Sticker Shock

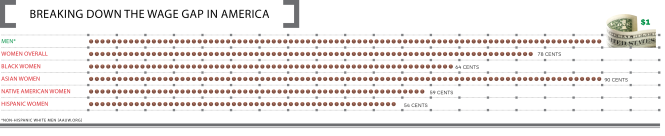

Alumnae navigate a world in which women still earn only seventy-eight cents on the dollar.

Dr. Margaret Fredricks ’00 spent three years searching for a job as a chemist in Germany after earning her doctorate from Technische Universitat Munchen. She worked as a copyeditor for chemistry journals in the meantime. Being a foreigner and a woman were two strikes against her in the job hunt, especially as employers assumed there’d be a language barrier or visas to deal with, she says. After a long search, negotiating for a competitive salary didn’t seem like an option when the offer came for a project-based position as a chemist at a small, German materials technology company.

Fredricks soon knew how much the gap between men’s and women’s earnings was costing her. She spoke to male colleagues and researched the average salary for chemists in Germany. She estimated that men in similar positions earned thousands more—anywhere from 5,000 to 20,000 euros more than she was earning.

Fredricks’ experience is not unique to her career in the sciences or to Germany. The wage gap between men and women has become a hotbed issue globally. The firing of the New York Times’ first female executive editor, Jill Abramson, in May 2014 renewed media and advocacy groups’ focus on the wage gap and gender dynamics in the workplace, as reports suggested that her management style and her complaint about making less than her predecessor led to her dismissal.

Maura Belliveau ’85 offers tips on how to negotiate your salary.

Ongoing Inequity

Growing awareness of the wage gap comes as women play an increasingly critical role in the United States economy and outpace men when it comes to enrolling in college. Women currently make up 47 percent of the US workforce and are increasingly responsible for the financial health of their families. They are the sole or primary source of income in 40 percent of households with children, and married mothers are the primary or co-breadwinners in nearly two-thirds of families, according to the Pew Center for Research.

Women continue to be seen as secondary candidates in the workforce.

A 2012 Yale University study showed that when male and female science faculty were shown identical application materials for a laboratory manager position—with either a male name or a female name attached—they rated the male student as significantly more competent and selected a higher starting salary for him. In the same year, a report from The American Association of University Women (AAUW) found that after accounting for college major, occupation, economic sector, hours worked, months unemployed since graduation, GPA, type of undergraduate institution, selectivity of institution, age, geographical region, and marital status, there was still an unexplained 7 percent difference in male and female college graduates’ earnings one year after graduation.Yet, women make just seventy-eight cents for every dollar a man earns, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. More than five decades ago, in 1963, that figure was fifty-nine cents—indicating relatively slow progress toward closing the gap. A confluence of factors enable the wage gap to remain, experts say. Maternity and family leave can often be major setbacks, and some women’s tendency not to negotiate or to negotiate less aggressively compared to their male counterparts can leave them on uneven footing. Women continue to be seen as secondary candidates in the workforce, and variables such as occupation, college major, and age still don’t account for the disparity between men’s and women’s earnings.

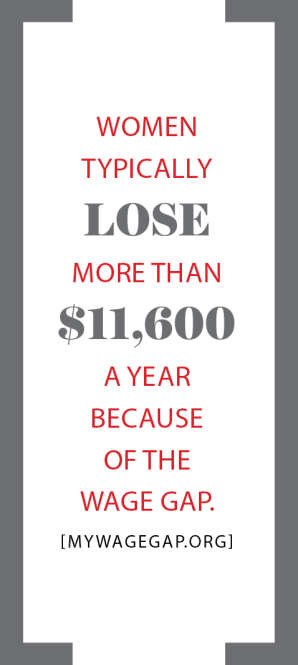

The Wage Gap Costs

“Some people say it’s justified because of the different jobs women and men have, but that’s just baloney,” says New York Democratic Congresswoman Nita Lowey ’59. The wage gap “begins the first year out of college and occurs throughout stages of life.”

Representative Lowey is a cosponsor of the Paycheck Fairness Act, first introduced by Congress in 2009. The act would amend the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 by expanding the scope of the Equal Pay Act of 1963 to “provide more effective remedies to victims of discrimination in the payment of wages on the basis of sex.” Passed by the House of Representatives in 2009, the act was blocked by Republicans in the Senate for the fourth time in September 2014. Lowey says she has seen some improvement in pay equity in the professions since she graduated from Mount Holyoke in 1959, but not enough. “Although we made some progress in the early ’90s, there’s still so much work to do,” she adds. The gender earnings gap narrowed by only 1.7 percentage points between 2004 and 2013, a slower pace than during the previous ten years, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR).

In 2009, President Barack Obama signed his first piece of legislation: the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, which ensures that people can effectively challenge unequal pay. This year, the president issued an executive order that prohibits federal contractors from retaliating against employees who discuss their pay. Despite these advances, the wide divide between men’s and women’s earnings remains a difficult one for many to cross.

“The wage gap has really stagnated for ten years now,” says Ariane Hegewisch, study director at IWPR. IWPR estimates that if the earnings gap continues to narrow at the same rate as it has since 1960, it will take until 2058 for men and women to see equal pay. And several more decades of a pay inequity will do plenty of harm, as women’s lost income translates into less spending power to drive the US economy, which is still in the midst of a slow recovery. The wage gap costs US women who are employed full time, as a group, more than $511 billion every year, according to the National Partnership for Women and Families.

“We know this has real economic consequences for the women workers themselves, but [also] consequences for their children, their communities . . . and the economy,” says Naomi Barry-Perez ’96, director of civil rights at the US Department of Labor. Barry-Perez has spent her entire career focusing on workers’ rights. Now, at the Department of Labor, she walks into the Frances Perkins Building every day and leads a team that works to ensure that job-training programs, unemployment insurance, workers compensation, and other support systems follow nondiscrimination and equal opportunity policies.

Barry-Perez’s department has resolved some pay compensation cases successfully and is now starting to look at the issue more proactively and in a systematic way. “It clearly is an issue of equity. . . . If you’re a woman who’s performing the same or similar work as a man, you should be getting paid the same,” she says.

Speak Up to Earn More

While the wage gap is often associated with higher-power jobs where salary negotiation comes into play, it affects all levels of workers. Female chief executives, for instance, earn only 80 percent of what male CEOs earn, but lower-wage workers are victims as well, and women make up the majority of this segment of the workforce. Women represent 76 percent of workers in the ten lowest-wage jobs, and they suffer a 10 percent wage gap in these occupations, according to Sarita Gupta ’96, executive director of Washington, DC-based Jobs With Justice. “What we see is more and more women joining the low-wage workforce,” Gupta added. Nearly twice as many women as men work in occupations with poverty-level wages, like home health aides, cashiers, and domestic workers, according to IWPR. Not only do these women suffer particularly low wages, especially for tipped workers, but many lose out on benefits when employers don’t offer full-time work.

Click image to enlarge.

Labor experts recommend that women who believe they may be victims of gender-based pay inequity go to their equal employment opportunity or human resources office or speak with a trusted supervisor. Female employees can tell HR they’re concerned their pay may not be in line with their peers and ask for an explanation. They may also use this conversation as an opportunity to ask for a raise or to request that their pay be—at the very least—brought to the same level as their male colleagues in comparable positions.

Margaret Stearns Mansker ’99 is a manager of human resources compliance in the hospitality industry, where she works on a team dedicated to equal employment opportunity and affirmative action issues. In Mansker’s industry, government contractors are subject to government audits to make sure hiring and employment practices are fair to people of all races, genders, and ethnicities. Equal employment opportunity and affirmative action teams, for example, will examine a company’s workforce to make sure it reflects the diversity of the surrounding population and also examine compensation by title to make sure it is fair.

“It’s really tough for women,” she says. “You know you’re not supposed to talk about your salary, and it’s really hard to determine whether it’s because of past experience, your performance, or your gender. It’s one of those times where you really need a strong human resources department.”

Unfinished Business

Unfinished Business

Women need to understand that they are earning less and that there is still work to be done to close the wage gap. As an intern at the nonprofit MotherWoman in Hadley, Massachusetts, Leigh Edwards ’14 organized an Equal Pay Day in nearby Northampton to raise awareness this past April. For her, the experience proved an opportunity to discover that policy changes in other areas could make a big difference in putting women on equal footing in the workplace. “We found that the wage gap [would be] mitigated if women had adequate paid sick leave and better child care,” she says. But before there are major policy changes in the US or elsewhere, the next step for women is to aggressively research pay levels for jobs they want, negotiate harder, and share their stories publicly and with other women, experts say.

And that’s exactly what chemist Margaret Fredricks ’00 ultimately did. Last summer, when she learned that her contract job would be extended through to the end of the project, she found the confidence to ask for more money—and got it. She knew that she had become invaluable to the project, and that opened a window to ask for more money. She set a hard and fast minimum annual salary requirement and made it clear she was willing to leave the job if the company’s offer fell short. Fredricks surprised herself: “For [a difference of] 1,000 euros, I was willing to walk out of the company,” she says. “I never really thought I would be the type to be able to do something like that.”

She now makes 10,000 more euros a year than she did just a few months ago. And while she’s proud of herself, saying, “Now I feel like I’m getting closer to what I’m worth,” she knows she needs to continue improving her negotiating skills. In the future Fredricks plans to set a higher bar for the minimum salary she’s willing to accept, and she will certainly negotiate. But for now, she’s satisfied.

—By Erin McCarthy ’06

Erin McCarthy ’06 is a writer and journalist based in New York.

This article appeared in the fall 2014 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

October 15, 2014

I am the proud father of two MoHo graduates, Alix ’00 and Anne-Gabrielle ’13.

I strongly disagree when Erin quotes Margaret Stearns Mansker ’99 as saying ‘You know you are not supposed to talk about your salary’. Of course you are allowed to speak about your salary and in fact writing or telling you it’s not allowed is illegal and in breach of the very basic protection of organizing spelled out by Federal Law. If this is part of any company policy you can complain to your local National Labor Relations Board and they will investigate and have this changed.

I know because that’s exactly what we recently did with Lionbridge Technologies, a Microsoft’s contractor that tried, like so many companies to prevent its employees to compare their compensation and find out they are discriminated against, which is of course another breach of the law. The problem is most employees seem to ignore the law or are afraid to use it to complain. We used it and also realized trying to negotiate individually would only lead us so far. Therefore the basic advice I would give and that is missing from this article is ‘organize’, create unions as so many women did who brought us the 8 hour workday, the week-end etc. Don’t choose to fight this injustice only on an individual basis by better negotiating for yourself. Organize and negotiate collectively. Best wishes.

Philippe