Mount Holyoke Alumna Establishes Language Lab in Auroville, India

Mita Radhakrishnan ’90 has built a life and a career in Auroville—a unique and evolving community in India that is dedicated to human unity

On a typical day Mita Radhakrishnan ’90 leaves her eco-historic home in rural India, hops on her moped, and rides less than a mile to work on red earth roads flanked by forest. Seated in front of her is her co-pilot, a white Pomeranian named Foxy. They buzz by palmyra, ficus, and wild date trees fed by seasonal monsoon rains. Minutes later Radhakrishnan rolls up to her two-story office, the new language lab in Auroville, a small town in the southeast of the country. Foxy jumps down and runs into the building, looking for Tapas Desrousseaux, Radhakrishnan’s partner and co-director of the language lab. Radhakrishnan follows, also touches base with Desrousseaux, and, depending on the day, says hello to some combination of children and adults, students and teachers. On a day in early November Radhakrishnan knew she faced a busy schedule: a new Tamil language class starting, testimonials to be finalized for the website, a computer to be repaired, volunteers to be managed, and more.

But even typical days are extraordinary ones for Radhakrishnan. To begin with, Auroville is no ordinary address. Its geography is easy enough to describe—it sits close to Puducherry, a beach town on the Bay of Bengal—but its look and feel are unique in India, if not the world. That’s why Radhakrishnan has been living and working there for more than twenty years.

The Mother’s Vision

Auroville was established in 1968 when roughly 5,000 people from 124 countries gathered near a banyan tree at the center of the would-be township. Representatives of each nation brought with them soil from their homelands to be blended in a lotus-shaped urn. The “City of Dawn,” as Auroville is also known, was founded by a French woman, Mirra Alfassa (a.k.a. “The Mother”). She was inspired by the ideas and ideals of Sri Aurobindo, a Cambridge-educated poet and philosopher. While jailed in India for protesting British colonial rule, Aurobindo described having a mystical experience that, upon his release, led him to abandon politics in pursuit of yoga and spirituality. He felt humans had mastered the outside world but in the process had abandoned their inner development. In Puducherry he established an ashram—a community focused on spiritual realization. After a long-term spiritual partnership, Alfassa took Aurobindo’s vision further to found Auroville as a place where people could live, according to its charter, “above all creeds, all politics, and all nationalities.”

At its core now is the Matrimandir, a ninety-five-foot-high spheroid covered with gold-plated discs. It is a concentration center meant to be the harmonious soul of Auroville. From that center, consciousness is meant to radiate into various zones (residential, cultural, and industrial), which unfurl like bands of celestial bodies in a galaxy. Modest clay homes with thatched roofs intermingle with sleek, futuristic-looking glass structures. Surrounding it all is a green belt that looks to a bird in flight like an oasis surrounded by traditional villages and parched land.

Over the decades, the township has continued to evolve. It’s not a utopia immune from disagreement or instances of crime and discontent, but its focus on social diversity and environmental sustainability (including renewable energy, organic agriculture, and reforestation initiatives) makes it someplace special. During an October 2017 visit to the township, the director general of UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization), Irina Bokova, described Auroville as “a unique place that stands for one humanity united around common values and respect for diversity.” Today roughly 2,800 residents from fifty-four nations call Auroville home.

Tapas Desrousseaux outside the home she shares with Mita Radhakrishnan, who drives a moped to work; the home the two share after a heavy rainfall.

Discovering Auroville

“I fell in love,” Radhakrishnan says. Not with the place, at first, but with the person who brought her there. Radhakrishnan was working in New Delhi in the 1990s when a serious accident left her with a broken collarbone and shoulder blade, and four broken ribs. Desrousseaux suggested Radhakrishnan would convalesce better away from the teeming city and a stressful job. She arrived in Auroville in a wheelchair and, after getting back on her feet, she decided to stay. During her twenty-two years as a resident, Radhakrishnan has become a believer in Auroville’s special mission, and her contributions to the experimental community have been innovative and immense. “I feel like I was lifted up by the scruff of my neck and brought to Auroville because it needed these skills that I have,” she says.

Auroville’s vision—and appeal—remain the same as decades ago. Residents there strive for diversity, unity, spirituality, and utility. Those qualities may initially seem at odds, but for The Mother, like Aurobindo before her, the ideal of human harmony did not mean uniformity. To the contrary, both believed growth from within should be pursued as a law of nature. They encouraged individual development and freedom of thought, because they surmised that diversity is necessary for a community to be complete.

That’s a big part of what appealed to Radhakrishnan about the place. Diversity is the center from which all other values extend. Without it, Aurobindo professed, a society should expect to stagnate or even decline. “It’s so fun, so wonderful, to be able to do that work of bridging those differences—not just differences of race, caste, color, gender, but perspectives,” Radhakrishnan says. In many ways South Hadley was her training ground for that task. “The necessity of looking at different points of view is something that’s instilled in us at Mount Holyoke. . . . You had to see and analyze different perspectives in everything. That’s a really good skill to have, and a lot of who I am and the way I see things was shaped by that. It was totally key.”

Foxy waiting patiently to go home. She arrives at the lab with Radhakrishnan (left) and leaves with Desroussaeux.

Given the deep divides in many societies worldwide, Radhakrishnan believes that valuing diversity has never been more important. “It’s really incredible how one discovers, in this world so taken in by our differences, that we have here a place we’re supposed to go to beyond those differences, go to the soul underneath all of that, to find that oneness,” she says.

That holds for spirituality as well. Radhakrishnan came to Auroville as a self-described atheist, so, at first, she grappled with the spiritual aspects of the community vision. But along the way she discovered that universal religion is not the goal but instead a spiritual presence that, again, insists on freedom and variation. “The goal is to open the way to spirituality beyond religion, to a spirituality that unites everyone,” she says.

Diversity is also integral to the final tenet of Auroville, that of usefulness. In its charter, Auroville is intended to be a place of “unending education” and “constant progress.” Its original vision assumes that residents of this model city will excel individually and as a unit by utilizing their unique abilities for the benefit of all. Radhakrishnan has seen that happen when people who can cook, farm, engineer, build, negotiate, or teach share their talents, whether they have three advanced degrees or none at all. “Whatever you have in your capacity, you have to give it, you have to use it for others,” she says.

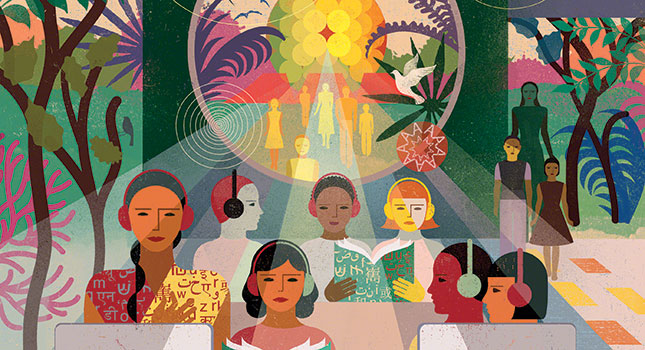

Radhakrishnan has done many different kinds of work to advance that community vision, but it is her work with Desrousseaux in the language lab in Auroville that she is most proud of. Auroville’s universal belief in diversity also extends to education and, specifically, to the study of languages. The value of understanding multiple languages was one of Aurobindo’s teachings. He called language the “sign of the cultural life of a people,” which “enriches its soul in action.” He said, “Diversity of language is worth keeping, because diversity of cultures and differentiation of soul-groups are worth keeping, and because without that diversity life cannot have full play.” The Mother, in particular, considered critical the study of English, French, Sanskrit, and Tamil.

Establishing a Language Lab

When Radhakrishnan came to Auroville, Desrousseaux had already been teaching French out of her home for a few years. After a foray into collective Auroville administration, Radhakrishnan began teaching English and Hindi. In the late 1990s, they started wondering if there was a way to broaden that work, to make it more widely available. “Tapas brought together the language teachers and asked them, can we do something more structured? Can we create a proper language lab for Auroville?” says Radhakrishnan. “Just as Auroville is a city being built following the spiral movement of a galaxy, we wanted to build a language program from the inside out,” she says. They wanted to create a program that would serve their community and the villages beyond it, and to reach out from Auroville to India and the world. In 1998 they wrote their first project proposal, and they received their first grant the next year. They used those funds to buy dictionaries and other supplies for the different languages. Their home remained the organizing center for the larger vision/project until 2003, when Auroville granted them use of a building that had been vacated by its previous occupants. To keep costs down, a local teenager and tech wiz helped them build the lab’s first computer and their first router.

Since then the program has evolved and recently was moved into a newly constructed building in Auroville’s international zone. Radhakrishnan and Desrousseaux had to act as contractors for the sustainably built and operated Auroville Language Lab and Tomatis Research Centre. In the bright, airy language lab and “mediatheque” area, twenty-nine languages are available year-round for study with audio, video, and software resources. Roughly eight languages are also available with live instruction. By pooling ingenuity and expertise, a recently finished recording studio was completed for the equivalent of a few hundred dollars. They are continually trying to manage and grow the program with a small budget and a staff of mainly volunteers. “We have to stretch our rupees in all directions,” she says.

Along the way they’ve received help from other Mount Holyoke alumnae. When Radhakrishnan returned to Auroville from her twenty-fifth reunion her suitcase was jammed with donations of books and games collected by alumnae from neighbors in their respective communities. For her twentieth wedding anniversary, Radhakrishnan’s classmate Mary Picarello Bozza Wise ’90 asked her friends to give money to the language lab, and those donations paid for a hard drive for its main server. Sarvar Kothavala ’92 donated a high-end audio recorder. Other alumnae have shared language materials and expertise. And a project to provide the Tomatis listening training in English for local women was recently accepted to the international crowd-funding charity GlobalGiving, with alumnae making up 54 percent of the donors to the successful campaign. It’s all drawn what Radhakrishnan calls a “circle of love and support” around her work. She hopes to continue widening that loop to include current students as interns at the lab.

Jane Wheeler ’78 has taken a personal and professional interest in Auroville and Radhakrishnan’s work there. Wheeler is associate professor in the College of Business at Bowling Green State University. She’s been to Auroville three times, most recently in December 2017. Wheeler teaches leadership and human behavior and has been studying Auroville’s special brand of collaboration and the role of compassion, trust, and understanding in that society. After her first stay, Wheeler says, “I left wanting to talk about a place and experience that has risen above competition.” She believes that the business environment, like humanity itself, can continue to evolve for the better. “We’re transitional beings,” she says, and “we can help that process” by studying an uncommon place like Auroville.

The language lab in mid-construction; A view of the roof after completion. Radhakrishnan worked as the “go-between” with the engineers and skilled village craftsmen.

The College stays with Radhakrishnan in other ways. “Because of Mount Holyoke I have a very strong wish for justice and a sensitivity to people who are discriminated against. I want to argue for those less fortunate and use my position to do good. It’s been my driving force since MHC,” she says. That translates into her daily work at the language lab in several ways, particularly in her work with children.

Radhakrishnan and Desrousseaux had the life-changing opportunity of meeting with the founders of a field known as “Audio-Psycho-Phonology,” Dr. Alfred Tomatis and his wife, Lena. Their method has applications that address language learning, communication disorders, developmental delays, and learning disorders. Based on Tomatis’s lifetime of research into listening and the ear’s connections to the psyche, nervous system, and brain, the method uses special equipment to exercise the muscles of the middle ear and stimulate the brain in a very particular way. Radhakrishnan has done some of her most gratifying work since incorporating these unique applications of the Tomatis Method into her work.

In the new audio studio Radhakrishnan and her staff were looking forward to helping a mother of a child with learning disabilities to make a recording. “We use the filtered voice of the mother of the child doing the Tomatis program for the child’s treatment, which tends to make the work more effective,” she says. It’s essential for at least one parent to do listening training alongside their child.

“When you work with a child you also have to work with the family. First, we have to help the parents relax, because their own stress and anxiety levels are often high,” Radhakrishnan says. “Then, in some cases, parents of special needs kids can feel disconnected from their children, unable to communicate. They may feel that their child is not fulfilling an ideal, so they may feel bad or embarrassed or find it difficult to accept the child’s disability.

“It’s so sad,” she says. “So, we have to listen to the parents, to affirm them, to strengthen them. We have to tell them that we know it’s hard, but if the parents don’t change their relationship to the child, how will the child grow?” The method itself and the technology go a long way, but what Radhakrishnan calls “the family constellation” must also be in alignment. The Tomatis listening training brings parents and kids into resonance, which helps this process.

On that morning in November with Foxy in tow, Radhakrishnan received an email from the father of a would-be student with severe epilepsy who was falling behind in school. At first the parents didn’t want to participate personally in the child’s training. “I explained to that father why it’s so important for a parent to accompany that child, to come into resonance. A judgmental eye from a parent can affect the self-esteem and increase the anxiety levels of the child,” she says. In that email the father told Radhakrishnan that, in a sharp reversal, both parents had decided to do the program. The news thrilled her. It’s all part of how Radhakrishnan continues to contribute to the visionary community. “We’re here creating something together,” she says. “It’s a privilege to live for a higher ideal.”

—By Heather Baukney Hansen ’94

—Photos courtesy of Mita Radhakrishnan ’90

Heather Baukney Hansen ’94 is an independent journalist who last wrote for the Alumnae Quarterly about Helen Pitts Douglass, class of 1859. Her most recent book is Wildfire: On the Front Lines with Station 8.

This article appeared as “Extraordinary Harmony” in the spring 2018 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

April 18, 2018

Fantastic achievement Mithu!!

Mithu..

Your zeal,dedication and vision are amazing and commendable. What a great job you have been doing….really admirable. May you achieve much more in making Auroville a wonderful place to be in. Kudos to you and your team.

Amazing work Mitu God bless you for what you are doing. May many more homes around benefit from your work and may this infectious zeal be carried forward in the years ahead.