MHC Women Behaving Badly: More College Capers

So many capers, so little space in the printed Quarterly. Here are more stories of mischief that we just had to share with you. But if your favorite tale of campus hi-jinks isn’t below, please add it in the comments section.

Men, Men, Men!

Right up until parietals were abolished 1969, students got in trouble for associating with men. In 1850, a seminary teacher wrote about having “dismissed three young ladies, for a violation of the rules of propriety and good order, in connection with receiving calls from gentlemen.” She didn’t elaborate on the offense, but said that, when confronted with the accusation, instead of denying it, they “spread it through the school…with such misrepresentations and false colorings, as to convey the impression that they were going home [being expelled] for a very slight cause.”… Not much had changed when Helen Clark Severinghaus ’27 was restricted to campus for a week after having driven back from Amherst with male friends but without permission.

Founder’s Day Fun

The current tradition of serving students ice cream at Mary Lyon’s grave on Founder’s Day grew out of a joke played in the 1910s by seniors on new students who showed up for that treat when, in fact, no goodies were to be found. For a time in the 1990s, an eggplant appeared on the grave after each Founder’s Day for reasons still unknown.

Imitation: Flattery or Affront?

In the early 1900s, female faculty lived in the dorms and ate with students as well as teaching classes. But one evening, while professors dined elsewhere with the president, students seized the opportunity to lampoon faculty members “in dress, mannerisms, speech, etc,” according to a letter by Sarah Quimby 1907. No doubt the faculty would not have been amused at the caricatures!

BA or MRS?

Fannie Steele was expelled in 1907 because President Mary Woolley discovered that Steele had secretly wed at prom time. Marriage was strictly forbidden for students, so Steele got “a walking ticket” even though it was the last week of classes by the time her secret came to light.

Lots of Blue Marks Against Her

Helen Clark Severinghaus ’27 preserved several dreaded “blue cards” on which were noted students’ rule infractions. Hers included: “failure to register,” driving back from Amherst with men friends, and several counts of getting in late (8:30 p.m. was “late” then.)

Rising to the Occasion

MHC women like to stay on top of things, as these memories attest. Jane B. English ’64 recalls a group of friends and dates making a nighttime climb up the big water tower near the Mandelles for “a neat view of the lights at Westover. We climbed in total darkness. I think I’d have been scared if it had been light and I had been able to look down. As it was, I was only aware of the next rung of the ladder.” Today, the tank has a large fence around it…and MartyChecchi ’01 and friends discovered a secret entrance to the South Mandelle attic that led to the roof. “Those who knew the secret made multiple trips over the next few years and rigged the lock on the main attic door so it wouldn’t lock and we could enjoy the awesome view whenever we wanted.”

Horse Hoopla

Alain H. Dawson ’89 recalls a plan to move a horse skeleton from Clapp Hall to the stables, adding a sign reading “Feed me.” This Halloween stunt was interrupted by campus security guards, who “got quite a surprise to see a horse skull staring back at them,” she says. “We all ran to the nearest dorm party, where we tried to blend in innocently. I believe that after that incident, they bolted down the skeleton.” Kerry M. Mikalchus ’88 writes (presumably tongue in cheek) “I have been advised by my attorney to refrain from commenting on any knowledge I may have regarding the equine relocation attempt. I have also been advised not to comment on any knowledge I may have concerning alleged riding excursions across restricted areas of campus.”

Snow Silliness

Erin K. Purcell ’93 confesses publicly to only one incident: “In the winter of ’89-’90 several Abbey residents decorated cars in the rear parking lot with naughty snow sculptures. I still laugh when I see the pictures.”

Can’t Smithies Spell?

At the direction of a certain senior who shall remain nameless, writes Cara Lee Cookson ’04, a group of Torrey firsties hung a banner in the Smith College library that said, “We go hear cuz we can’t spell Mount Hollyoak.”

Chronicling “Girls Gone Wild”

Incidents in Adrienne Pruitt’s 2005 master’s thesis Girls Gone Wild: Rebellious Behavior of Female Undergraduates 1890–1935 prove that “students did not meekly accept executive decrees, but resisted using mockery, disobedience, and agitation for change.” She notes that “It was not the crimes of femininity in heterosexual sociality that most exercised wardens, nor their prohibition that students most chafed against…Rather it was the crimes of masculinity, of smoking and swaggering and being seen in public without a hat, of behaving too boisterously in the local tea rooms, of claiming for ones self the privileges of mobility, of driving too fast or at all, of disappearing at the drop of a hat for purposes unspecified…those were the offenses which drew the most outcry.”

Look Out Below

Frances “Freddie” Chamberlin Carter ’46 recalls eating breakfast in Wilder at a table that was reserved for faculty during lunch and dinner. “Without a word, Burr [Helen Grumman ’45] put a pat of butter on a napkin, suddenly flipped it and the butter hit the ceiling and stuck there. No doubt it would slowly melt and drip. Burr thinks there have never been so many pranks either before or after our years there. After two years, any prank on campus was automatically blamed on me or credited to me.”

Striking Back with Satire

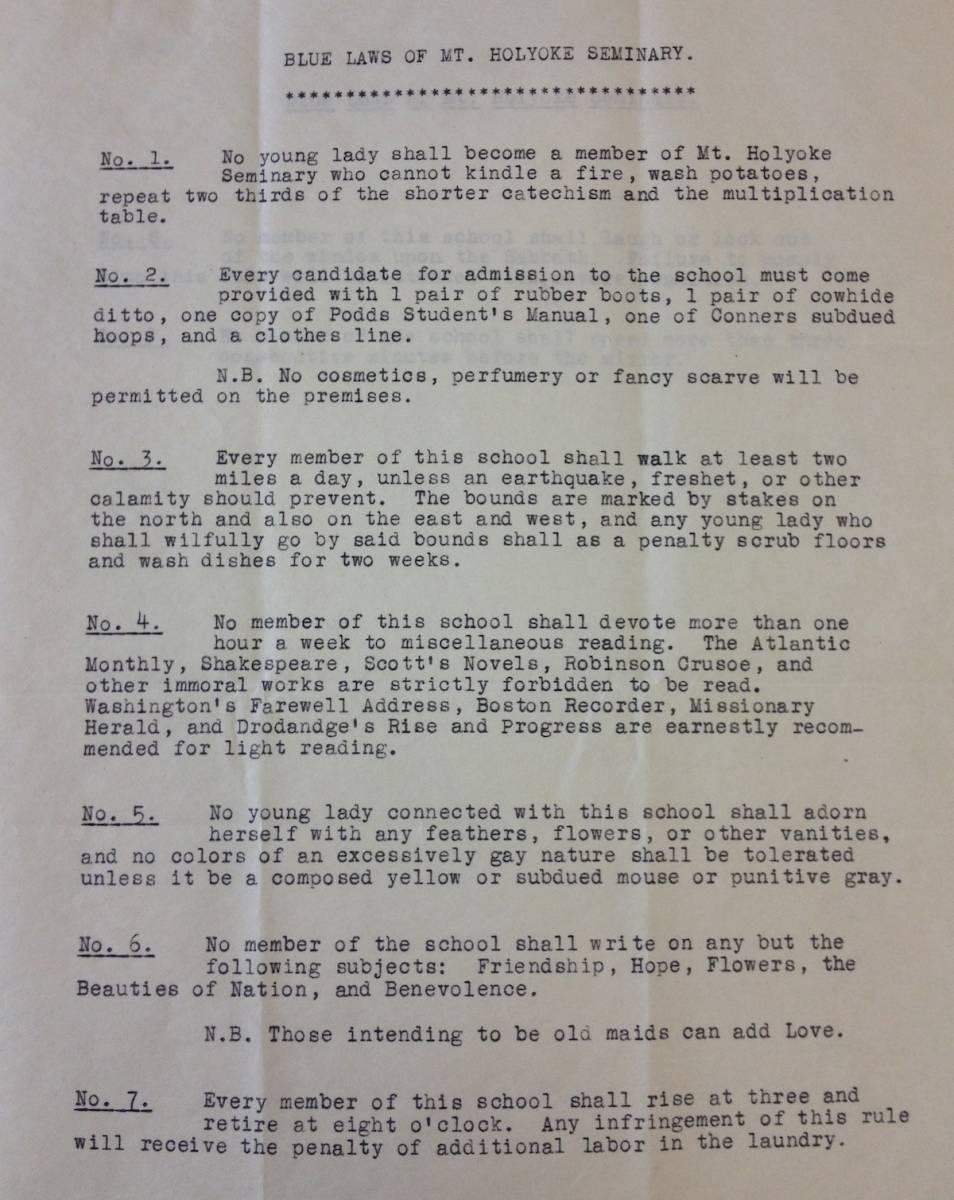

In 1841, all these were forbidden to students on the Sabbath: singing, talking loudly, studying, reading secular books, writing letters, and walking around outside. Reacting to rules they considered ridiculous, students published their own satirical “blue laws,” which were sometimes published as fact in local newspapers (See image below.) One bogus rule instructed each new student to come prepared with “one pair of rubber boots, one pair of cowhide boots, one copy of Podds Students’ Manual, one of Conners subdued hoops, and a clothesline.” Josephine M. Kingsley, 1857, found the real rules oppressive, but wrote that there was “no use protesting against any measure here.” Among her gripes: that students were fined a penny apiece for clothes left on laundry lines.

December 30, 2013

Leave a Reply