Resiliency in Wartime

The Quarterly takes a look back at student life on campus during World War II—a pivotal time when change was the only constant and students had no choice but to adapt.

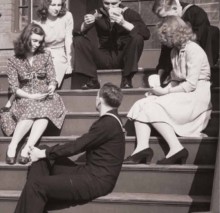

During WWII, US Navy WAVES—Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service—trained on the Mount Holyoke campus before going on to serve the country.

Learning to drink coffee without sugar. Meatless Tuesdays. “Heat cops” closing dorm windows every morning to conserve oil. Saving tin and rubber for reuse. Rolling bandages for the Red Cross.

World War II altered the lives of young women in countless ways. By 1945, the number of women working outside the home had increased by nearly fifty percent, rising to almost twenty million. And during the course of the war, more than 350,000 women joined the US military, serving in official capacities for the first time. But alongside these undeniably sweeping changes, innumerable smaller wartime adjustments occurred as well, especially on the campus of the nation’s oldest women’s college.

Opportunity For Leadership

In 1937 Roswell Ham, the College’s first male president, was inaugurated, much to the disapproval of outgoing president Mary Woolley, who had spent nearly half of her life at the helm of Mount Holyoke during one of its most successful growth periods. Woolley called Ham’s appointment “a blow to the advancement of women,” and his presidency was off to a controversial start.

But by 1942, war response on campus quickly overshadowed Ham’s arrival. That year President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law a new division of the US Navy, and Mount Holyoke became one of the handful of colleges where women came to train.

The newly established Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) was an official part of the Navy, with its members holding the same ranks and ratings as male personnel. In November 1942 the first class of WAVES arrived on campus, many having first participated in basic officer training at Smith College’s US Naval Reserves Midshipmen’s School. At Mount Holyoke, WAVES lived in Rockefeller Hall, renamed the SS Rocky and the Good Ship Rockefeller by students, and trained for service in special military communications. Undergraduates soon were living and learning among the military.

“We had the WAVES taking over a whole dorm. . . and drilling on the campus,” says Miriam (Mimi) Bobrow Raphael ’47, who graduated from high school a year-and-a-half before Pearl Harbor and went on to become a sergeant in the Civil Air Patrol. “We learned to sing the WAVES song in counterpoint to ‘Anchors Aweigh.’”

Raphael and her classmates watched the WAVES “drill on campus and shared the gym locker room with them,” but, she says, “We had little or no social contact. . . It was just a part of our college experience, and, as freshman, we had never known any other.”

- US Marines campus headquarters in 1943

- The original V8s formed in 1942 as a group to accompany a dance number in junior show.

- A Marine is pinned on the bars at a commissioning ceremony on campus.

- Students play cards with Navy officers on leave.

- Women working in a machine shop in Holyoke, Massachusetts.

- Students work in the Mount Holyoke Victory Garden.

- Students collect “waste paper for victory” to be used in shipping supplies to soldiers overseas.

- Students sell war bonds and stamps.

- Students go without maid service.

Over the course of the war more than 10,000 WAVES—or about ten percent of the total number of wartime WAVES trained—went through the programs at Smith and Mount Holyoke before serving across the country in positions including language specialists and radio technicians.

“Free a man to fight” was the slogan of the US Marines Corps women’s reserve, and in March 1943, with the WAVES still occupying the Rockies, the first female Marine recruits arrived. They were on campus for just a short time, consolidating their training programs by the end of the year. Ernestine Stowell ’43, who recalls watching the WAVES and Marines marching drills while she was an undergraduate, enlisted and completed her training on campus. She soon was called to active duty and, after more than 40 years in the Women’s Reserve, retired as a full colonel in 1977.

A War Education

While officers trained in full sight, undergraduate classes continued with the same academic rigor that Mount Holyoke had come to be known for. College faculty and staff altered the curriculum in various ways to accommodate war-related activity, with a new focus on preparing graduates for war production work.

For the first time, students had the opportunity to take classes year-round. Mount Holyoke undergraduates as well as students from more than a dozen other colleges and universities took summer session courses for credit to accelerate their education and graduate as soon as possible in order to join the work force, where they were badly needed. Academic courses were offered across departments, and for the first time students could enroll in new courses specific to wartime training, learning how to build shortwave radios or navigate at night by the stars and studying the economics of war.

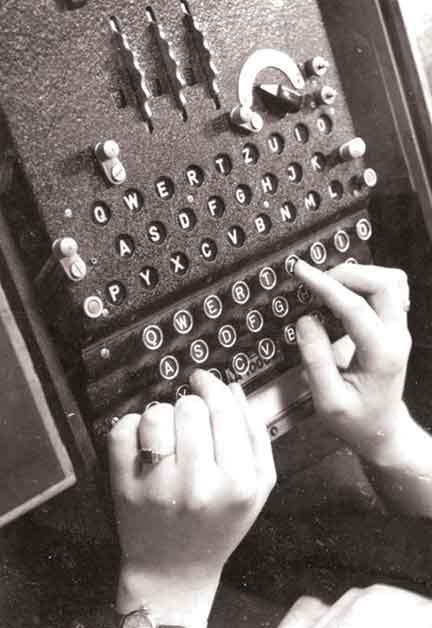

A few specially selected students even learned how to crack code. Professor Roger Holmes taught legendary cryptography courses under the strictest secrecy, demanding that students study behind closed doors. Approved by a faculty unaware of the subject matter, the courses did not exist to the outside world and never appeared in the College catalog. Students who completed the courses were sent directly to Washington, where some went on to help break Japanese code just before the June 1942 Battle of Midway.

Patricia Ryan Leopold ’43 remembers learning that she was selected to take one such secret cryptanalysis course, hearing about it through “markers in [her] post box, to be in a certain building at a certain time, early in the morning and not to tell anybody.” Leopold was also among forty students in her graduating class sworn into the Navy after mastering cryptanalysis at MHC.

“We watched B-24 bombers fly low overhead as their crews trained at nearby Westover Field. When the war ended, civilian flying was restored, and a small group of us formed the Mount Holyoke Flying Club and spent our free time out at LaFleur Field in Northampton to pilot little J-3 Piper Cubs and Aeronca Champions.”

—Miriam (Mimi) Bobrow Raphael ’47

For others, the war meant changing a planned course of study or adapting to unexpected circumstances. Mount Holyoke began offering admission in the winter and summer as well as the fall. Barbara (Bobbie) Scherlis ’46 was one student who entered the College halfway through the 1942-43 academic year as part of the flexible admission program. Having graduated early from high school, she arrived on campus as one of only four January admits. “War was on, and everyone was in a rush,” she says. And entering into an already established class “was not an easy entrance. The class had become organized—friendships were formed.”

Beyond the social hardships, Scherlis realized she could not pursue math as intended because she had missed the first class in a serialized curriculum. “On hearing that no math would be available,” she says, “I was ready to leave. But my mother was there and sent me back to fulfill my admission.”

Scherlis stayed, and to make up her missed credits she enrolled in the College’s new summer program. She took classes she had never considered before, became “hooked into zoology,” and worked. “Instead of physical education,” Scherlis says, “I coached baseball for a group of boys in Holyoke. Their dads were at war, and their moms were working.” She led her team to win the regional championship, “in spite of the fact,” she says, “that I knew little about baseball.” And her team of ten-, eleven-, and twelve-year-old boys taught her “a bit of street education” as a result.

Many Mount Holyoke undergraduates worked in Holyoke factories, where they were taught to operate automatic drill and milling machines to fulfill war contracts. And still others established a Victory Garden—a nine-acre plot of land located behind the athletic fields—for “gym” credit. They grew crops that the College purchased directly, donating the earnings to a number of different wartime causes.

The Little Things

Wartime also meant large-scale charitable efforts on campus and a willingness to sacrifice the small luxuries that previously had been the norm. Maid service for students in the residence halls was eliminated. Students made their own beds, set tables, washed dishes, and cleaned rooms. When it came to housekeeping, as many as 500 students—about half of total enrollment—joined work crews. Many earned twenty to forty-five cents per hour as part of a work-study program, but some volunteered their time as a way to contribute.

A group of undergraduates formed a campus War Service Committee, arranging for toys and clothes to be sent to children overseas. They also organized paper drives, book drives, and blood drives, and they visited soldiers hospitalized at Westover Air Force Base. Members of the student Red Cross organization gathered regularly to roll surgical dressings—20,000 in all. And in March 1944, during a Red Cross drive, students raised more than their goal of $3,000, with eight residence halls achieving 100 percent participation. Students also sewed hundreds of hospital gowns, and the knitters on campus united to knit hundreds of items of clothing, including warm clothes for child evacuees.

Still others offered help in the form of entertainment, most notably the oldest continuing female collegiate a cappella group in the country. In 1942 a group of student singers convened to accompany a dance during junior show. Immediately successful, they named themselves the V8s—after the World War II phrase “V for Victory”—and soon were performing at nearby Westover Air Force Base and, later, at New York City’s Stage Door Canteen, a popular destination for GIs headed off to the war.

In the end, wartime meant immediate and drastic changes, and like everyone at the time, Mount Holyoke women had no choice but to accept these changes and move forward.

“My entire life was during the war years, and so I knew nothing else,” says Scherlis. “Doing homework reading in a canoe on Upper Lake is as good as it gets.”

—By Jennifer Grow ’94

Jennifer Grow ’94 is editor of the Alumnae Quarterly.

This article appeared in the winter 2014 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

January 15, 2014

What a fascinating article. My mother, Betsy Krichbaum ‘43, was one of those WAVES, and by war’s end in 1945 was a full lieutenant, outranking my dad, Navy Lieutenant Junior Grade Edgar McAlister. They married in 1947. Her wartime service remained a great experience and memory.

This article was fascinating! While a student, I studied Math and Women’s Studies so this article hit from both sides! I felt like I knew quite a bit about this time period and women’s roles … but never thought to look into what MHC was doing! The “secret” cryptography courses are fascinating! (And not very surprising to me that MHC alumna were involved with Japanese code-cracking!) I would have loved to have taken them … maybe a J-term class will be offered sometime? 🙂

This article was absolutely fascinating! We all have the early history of MHC down pat, but I, for one, never knew anything about its wartime efforts during the 1940’s. The Quarterly isn’t usually passed on to my daughter to read, but this issue will be. The research is well done and it’s a terrific story – can’t beat that for a good read! BTW, I don’t agree with the commentary denigrating the new look as light-weight.