Campus Under Quarantine

In the fall of 1918, Mount Holyoke endured the deadliest flu outbreak the world had ever seen

In the weeks before students flocked to campus in the fall of 1918, a deadly strain of influenza reached the shores of Boston with a group of sailors who were docked at the Commonwealth Pier. The College opened its gates to students on September 20, and within three days, ten cases of the flu were reported. Over the next week the number of new cases reported climbed each day. Students complained of sudden high fevers, muscle and joint aches, and chills. Some developed pneumonia. The disease was highly contagious. On September 24, there were thirty-three new cases of the flu on campus. Two days later, there were thirty-one more. Over the course of just a few weeks, more than a quarter of the College’s entire student body of 864 were sickened by the worst influenza outbreak the world had ever seen. The epidemic on campus affected everything from living arrangements to student activities to beloved college traditions.

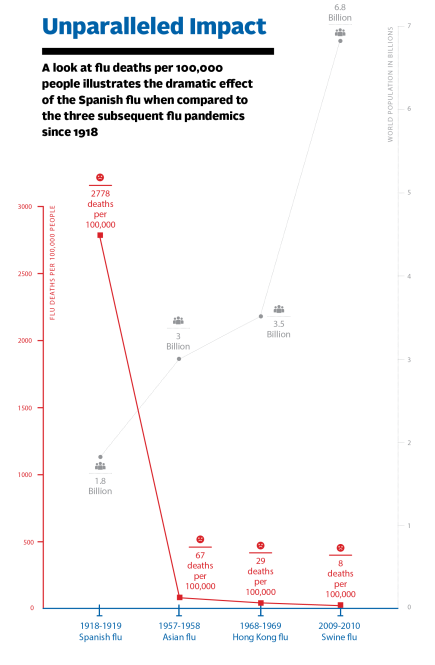

The influenza pandemic of 1918, commonly known as the Spanish Flu, ultimately resulted in death for as much as 5 percent of the world’s population, with estimates ranging from 20 million to 100 million victims in a period of less than two years. While the exact number is difficult to know for certain, experts say that more people died in the 1918 influenza epidemic than died of the bubonic plague or in World War II. One in four people was infected with Spanish Flu and, unlike with most flus that came before and after, the virus struck young adults aggressively, putting college-aged students and young faculty at particular risk. Almost half of all the influenza-related deaths in the outbreak of 1918 occurred in people between the ages of twenty and forty; as many as 8 to 10 percent of all young adults living at the time were killed by the virus.

Adding Sick Wards

The flu in South Hadley resulted in fewer deaths than in other communities across the country, perhaps in part due to the town’s relative geographic isolation. Still, in the first days of the semester, it became apparent that the Everett House infirmary, which was located on the site where the current Reese Psychology and Education building stands, would not be able to hold the rapidly growing population of sick students. Dr. Hooker’s House, located on Park Street, opened as an infirmary on September 25, adding forty more patient beds. At the time, the house was used as faculty housing and was known as Dr. Hooker’s House because it was built for Mount Holyoke botany professor Henrietta Hooker, class of 1873.

Adding a second infirmary was not enough. New reports of influenza among students and faculty emerged so quickly that Brigham Hall, at the time a residence for both students and faculty, was quickly converted into a third emergency hospital. The healthy residents of Brigham were moved to other dorms, and five nurses attended to the steady stream of sick patients. In the Health Services Annual Report for 1918 a nurse wrote, “The Superintendent of Residence Halls worked early and late in the most efficient fashion, ordering many new supplies, and doing the thousand and one things incident to preparing these houses for hospitals.”

The College’s quick reaction to the epidemic, isolating ill patients and quarantining those who may have been exposed, contained the outbreak, which could have devastated the community if left unchecked. Though College records put the total number of reported cases of influenza on campus at 219, many students were not formally treated because there was no room for them in the campus infirmaries. All sick students, even those with a mere hint of a cough or a slightly stuffy nose, were discouraged from attending class. “All classes are about halved by this epidemic,” wrote physics professor Mildred Allen in a letter to her mother. A student from the class of 1920 explained the half-filled classrooms in an October issue of the Mount Holyoke News: “It is almost a habit. Classes seem incidental. If we awake in the morning, feeling unusually sleepy, we decide to stay in bed—at least some people do. We excuse ourselves and the truth is not in us.”

Mountain Day came and the few of us who had not been laid low by the ‘flu’ tramped about while the rest of us, wrapped up in steamer rugs, sat around lackadaisically on back porches with an emaciated, let-me-die look.

Llamarada, class of 1921

Taking it Easy

Faculty understood that attendance would be sparse, but unlike at the surrounding colleges—Smith, Amherst, and UMass—they voted not to cancel classes at Mount Holyoke. At a meeting on October 1, a member of the faculty said, “It would be better to go on with the daily routine with the understanding that the momentum would be less.”

All other student gatherings at the College, including Sunday chapel and daily chapel exercises were canceled until mid-October. President Mary Woolley, about halfway through her tenure as leader of the College, asked the students to use the chapel period “as a time for walks in the open” to ward off the flu. She insisted that “the day, while spent in the open, should not be used as a general picnic day, but should be observed in a quiet and reverent manner,” according to an October 1918 Springfield Republican article titled “God’s Out of Doors.”

Despite the quarantine, the College still held Mountain Day on September 30. In their Llamarada yearbook, members of the class of 1921 recounted, “Mountain Day came and the few of us who had not been laid low by the ‘flu’ tramped about while the rest of us, wrapped up in steamer rugs, sat around lackadaisically on back porches with an emaciated, let-me-die look.”

Because so many students were too ill to climb the mountain in September, a faculty member put forth a motion at a faculty meeting a few weeks later to hold a second Mountain Day. The motion passed, and it was decided that October 17 “be called a holiday and not mountain day in order to eliminate some risk of students taking too-long walks.”

Containing the Threat

The College’s efforts to contain the campus outbreak were quite successful. There had been no new cases reported on campus since the first week in October. And by mid-October the Everett House was, once again, the only infirmary on campus. “Nearly all the girls are back in classes again,” wrote Evelyn Eaton, class of 1919, in an October 13 letter to her mother. “We feel that so far as the immediate college is concerned that we are out of the woods,” Mildred Allen wrote to her mother the same day.

Though vitality had largely been restored, the campus was still under strict quarantine. A notice from the dean’s office, read at lunch on October 22, urged, “Students are not to leave town nor to eat in public places in town. The permission to use the Amherst Trolley was for Mountain Day only.” And, “Friends of students are not to visit or call at the College.” Even the trustees weren’t permitted to come to campus that fall for their annual meeting, and Founder’s Day festivities were reported to be lackluster.

By early November restrictions had been loosened. In a letter dated November 7, Allen noted that students could now have visitors to campus. The following evening, it was arranged for students to go into Holyoke to see the New York Philharmonic. And on November 12, 1918, a day after World War I had officially ended, Mount Holyoke students participated in the city of Holyoke’s armistice parade. The campus quarantine was officially lifted the following day on November 13. Still, the faculty was wary of a second outbreak—as had happened at nearby Amherst College—and students were encouraged not to go home for Thanksgiving if there was “no special reason they should go.”

Remembering the Victims

In South Hadley, the epidemic had not cursed the campus as it had ravaged the rest of the world, where mail piled up at post offices and garbage piled up in the streets because sick workers couldn’t come to work. But even the Field Memorial Gate could not entirely shield Mount Holyoke from the tragic reaches of the global outbreak that wiped out entire families.

“Almost every day we hear of a death of some alumna,” wrote Mildred Allen, “that in spite of the good condition here we realize the seriousness of the whole situation.” Mount Holyoke had survived the flu with one death, a first-year student from southeastern Pennsylvania named Elizabeth M. Smith, class of 1922. A memoriam for Smith was included in the winter issue of the Alumnae Quarterly. “The sadness of her death was very real,” wrote Ethel Barbara Dietrich, professor of economics and sociology, “because we could understand those freshman hopes, because we know something of what her loss means to her father and mother, and because we felt that in her death from influenza and pneumonia Mount Holyoke was paying one of the sacrifices of the war.”

—By Olivia Lammel ’14

Olivia Lammel ’14 is a former editorial assistant at the Alumnae Quarterly and an aspiring writer.

This article appeared in the winter 2015 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

January 18, 2015

always remember that one decent win will wipe out several small loses.

There was a quarantine hospital built at Umass , near the Chancellors .house

This current pandemic of Covid-19 has reminded me of my mother’s occasional comments of the Spanish Flu when she was a student at Smith Colleg from 1917-1921. In 1918 shw became sick with this flue and was placed in an infirmary. She remembers that she felt very ill and the experience in the infirmary was very unpleasant. During my years growing up I do not recall mother having anything like a flu, only perhaps a simple common cold. She was quite healthy all her life and died in 1994, age 94,