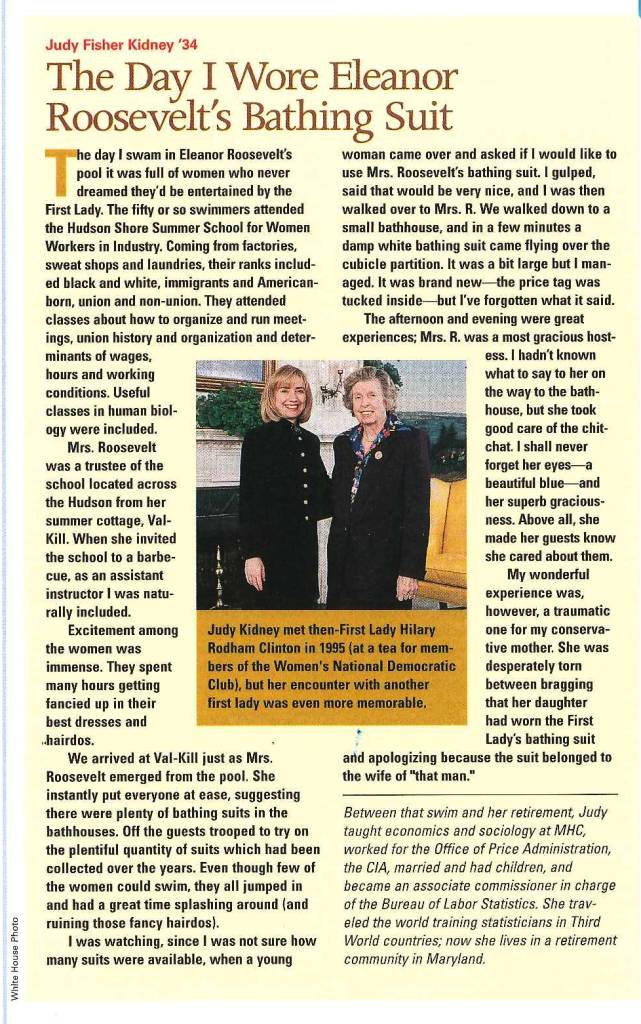

The Day I Wore Eleanor Roosevelt’s Bathing Suit

—By Judy Fisher Kidney ’34

This article appeared in the winter 2001 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

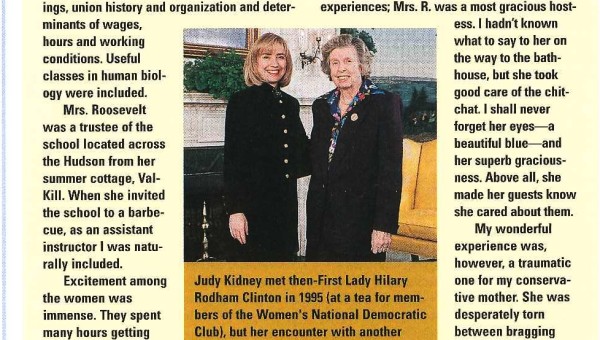

Inviting Children to Observe the World

In her latest book, Kathleen Weidner Zoehfeld ’76 takes kids into the garden.

Growing up on a farm in the Catskill Mountains of New York State, Kathleen Weidner Zoehfeld ’76 spent lots of time outdoors, tramping through the woods with her grandfather, looking for bear signs and porcupine dens, and helping her mom in her big vegetable garden.

Growing up on a farm in the Catskill Mountains of New York State, Kathleen Weidner Zoehfeld ’76 spent lots of time outdoors, tramping through the woods with her grandfather, looking for bear signs and porcupine dens, and helping her mom in her big vegetable garden.

That early experience with the natural world and a longstanding interest in helping technology centered kids get over their nature phobia are what inspired Zoehfeld to write Secrets of the Garden: Food Chains and the Food Web in Our Backyard (Knopf Books for Young Readers).

The children’s book is a journey through the vegetable garden of one family, from spring planting to fall harvest. Narrator Alice discovers all the wonders of a garden’s life cycle, and talking chickens proffer scientific information about everything from composting to nutrition.

“Kids in elementary school have to learn about food chains, and so you can approach it in an abstract way, or you can get kids out into the backyard and let them have fun and get their hands dirty,” Zoehfeld says. She hopes her books will inspire the latter.

A former children’s book editor, Zoehfeld talks to teachers to figure out what they need to help move their curriculum along. The author of more than sixty books for kids in every age group from preschool through middle school, Zoehfeld is skilled at getting the required facts incorporated into a story that is memorable and makes kids want to turn the page.

It isn’t easy. It took her almost ten years to get her first book, What Lives in a Shell?, accepted for publication. It was the mentoring of a Smith alumna at publisher Lippincott & Crowell that first got her interested in science literacy. An English major and art-history minor at MHC, she was fascinated by meshing the written word with visual elements.

Her biggest markets are libraries and schools, and in recent years both have suffered hefty cutbacks in budgets. Nevertheless, her books garner lots of praise and prizes, and Secrets is no different; it was recently recommended by Kirkus, the School Library Journal, and Scholastic News’ “Teachers’ Picks.”

A resident of gardening heaven Berkeley, California, Zoehfeld has a sequel coming out sometime next year called Secrets of the Seasons, and she is also at work on something completely different: a young-adult historical novel.

“It’s good to keep challenging yourself,” she notes. At the start of her career, Zoehfeld wondered if she really had anything to say. She’s answered that sixty times over. But for a writer, that feeling never goes away.

“Can I really do this?” she asks of writing a novel. Alice would likely give her a thumbs-up for braving the unknown in her own backyard.—Mieke H. Bomann

Check out all of Zoehfeld’s books.

Check out all of Zoehfeld’s books.

Inside the Real West Wing: Interview with Mona K. Sutphen ’89

Jillian Dunham: Could you give us a sense of your typical day at the White House?

Jillian Dunham: Could you give us a sense of your typical day at the White House?

Mona Sutphen: It starts around 7:15 with a series of senior staff strategy meetings, and usually a meeting with the president. Those go until around 10:00 … and then it’s back-to-back meetings, maybe with a forty-five-minute break during the day. Usually I’m home about 9:00. We work Saturdays, usually from about 10:00 to about 3:00.

There are two deputy chiefs of staff; I work on the policy- related issues. The job is essentially to ensure, at least for the top priorities of the president and for Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel, that the work of the White House staff is consistent with their expectations.

JD: I’ve read a lot about the president’s morning meetings. What are they like, and do you interact much with the president and advisers in those meetings?

MS:Yes. There’s a senior advisers meeting, which includes about nine of us. It’s usually in the morning, almost every day of the week. It’s usually reserved for the most pressing issues. We cover a lot of strategy. Rahm often sets the tone. Sometimes we go around and talk about issues we need guidance on for the day; sometimes we do it by theme. We might talk about just one issue and drill down pretty deeply into it.

There may have been developments overnight that change how we approach something. Some of it’s tactics; sometimes it’s strategy. Sometimes the meeting is short, sometimes it’s long; it just depends on what’s going on. Sometimes [Emanuel] comes with a laundry list of things he wants to talk about, all the way from administrative matters to major strategy on initiatives such as healthcare or the energy bill.

JD: That sounds like a lot to manage. Could you talk about your two young kids, and how you balance work and have enough time for your family?

MS: Well, it’s a challenge, needless to say. It’s a very intense job. We need to delve very deeply into very complicated issues, quickly, and move from issue to issue, also very quickly. It requires that you get to the central element of the issues and the decisions required, and understand the risks, benefits, and controversies associated with the policy issue you’re working on.

So it’s intense both intellectually and time-wise, but the

nice thing is that it’s not a first-responder kind of job. So if I’m working on something related to EPA regulation, I’m not going to get a call at two o’clock in the morning over that. When I’m home, I can be home.

I do a lot of advance planning—I get no time to myself at all—my weekends are hyper-scheduled so I can get everything organized for the upcoming week with the kids, and spend time with them. When I’m not at work, I try to really be home. There are e-mails and all that, but on the weekends I try to do that when the kids are asleep.

I figure I have to put my Blackberry down at a certain point. When I get home early enough to put my daughter to bed— which is rare—I very much prefer to do that. I would rather face however many e-mails I’m going to have in the morning rather than not have any downtime in the evening. It’s just a tradeoff. Sundays, I try to just be mom.

JD: It’s got to be such a rewarding job. Was there a moment recently at work when you felt, this is why I’m balancing all of this?

MS: Last night. Yesterday we went to a rally for Gov. Jon Corzine in New Jersey and then to the 100th anniversary of the NAACP. The New Jersey event had a campaign rally feel—18,000 people in a stadium with music going—and Obama gave a fantastic speech about healthcare reform, why we need to act now, and why it’s so important. And then we ended up in New York talking about the legacy of race in the US. And Obama was standing there, obviously an example of how far the country has come since the founding of the NAACP. Just last week, we were in Ghana, and Cape Coast, where slaves were held until they got sold and put onto ships … and to go all the way from there to standing at the NAACP last night, it gives you a sense of history. I have those moments every day. There are 1,001 frustrations along the way too, but there are many, many times when I can’t believe I’m working for this man in this point in our history.

JD: What’s it like to travel on Air Force One?

MS: It’s great. If you imagine air travel with a comfortable living room, that’s basically it. You can walk around, you have choices of food … all the things you think air travel should be about. And obviously you get to come and go when you’re ready. You’re never waiting because there’s a flight delay; there are no security lines, no runway delays, and the plane’s always there waiting for you. Are there policy issues you’re working on that make you think, “This is something I’d like to see be an ordinary part of my children’s lives as they grow up”? Sure. So much of the president’s agenda is generationally relevant to me and especially to my kids. We’re trying to plant the seeds for a United States that will be better than the one we grew up in, whether that means figuring out healthcare reform, or education, so that you don’t have a 50 percent dropout rate, or the energy economy—so that we’re not beholden to Middle Eastern oil, but also are being responsible stewards of the planet. A lot of things that were ignored over the last eight years, we are taking a look at and trying to get to the essential issues that need to get fixed.

It’s one of the great things about working for President Obama, and one of the interesting things about working in a time of crisis, that there is more of an appetite to try and get to the root of the problem, and to step back and say, “If you could do it the perfect way, separated from all the water under the bridge, what is the right policy?” We always start at that point—what is the correct answer, how close can we get to that answer based on the constraints we have, and how can we push the envelope as much as possible? We’re doing that with education, with energy … We think we are on the right course, and he’s got a very strong vision.

JD:You worked for the Clinton administration, for then-National Security Adviser Sandy Berger, and you chose to endorse President Obama early. I imagine that with Hillary Clinton in the race, that may have been difficult. What made you endorse Obama?

MS: My husband endorsed Hillary, so we had a split household. He had previously worked with the Clinton Foundation in New York, and we were both very close to then-Senator Clinton. And I think she’s a fantastic person, so yes, it was a hard choice because of the feeling of loyalty, but not a hard choice in terms of who I thought would be a better president. We had met Obama when he first got elected, before he went out on the campaign trail in ’06 and got everybody excited, and I remember thinking to myself, he’s very, very compelling.

JD: Your mother is Jewish and your father is African American, and I read that they had to cross state lines to marry. What are some of the big lessons your parents gave you, and how did their example play a role in leading you to where you are today?

MS: They were both very involved in community organizing and public service. That was an element that ran through our family in a way I don’t think I appreciated growing up, but it’s clearly had a very profound impact on my career choices and orientation. They told my brother and me that we’d be treated differently because we are biracial, but that how others see you doesn’t necessarily have any bearing on how you are as a person. That held us in good stead along the way. Everybody goes through racial identity questions when you’re biracial, much like the president did and I did as well, but if you have a certain level of I don’t find that there are that many compelling people that go into public service in this country, so I figure the least I could do was to spend some of my free time helping him. When I started, I frankly doubted whether he could win. I hoped I could help build the strongest policy platform that he could have. I did not go into it calculating, “he’s going to win and then I can get a good job with the government.” I have young kids and was happy not to be in government. But I care about the country and thought, here is someone compelling. Period.

JD: Do you work with Secretary of State Clinton now?

MS: Sure. She’s incredibly smart and thoughtful and really, really good. I think she will continue to be a great secretary of state. I think in many ways it’s a perfect job.

JD: Do you have a memory of working with the president since coming to the White House? For instance, do you have a standing thing, like you always get coffee together?

MS: No, no, it’s more formal than that. He’s not exactly my generation—but close—and he’s not a very formal person, so while we have conversations like you’d have with any colleague, there’s still a formality there. I definitely call him Mr. President. personal confidence, you can weather that storm better. It’s very strange that I ended up being so interested in international issues because I grew up in Milwaukee, your classic Midwestern town. We went on a couple of foreign trips, but we weren’t any kind of world travelers. But somehow I became interested in seeing the world, having adventures, living in war zones, and all that. There is definitely an adventurous streak in the family.

JD: I guess you could see what you’re doing right now as a kind of global community service.

MS: Yes. I have always felt public service was a sweet spot for me personally because it’s challenging and interesting enough, and you’re having impact at a broader level. It’s not as satisfying as when you’re working person to person, working in a community group, or working with prisoners of war, where you have the human connection—that’s by far the most satisfying work. But it’s also micro. So you are balancing the micro/macro level of impact and intensity of intellectual interest, as opposed to emotional interest, of the work. And I feel Washington strikes a good balance, certainly at this time, when we have such big issues to deal with.

My Voice: 50 Years After The Feminine Mystique, Have Women’s Choices Changed?

The life choices available to Meredith Casey (left) are quite different from those open to her mom (Cindy Carpenter ’83, center) and grandmother (Mary Lou Judd Carpenter ’55)…or are they?

I first read Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in college. It was the early ’80s, and when I came home for winter break, I mentioned to my mother that I had found the book interesting. Her response: “That book changed my life.” I found out later that it had probably changed my life as well.

I was two when Friedan’s book was published in 1963. My mom—Mary Lou Judd Carpenter ’55—was at home with her small children while my father, an attorney, worked. I grew up in the world Friedan described: well-educated, competent women who married well-educated, professional men and found themselves at home with their children. I didn’t experience my mother as unfulfilled, but I do know the message my sister and I received was very clear: You are to have a career. You are to go the places I did not. You are to look at traditionally male endeavors as opportunities open to you.

My mom contends that she just wanted us to be aware that we had choices, but neither my sister nor I heard it that way. We heard that getting married and having children were part of life, but careers were most important. We were not to be dependent on a man, live for our children, or be the default keepers of home and hearth. We were to have careers, financial wherewithal, and independence. This didn’t seem inconsistent to us—we were growing up right along with the women’s movement—and both parents expected us to develop our intellectual and vocational potential. My father spoke admiringly of new women associates; my mother shared examples of young women pursuing graduate work or making it as young executives. My peers and I assumed we would have some sort of career, and many of my classmates had very clear professional aspirations. I marched out into the world with paisley bow-tie and sensible pumps, naively assuming that I would add the family piece along the way.

My reality included all the well-documented challenges faced by working women raising children and managing families. My friends and I lamented how we enjoyed feeling capable at work, but hated feeling short-changed at home. Many of us had been raised by stay-at-home moms, and we aspired to create family lives based on a labor model we didn’t have. Our employers, colleagues, partners, and we ourselves ad-libbed a variety of solutions. Part-time, flex-time, freelance, contract, job-share, even the “mommy track”—all offered only partial solutions and all came with trade-offs.

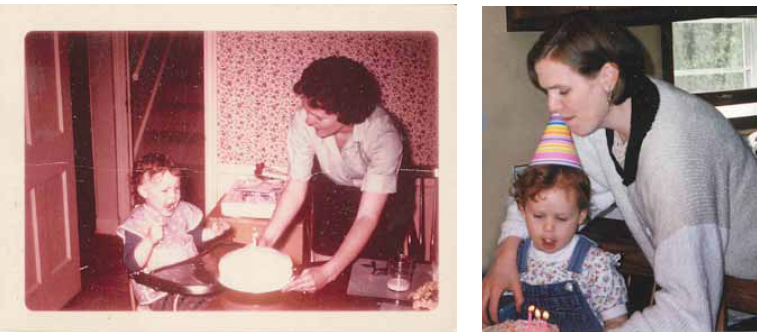

Left: Mary Lou Judd Carpenter ’55 serves birthday

cake to two-year-old Cindy in 1963.

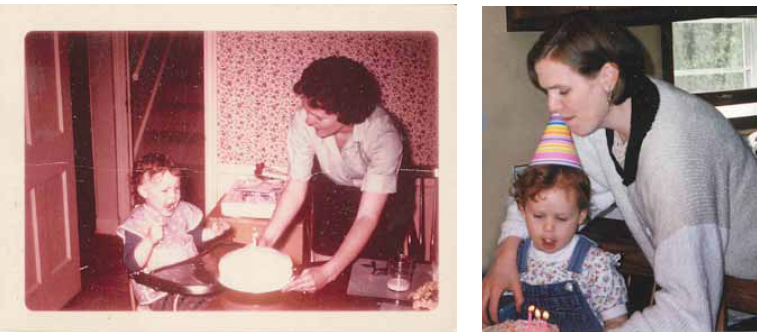

Right: History repeats itself as Cindy Carpenter ’83, now the mom, celebrates daughter Meredith’s birthday.

This “You have choices” deal didn’t feel like a deal at all. As I juggled work and family, my mother’s life sure looked OK to me: she ran a household, volunteered for causes she believed in, and spent a lot of time with interesting, competent women. She made significant contributions without ever stressing about a paycheck, a promotion, or a performance review. Mom’s carpools ran with precision; her dinners were nutritious and on time; sick children were simply brought along to committee meetings. I know being home with children is uniquely challenging, so I am not minimizing the stress, but I’d wonder whether my mother’s route might have actually gotten me closer to what I wanted: time with family, work I believed in, and the ability to make a meaningful contribution to the world.

This has really come home to me as I raise my daughter, Meredith. She has watched me do the working mother twostep, and once told a teacher that she wanted to be a “client” when she grew up—after all, that’s what Mommy talked about, so it must be important. At age seventeen, she has seen great variety in how families manage work and childcare, and she doesn’t have strong opinions about one way being preferable to another. But what my mother thought were opportunities for me look like purgatory to my daughter. She doesn’t see my career in corporate communications as something to aspire to, although she accepts that it’s important to me and necessary for our family. But what she values from her childhood are the rituals, events, and gatherings that were the first items cut from my to-do list when I ran out of time or energy. I know she would have liked to have a family life more like what I had growing up. Yet, as she prepares for her own future, she is eager to pursue her own passions, and doesn’t view the “home front” as gender-specific territory. She may be no better equipped than I was to understand what the trade-offs really feel like. What am I to tell her about “choices”?

Friedan’s book remains very important, and I don’t want to diminish the problems it portrayed and the challenges that still exist today. I am grateful for the choices available to me and the support I had from my mother and others. I know my daughter has many more options and opportunities because of the women who came before her. But the message I want to impart to her about the choices we have is more qualified and nuanced. I don’t feel the confident conviction that I heard from my own mother: pursue a career you love and the family life you want. My daughter’s world is very different than mine or my mother’s, but I wonder whether the ambivalence I sometimes feel will diminish with successive generations. We’ll have to wait another fifty years to know.

—By Cindy Carpenter ’83

This article appeared in the fall 2012 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

Calif. Town Boasts a High Density of MHC Alums

Emmalie Moseley ’10 holding her laptop with image of Carly Peltier ’13, joining in via Skype from Argentina.

MHC alumnae residing in Brisbane, a small town next door to San Francisco, may have set a record of sorts when they decided to get together recently. Anja Salmela Miller ’56, Elna Miller ’87, Suzanne Howard ’89, and Emmalie Moseley ’10 gathered at Brisbane’s MadHouse Coffee, and were joined remotely by Carly Peltier ’13 via Skype from Argentina.

In addition to sharing their joy of living here and finally meeting, the discussion turned to demographics: The little city of Brisbane has a population of only 4,000, which would make the “density calculation” of MHC representation here one Mount Holyoke woman per 1,000 residents. After Carly’s graduation next year the ratio will, of course, rise even higher.

The question then arose whether other places on the “Left Coast” could boast a similar, relatively high number. Alumnae in Brisbane would be interested in knowing the answer.

— By Anja Salmela Miller ‘56

This article appeared in the fall 2012 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.