Pathfinders in Public Health

Alumnae Break New Ground Preventing Disease and Promoting Health

The public health challenges of the twenty-first century are vast—antibiotic resistance is on the rise, childhood obesity is rampant, and nearly fifty million Americans are still without health care. Add the effects of global warming, cholera outbreaks in Africa, and the continuing HIV/ AIDS pandemic and these combined hurdles seem overwhelming, possibly insurmountable. Fortunately, Mount Holyoke alumnae are making significant strides in public health by founding innovative community-health organizations, launching national wellness initiatives, and collaborating with communities in Zimbabwe to stanch the cholera epidemic, to name just a few.

Deborah Klein Walker ’65, EdD

Deborah Klein Walker ’65, EdD

Title: Vice president and principal associate at Abt Associates, a public health consulting firm; former president of the American Public Health Association

Thirty years ago—when she was working at the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare—Deborah Klein Walker didn’t even know what public health was. Today, she’s a nationally respected

public health expert known for her leadership on maternal- and child-health issues as well as substance abuse programs. She discovered public health while teaching community child-health studies at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and “never looked back.”

During her fifteen years at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Walker helped reduce the infant mortality rate. In fact, during her tenure, Massachusetts became the state with the lowest infant-mortality rate. (It also had one of the lowest teen-pregnancy rates.)

Now, at Boston consulting firm Abt Associates, she is the principal investigator in the company’s domestic health division, where she juggles four to five projects at once. In addition to evaluating federal programs such as Healthy Start, she and her team help government agencies devise strategies to make programs more effective.

One of the most exciting tasks before her now is advising the Maternal and Child Health Bureau on how to improve its Healthy Start programs around the country, specifically strengthening “interconception” care for women—covering the period between births. (Currently, Medicaid only covers a poor woman during her pregnancy and for one postpartum visit; then she falls out of the system unless she gets pregnant again.) Though Walker has just begun designing her approach, it will include linking women to needed services such as family planning, mental health, and counseling; encouraging insurers to cover health visits; and educating women to take folic acid for the prevention of spina bifida.

Walker is also leading a five-year evaluation of a new Department of Health and Human Services program that’s geared toward improving healthy child development in six states across the country. Among other things, it will provide home visits, parent support, and development screening in primary-care offices—services that are not covered by Medicaid.

Deborah Walker, shown here (back row, center) visiting a clinic in Uganda, says she’s in public health because it is “the practice of social justice.”

Though she loves her work at Abt Associates, Walker says there’s nothing like working in the government sector, where people are driven by the same social mission to improve others’ lives. “Public health is there to assure the health of everyone. And only the government entity has that mandate,” she says. “You can do all you want from the private sector, but you’re still not responsible for every single person in that community.”

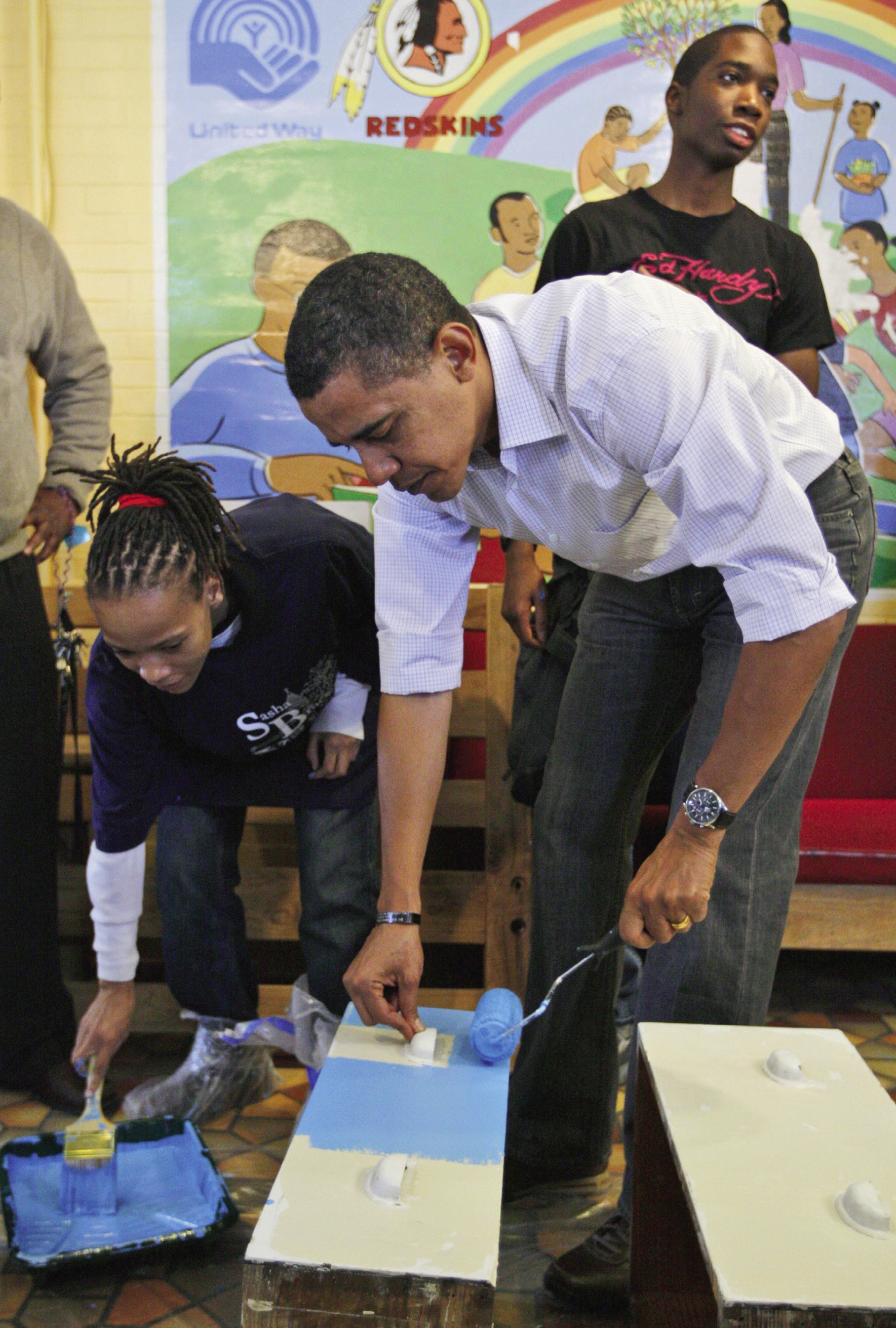

What would you ask President Obama to do for public health?

Address prevention. “A lot of people say ‘prevention,’ but they mean, ‘let’s help this person who came to my office be healthy.’ I mean it on a bigger level—you have to have support in the community and address all the social determinants of health. You make sure that kids have a safe way to walk to school, which addresses the obesity epidemic. You make sure the price of tobacco is high so kids don’t smoke.”

Heidi L. Behforouz ’90, MD

Heidi L. Behforouz ’90, MD

Title: Founder and executive director of Prevention and Access to Care and Treatment, which serves Boston’s sickest and most marginalized AIDS patients

Major at MHC: Biochemistry

One of the trickiest things about running a public health project is proving that it works. Prevention and Access to Care and Treatment (PACT), which Behforouz founded in 1997, is rare in that it shows measurable results.

Using a standardized model of intervention, PACT-trained community health workers help inner-city AIDS patients, usually black or Latino, visiting them daily to make sure they take their meds and accompanying them to doctor’s visits. These are disenfranchised patients—many of whom are also burdened with other problems such as abusive relationships, substance abuse, and depression—who, despite having had conventional case managers in the past, are sick and dying. PACT community health workers go a step further, forming a surrogate support network for the patient. “There is power [in] knowing the context of the person’s life,” says Behforouz.

Having a health advocate pays off: 75 percent of PACT patients improve dramatically, according to internal data that Behforouz and her team collected. But what really sets PACT apart—and why it’s being replicated by other US cities (including Baltimore, New York, and Miami) and even in Peru—is a twenty-five-point curriculum (including written modules and a patient workbook) that staff and patient work on together. The curriculum covers topics such as how to take antiretroviral medications, know what both a CD4 count and a viral load are, and how to schedule and prepare for appointments.

Behforouz has also been asked to adapt the PACT model for other chronic diseases, such as diabetes, that disproportionately affect the poor.

What would you ask President Obama to do for public health?

Integrate community health workers into the medical system. “They are a critical piece of the puzzle. They are underutilized and need training, support, living wages, standardized interventions, and people to measure their impact.”

Kayla Jackson ’86, MPA (master’s in public administration)

Title: Vice president for programs at the National Network for Youth in Washington, DC

Major at MHC: English

“I always say my goal is to not have a job to come to,” says Kayla Jackson, vice president for programs at the National Network for Youth (NNY), the national membership association for community-based runaway and homeless youth organizations. Primarily an advocacy organization, NNY supports policies and legislation—such as the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act—that give federal funding to homeless youth groups.

Jackson’s main role at NNY is running a Centers for Disease Control (CDC)–funded HIV prevention program called Street Smart, which specifically targets runaway and homeless youth. “Oftentimes you’re telling kids, ‘Delay having sex. Only have sex with someone who you are committed to and whose HIV status you know,’” says Jackson. “Then you look at street kids who trade sex for money, shelter, food, and drugs. When it becomes part of the street economy, your choices narrow. You have to look at HIV prevention in a completely different context.”

In addition to developing the curriculum for Street Smart, to help prevent HIV and substance abuse, Jackson has also begun training members across the country—so they can, in turn, train youth workers in their organizations to prevent HIV among runaways. During fifteen group meetings and one private counseling session, Street Smart teaches kids coping and negotiation skills, HIV/AIDS harm reduction, and how to identify personal triggers.

She’s also working to bridge the gap between members (who tend to keep a low profile, since most people don’t like knowing there’s a homeless shelter on their block) and schools, state homeless coordinators, and state health agencies—all of whom want to learn how to reach homeless youth better. Though homeless and runaway youth total an estimated 2.5 million in the United States, this population is virtually invisible, according to Jackson. “You ask most people where the homeless youth gather in their area, and they’re not able to tell you.”

What would you ask President Obama to do for public health?

Fund prevention initiatives across the board. “Prevention in this country is cut consistently. We spend so much money on treating disease, which is so much more expensive. But if you fund prevention—and you truly allow everyone access to appropriate preventive health care—that would save so much money.”

Michelle Chuk ’95, MPH

Title: Senior adviser at the National Association for County and City Health Officials

Major at MHC: Biology and anthropology

Improving the health of all Americans is a lofty goal, but that’s exactly what Michelle Chuk has taken on by helping to lead her organization’s Alliance to Make US Healthiest (www.healthiestnation.org) initiative. NACCHO, a coalition of nearly 2,800 local US health departments, began this collaborative effort last year after conversations with the CDC and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials about how to improve health outcomes in the United States.

“We started talking about what other sectors…are critically important in improving overall health status,” says Chuk. “We decided it was everybody: business has a role to play, education has its role to play, community organizations have a role to play, medical care has its own role to play.”

The Alliance to Make US Healthiest (AMH) uses a “bottom up” approach—it hopes to encourage individuals to be more proactive about their health, and about demanding access to infrastructure (such as bike lanes, sidewalks, and healthier food at public schools) that encourages healthy

behavior. AMH also serves as a clearinghouse of information—providing educational resources to community groups and activists, and linking members so they can share advice, materials, and know-how.

Last year, after a big hepatitis C outbreak in Nevada, Chuk helped connect the Hepatitis Foundation International (a member of AMH) with a small Nevadabased organization that was seeking guidance on educating community members about hepatitis C. Because the Hepatitis Foundation was having a

conference in Las Vegas, it was able to share its resources with the local organization at very little added cost. So far, Chuk and her team have secured as members more than 200 organizations (including Planned Parenthood, Target, and the American Heart Association) and 800 individuals.

“We’re trying to build a grassroots momentum,” says Chuk. “Health should be an aspect of all policies, not just ‘health and medicine’ policies.”

What would you ask President Obama to do for public health?

Improve public health, not just health care. “Many of today’s most pressing domestic challenges can be addressed by improving public health. If you can make communities healthier overall, you will not only have healthier people. You will also have better outcomes in education, a better ability to address issues around public safety and security, a healthier workforce, more robust communities, and a healthier and more productive society.”

Miriam Aschkenasy ’94, MD, MPH

Title: Public health specialist at Oxfam; works three emergency room shifts a month at Cambridge Hospital in Boston

Major at MHC: Biochemistry

Trained as an emergency medicine physician, Aschkenasy had an epiphany while in her second year of residency, in Kathmandu. “It just completely transformed me,” says Aschkenasy, who realized in Nepal that public health was the only way to help those who couldn’t reach the system on their own. She went on to earn her master’s in public health at Harvard, where she simultaneously completed a fellowship in international emergency medicine and public health.

Aschkenasy was assessing the environmental public health effects of Hurricane Katrina as a consultant for Oxfam when the agency advertised for its first public health specialist. She applied for the job, and in 2006, was hired to head the organization’s new public health initiative. Today, she works with Oxfam’s six regional offices, including Zimbabwe, where Oxfam is tackling the cholera epidemic by mapping faulty drinking water sources with GPS and working with local partners to repair them. They’re also conducting public health and hygiene education, launching a community-based early-warning diarrhea surveillance system, and supplying oral rehydration solution to help treat cholera patients.

“Direct critical care is great, but it’s like spitting in the ocean. When you do international public heal

th, it’s still an ocean, but you’re throwing a whole bucket in there.”

What would you ask President Obama to do for public health?

Cap malpractice awards. “Doctors do so much excessive testing out of fear of litigation. Capping

malpractice would immediately reduce the cost of health care for everybody. There is no way to fix the current health care crisis without this being an aspect of it.”

A Brief History of Public Health

In 1854, a British physician named Dr. John Snow identified the source of a London cholera epidemic—a public well located just feet from an old cesspit.

Snow is one of the fathers of modern-day public health, the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting healthy behaviors. Proper sanitation is just one of the public health achievements of the twentieth century. Others include immunization programs, family planning services, and motor-vehicle-safety laws (mandating the use of seatbelts, child-safety seats, and motorcycle helmets.)

Today, leaders such as New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg have picked up where Dr. Snow left off, launching public health campaigns to ban smoking in bars and restaurants, outlawing transfats in restaurants, and requiring chain eateries to post calorie counts for all menu items.

—By Hannah Wallace ’95

Hannah Wallace ’95 is a Brooklyn-based journalist and the senior editor at JANERA.com, an online magazine for global nomads. This article appeared in the spring 2009 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

Learn More: See links below to our alumnae’s organizations and more information about public health.

• Abt Associates:

Founded in 1965, the employee-owned research and consulting firm Abt Associates offers its expertise in international health and technical assistance to governments, nonprofits, and private organizations. Abt works in more than forty countries to promote public health.

The company’s Web site provides detailed information about their markets, projects, and conferences. The Web site also includes extensive health information on some of the topics they address on an international scale, such as addiction treatment and prevention, HIV/AIDS, midwifery, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

• Prevention and Access to Care and Treatment (PACT):

Prevention and Access to Care and Treatment (PACT) is a community-based domestic healthcare program serving the Boston area. PACT provides home visits to HIV patients who are very ill or members of marginalized communities and outreach programs. PACT volunteers help patients maintain a strict medication schedule, attend doctor’s appointments, and receive adequate nutrition. The organization draws volunteers from at-risk communities and provides training to help them become prevention and harm reduction leaders. For photos, contact info., and volunteer opportunities, click here.

• Oxfam:

Oxfam America works with groups in more than 100 countries to combat poverty and injustice. They respond to natural disasters and emergencies, aid farmers worldwide in developing sustainable agriculture, and promote equal rights for women around the world. Oxfam America also advocates the reformation of US foreign aid to be able to reach people in the greatest need. Oxfam is involved in making available expensive and important medicines to people in need around the world. For information on the history of Oxfam, volunteer opportunities, video clips, and downloadable guides, click here.

Visit Oxfam’s Web site to view images of, and read about, Oxfam’s work fighting the cholera epidemic in Zimbabwe.

• National Network for Youth:

The National Network for Youth (NN4Y) reaches out to homeless, runaway, or otherwise disconnected youth and works to provide them with creative outlets, educational opportunities, and mentoring relationships. NN4Y also works within federal and state government to ensure that legislation affecting kids is protected. The organization is taking steps to inform youth about the risks of HIV infection and other health problems. Visit NN4Y’s Web site to read youth testimonies, download fact sheets, and get information on how to become a youth advocate.

• Alliance to Make US Healthiest:

The Alliance to Make US Healthiest works to ensure that public health promotion is prioritized within the nation through collaborating with other programs and reaching out to communities. The Alliance provides a scorecard of the US health system, comparing 2008’s information with that from 2006 (the results may surprise you!) Visit the organization’s Web site for information on becoming a member, video clips, and a schedule of events.

• There’s lots more information on public health at the National Institutes of Health Web site.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is a federal agency that supports medical research. The NIH was involved in medical achievements such as the sequencing of the human genome, the discovery of new cancer treatments, and the control of infectious diseases. Visit the Institute’s Web site for photo galleries, information about clinical trials, and Health Hotline phone numbers for information on alternative medicine, weight control, and drug abuse, to name a few.

Financial Challenges: What MHC Is Up Against

Since a “perfect storm” swept the US economy off its foundations last fall, the waves have eroded finances everywhere, including at Mount Holyoke. As President Joanne V. Creighton wrote to the campus community in January, “In the past six months we have seen the financial markets move from shaky to steeply lower and the economy as a whole move from weakness to serious recession.”

Since a “perfect storm” swept the US economy off its foundations last fall, the waves have eroded finances everywhere, including at Mount Holyoke. As President Joanne V. Creighton wrote to the campus community in January, “In the past six months we have seen the financial markets move from shaky to steeply lower and the economy as a whole move from weakness to serious recession.”

“The consensus view among financial experts is that the worst may not yet be over and that the recovery will be long and slow. The negative impact on Mount Holyoke and on higher education in general is already being felt, and it will continue well into the future. As a result, like many other institutions, the college needs to make both short term and longer-term changes to remain financially stable.”

MHC’s endowment—the income from this fund accounts for about one-fifth of each year’s operating budget— dropped by $155 million in the last half of 2008. But Mount Holyoke is hardly alone in being hammered by the recession. A national survey released in late January noted that American college and university endowments lost an average of 23 percent during fall 2008. “This is the most challenging environment that any of us in higher education have seen in our professional lifetimes,” Molly Broad, president of the American Council on Education, told the Washington Post in January.

This is true even though higher education’s endowments generally outperformed the market during the fall slide. For example, the S&P 500 index dropped nearly 29 percent during the second half of 2008, while MHC’s endowment value slid 22 percent during this period.

And Mount Holyoke’s situation is far better than that of many. Our endowment’s market value ranks among the top 115 nationally, and the current financial trouble comes after years of extraordinarily good returns due to prudent investment of our endowment funds.

Still, budget gaps are significant across the education spectrum. To fill them, institutions are considering or implementing various combinations of steep spending cuts, hiring freezes, layoffs, tuition hikes, and increasing the amount drawn from the endowment for current spending needs.

In the article that follows, President Creighton details how the college is stewarding its finances to preserve core values while weathering the financial storm.—Emily Harrison Weir

President Creighton Lays Out MHC’s Budget Strategies

President Creighton Lays Out MHC’s Budget Strategies

Mount Holyoke is fortunate to have entered the economic downturn in a position of strength, with giving and endowment levels at all-time highs last year, important campus projects like the new residence hall and outdoor athletic facilities already completed, and our $300 million campaign well past its midway point. As the recession has worsened, however, the college faces intensified financial challenges.

Our revenue comes primarily from three sources: about 63 percent from tuition, room, and board (minus financial aid); 17 percent from Annual Fund gifts and grants; and 20 percent from endowment income. This year, primarily because of increased financial aid costs and decreased gift giving, we are projecting a budget deficit of $2 million, a gap we are working to close through a variety of measures.

While at press time for the Quarterly it is too early to know any definitive numbers for 2009–10, we do have some “leading indicators.” In admissions, our application total to date is slightly lower than last year’s, but still well over 3,000, resulting in the third highest number of applications in the history of the college. This is a positive sign in light of the uncertain economy and the sudden declines a number of peer institutions have experienced. Still, we won’t have a sense of what the class of 2013 will look like until April or May. We do know that families are feeling great financial pressure, which we anticipate will affect requests for financial aid and our ultimate enrollment.

In development, this year’s Annual Fund is currently 14 percent behind last year’s record-setting performance, and we may fall considerably short of our $8.8 million goal.

The endowment performed very well in FY2008 and reached a level of almost $660 million. It dropped to just over $500 million as of December 31, 2008. While this reduction will have a significant impact on the budget over time, the 2009–10 budget will not be negatively affected since our spending policy uses a three-year average market value.

The senior college staff and I, in close consultation with divisions and departments, have been forecasting, reviewing, and adjusting institutional expenses while doing our best to anticipate revenues. With so many variables on both the expense and revenue sides (besides fall 2009 enrollment, health insurance rates, and energy costs, for example), budgeting is an iterative process. Let me articulate what I believe must be our guiding principles as we proceed:

• We must maintain the academic strength of Mount Holyoke College, now and for future generations.

• We must be sensitive to the needs of all members of our community, but particularly of those who may be the most financially vulnerable in the current economic climate.

• We must look for efficiencies through greater cooperation and restructuring of our work.

• We must understand that these are unusual times, and we may employ temporary, unusual actions that might not be sustainable in the long run.

• We must, if the financial situation worsens over the course of the next year, take an even harder look at cost-cutting and revenue-enhancing opportunities.

The resourceful and tireless work of our dedicated corps of staff and volunteers is making a positive difference in our efforts. The faculty and student planning and budget committees have been meeting regularly with Mary Jo Maydew, the college’s vice president for finance and administration. In addition, open campuswide budget forums have been held, suggestions have been solicited actively and compiled on the Web, and Mary Jo is providing regular online updates to review our progress toward a final budget and to address issues of community interest.

Of course, the buck stops with the senior administration, who will finalize the budget in mid- April, and with the Board of Trustees, who will be asked to approve the fiscal 2010 budget at their May meeting and who have ultimate responsibility for the fiscal welfare of the institution. While as of this writing, it is still too early to make firm decisions about items in the budget, here is a summary of our thinking on several key areas of special interest to alumnae.

• Salaries: It seems likely that salary increases this year will need to be minimal or nonexistent. We have received many compelling ideas from faculty, staff, and trustees alike about how to weight any salary increases toward lower-paid employees. We hope to avoid salary reductions, since we do need to consider the long-term competitiveness of our salary structures.

• Positions: Our goal is to minimize layoffs, although we are not confident that they can be avoid

ed entirely. We are working diligently to make the most of every position vacancy, including those that might occur through voluntary retirements or reductions in schedule.

• General spending: From the many communications to me and other college leaders, there is clearly a desire on the part of the community to be careful and frugal in our expenditures: fewer entertainment events, fewer paid-for meals, less paper, more electronic communication, etc.

• Revenue enhancement: We are looking for opportunities for improving revenues, as we have with the recent expansion of our postbaccalaureate program. These include the active exploration of Five College certificate programs, more outside use of our conference center, and other Five College initiatives.

While we will have to make changes and find economies, be assured that we will do our utmost to protect our commitment to meeting the full, demonstrated financial need of students. We will also do all we can to preserve the quality and character of a Mount Holyoke education. As I have said before, I have enormous confidence in our ability to work together through difficult times to sustain this wonderful institution.

As we move through this difficult financial period, I will keep you informed about how the college is faring and the strategies we use to ensure its long-term ability to fulfill its vital function in the world.

Sincerely,

Joanne V. Creighton

Alumnae Association President Davis: “MHC Needs Your Help”

Alumnae Association President Davis: “MHC Needs Your Help”

There is no other way to say it: Mount Holyoke needs your help, and needs it now. The current financial downturn is affecting every college in the nation, and MHC is not immune. Families’ circumstances are changing, and current students need more financial aid—in some cases, a great deal more.

It is a rare occasion when the Alumnae Association directly asks alums for help. We wholeheartedly support the college, but our mission is, and always has been, supporting alumnae. In times like these, though, the college’s well-being must be our concern, too. Mount Holyoke is, in large part, its alumnae, and we can make a difference. Recall the green velvet purse Mary Lyon used to collect contributions to fund our college. Please, if you can, help your alma mater in this time of need. If a dollar is all you can spare, send it. Your generosity not only advances the college’s excellence in the liberal arts, but also helps a current student continue to receive it.

In the spirit of Mary Lyon, our deepest thanks for your support.

Mary Graham Davis ’65

Contribute to MHC online. Go to mtholyoke.edu/go/mhcgive

This article appeared in the spring 2009 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

Humble Crusader: Tashi Zangmo FP’99 Promotes Female Education in Bhutan

Girls never went to school when Tashi Zangmo FP’99 was growing up in a remote corner of Bhutan. She’s working to change that. (Photo by Ben Barnhart)

When Zangmo was growing up in one of the most remote corners of mountainous Bhutan, she says, “girls never went to school.” She was the first girl ever sent to school from her community. Her father was a community spiritual teacher, but her mother was illiterate, and Zangmo recalls the decision to send her to school as “a big leap for my mother and me. The only school was a one-day walk from my village,” so the nine-year-old Zangmo left her family and moved there. “I had to room with boys, the teachers weren’t used to working with young girls … it was a horrible experience, but that’s not important,” Zangmo says.

What is key is that those early classroom days inspired the adult Zangmo to help other girls have a better experience than she had. “Even when I was making hardly enough money to feed myself, there was a vision that I could do something down the road to help girls get a better education in communities similar to mine. I want to be a role model,” she says.

At first, Zangmo envisioned just helping her seven siblings, but as her own education progressed, she says, “my vision grew from family to community, and now I think of how I can serve my country best.”

Although Zangmo humbly deflects credit for her ideas, her goal is nothing short of changing Bhutanese society by improving girls’ education. After receiving her doctorate from UMass–Amherst this past December, she moved back to her homeland and founded the Bhutan Nuns Foundation, under the patronage of Queen Ashi Tshering Yangdon Wangchuck.

To grasp why supporting nuns’ education also means educating girls generally, it helps to understand evolving Bhutanese beliefs about girls and education.

A 2002 estimate by UNESCO held that twice as many boys as girls attend school in Bhutan, putting the rate of girls in school at just 10 percent. Since then, access to primary education has been a royal priority. According to UNICEF, the number of students has more than doubled since 1990, and girls’ enrollment is expanding steadily. However, significant gender gaps remain in practice. Often, students still must travel considerable distances to find a school, and tradition holds that girls and women should stay near their families.

Zangmo’s plan? Since you can’t easily bring all girls to a school, take schools to the girls. With Buddhist nunneries in many rural locations that lack schools, that’s where her efforts are focused. Nunnery-based education also has the advantage of being free. (Government-run schools require families to pay for uniforms and supplies. This makes schooling beyond the reach of many, especially families with numerous children.) And working with nuns seemed natural to Zangmo, a practicing Buddhist who says she comes from “a very spiritual family.”

“Nunneries [already] provide women from all walks of life with an educational opportunity that has no age or learning capacity limit, as the formal education sector does,” she explains. “If the nunneries provided good education, nuns and other girls and women coming to the nunneries would be empowered and be in a better position to contribute to their communities,” Zangmo reasons. “Nuns in turn could become teachers and social workers within their villages and their nunneries, and contribute to the larger national development goal of raising ‘Gross National Happiness.’”

The problem is that nunneries, while often one of few alternative educational institutions open to females, typically provide a very poor learning environment, Zangmo says. “In some, there is no electricity, no bathrooms, no curriculum, no qualified teachers—nothing.” Still, it’s often the only game in town, so there are about five times as many girls seeking admission as there are openings, Zangmo estimates. Sadly, those admitted are likely to gain little academic substance from the country’s 800 to 900 nuns. “It breaks my heart to have families send their children there with the hope of learning only to discover that there are no learning facilities,” she says. “But something can be done. My vision is to give the nuns teacher training.”

And the first glimmers of this vision took shape at Mount Holyoke, where Mary Lyon’s goal was similar. “I had no clue what Mount Holyoke College was all about when I applied,” Zangmo admits. “But I read Mary Lyon’s book, and it really spoke to my heart. Professor Penny Gill used to say, ‘Mary Lyon calls you,’ and that helped me articulate my vision.”

Tashi Zangmo FP’99 visits with young nuns in Southeastern Bhutan duringa 2007 research trip. She hopes to train nuns to teach other girls inthis modernizing country. (At MHC she was a special major in developmental studies.)

Zangmo started helping the nuns back home more effectively during her time at MHC. Babysitting earnings bought clothing and better drinking water for the nuns in her native village. She used a $10,000 Samuel Huntington Public Service Award to start a small library there, and Zangmo spent about two years teaching adult literacy classes in Bhutan after her graduation. In 2005, the minister of home and cultural affairs in Bhutan heard of Zangmo’s efforts, and asked her to propose a systematic way to improve girls’ lot. She brought him a proposal on notebook paper and, with the minister’s support, came up with the beginnings of the Bhutan Nuns Foundation.

Back in the US for her PhD work, Zangmo formed an advisory group and raised seed money for the foundation. She launched it officially this winter by moving back to Bhutan, opening an office, and hiring a coworker. “There is a lot to be done!” she says, reciting a litany of goals that include improving nuns’ living conditions, building a structured curriculum, training nuns to teach both at the nunneries and in the public school system, and creating a higher-learning center open to all women.

“Ten years from now, I envision that the foundation will have improved the lives not only of the nuns but also of every girl and woman in Bhutan,” she says.

There was no such help when Zangmo wanted to further her own education. After high school

-level studies, Zangmo knew that, in Bhutan, “unless I became a nun, there was no opportunity for me to do further Buddhist studies.” She had to break with tradition, earning money in a secretarial job for the government, then leaving her family and moving to India, where she studied Buddhist philosophy. “My family said, ‘Why would you leave that [job] and go?’ I said, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll do even better than this!’” She earned a BA in India, then completed a second bachelor’s degree at MHC.

While her own educational track was rare and radical, Zangmo believes that her country is now ready for sweeping advances that will enhance education for all girls and enlarge the nuns’ role in society. “While respecting and preserving our traditional culture, we cannot expect the nuns to stay where they were centuries ago,” Zangmo says. “The whole country is moving toward modernization and globalization, and we want to include nuns as part of the development agenda so they’re not left out in the twenty-first century. This is especially true since preserving culture, spirituality, and tradition is one of the common threads within Bhutanese society and one of the main pillars of ‘Gross National Happiness.’”

With help from her royal patron, government officials, donors, and her own true grit, Zangmo seems poised to, as Mary Lyon advocated, “go forward, attempt great things, accomplish great things.”

—By Emily Harrison Weir

This article appeared in the spring 2009 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

Learn More by visiting www.bhutannuns.org or read a transcript of our interview with Tashi below.

The text below is an edited version of a transcribed conversation between Alumnae Quarterly editor Emily Weir and Tashi Zangmo in fall2008.

What do you hope will be accomplished by the Bhutan Nuns Foundation?

There are so many little nunneries in every tiny corner of the country. Last summer I realized they don’t have proper teachers, have no curriculum, and the living conditions are very poor, so we are hoping to create a higher learning center which is open to all the nuns in Bhutan.

My vision is to create and teach training for the nuns, teaching leadership training, teacher training, all kinds of things [to benefit the] kids. When the whole country is moving toward development and it’s moving toward modernization and globalization, we cannot expect [the nuns] to stay the way they are. We have to help them move beyond…of course, while respecting and preserving our tradition and culture.

How does the Buddhist religion factor into the program?

I don’t want to change the whole thing, what the nuns are doing. I’m focusing more on the education side, because I don’t have to emphasize strong religious needs; [the nuns] already do that. I come from a very spiritual family, and I am a practicing Buddhist. That’s the main reason that I think I am more inclined to help the nuns.

Why is it so rare for girls to have access to education in Bhutan?

Education is ‘free’ in my country, but then families must buy the uniform, pay school fees, and buy books. All that costs a lot; how many families can afford to do that?

There’s no such rule as “girls cannot go to school,” but by the nature of the country’s geographic location—it is a mountainous country—not every village has a school that is available and conducive to learning. Those are some of the barriers that kept girls away from school, and still it’s happening in the most rural areas.

It’s improved a lot since I went to school, but still we face difficulties because the schools that are located in rural villages are often far away from the [students’] villages—they have to walk at least one hour—so that becomes a difficult thing for the girls.

If a family has five girls, not every girl gets to go to school. There is still some belief that, you know, she’s a girl, so she can stay home and help the mother and that kind of thing. [This traditional view is] still there, even though it’s moved a lot beyond that notion that girls don’t need an education.

What was school like for you in Bhutan?

I came from a very small village in one of the most remote corners of Bhutan, and at that time, no girls ever went to school. From that community, I was actually the first girl-child sent to school.

I think the timing was right [for me to attend school], because in the village my mother saw a couple of local girls were attending school. I can remember only about five girls who were going to that school at that time, out of 200 boys or something.

The only school was a one-day walk from my village. And as a little girl, I started at a boarding school because there was no way I could commute. Since I was the only one who came from faraway village, I started by sharing a room with the boys. They were not organized; the teachers were not ready.

So, a year or two later, more girls started attending school. I was kind of a role model, I think. Now there are so many who go to school, but [most don’t go as far educationally] as I went.

After I finished high school, I started working as a secretary [in the city]. I wanted to study Buddhist philosophy, but then, they didn’t have opportunities for young women like me. Unless you become a nun, there is no opportunity to really study. And I went to India for [further education].

When I was leaving the secretary job [to attend college], I was the only daughter in my family working in the government; it’s a big deal. My family was in shock, [saying] ‘why would you leave that job and go away?’ And I said, ‘don’t worry, I’ll do better than this.’ I finished there and I got my BA degree in Buddhist philosophy. And [MHC] was my second BA.

At that time I was hardly making enough money to feed myself, but somehow in my mind I felt there is something that I can do down the road. I never dreamt of coming to this part of the world. But somehow there was something telling me that there’s something out there that I can do.

How do the nuns feel about the Bhutan Nuns Foundation?

I met with every senior official, every senior monk, and every nun, and with village women. There was a sense that everybody saw the need [for change].

I was being very careful about not trying to put my own ideas into their heads. The nature of questions that I would ask [the nuns] was, ‘what would you wish to have?’ Every nunnery could use every kind of help. But there are many nunneries that need the very basics…they lack basic minimum comforts—no electricity, no bathrooms … no health and hygiene, nothing.

I would ask, ‘if you were given opportunity to study, what would you want to learn?’ or ‘How would you imagine yourself having a better education?’ They were never faced with these kinds of questions before. Nobody cared to have conversations with them or ask them what their needs are, so it was very hard for them to articulate [answers]. They had to trust me to talk about these kind of things.

The majority of them told me that they would like to have … a very structured curriculum, qualified teachers, and to have Buddhist scholars come and teach. But at the same time they were really desiring nun teachers, so they would be comfortable, have some commonalities, and have a mutual understanding for each other.

How did your time at Mount Holyoke contribute to your vision for the BNF?

I had no clue what Mount Holyoke College was all about when I applied. When I came here, I read Mary Lyon’s book [A Missionary Offering] and thought, gee! Mary Lyon really wanted me to come here. Mount Holyoke spoke to my heart and it really helped me to articulate my visions, which I never used to be able to articulate. After coming here, I was able to move forward with that vision, and now I have nuns who are benefitting the community and especially the community of women and families.

Even when I was at Mount Holyoke, I did a little bit of fundraising for the BNF … I supported them whatever little way I could. I used to do a bit of babysitting [while in college] to earn some money. I saved it, then used it to send them clothing—robes for the nuns. One year I did a fundraising Bhutanese dinner in the Berkshires with my friends. [That money funded a] drinking water supply for the nuns. [My efforts] really grew after I came to Mount Holyoke.

Tattoos: Stories in Ink

I got my first tattoo a month after my twenty-first birthday. I had been imagining it for six months and was ready. Or so I thought.

I got my first tattoo a month after my twenty-first birthday. I had been imagining it for six months and was ready. Or so I thought.

Having had surgery earlier in the month, I didn’t anticipate the pain being much of a problem. As soon as my tattoo artist-friend’s needle touched down, however, I was writhing in agony. I yelled louder than the TV I was supposed to be distracted by and ended up shaking in a cold sweat.

But the meaning of my tattoo wasn’t lost in those moments of concentrated pain. I focused on my tattoo’s story instead of the needle.

Before I could even talk, I would look at Audubon bird guides for hours. When I started talking, I could name most of the birds. My grandfather and I used to play a game in which he’d name the species of a bird and I’d find it in the book. That’s how I decided I wanted a bird tattoo.

I settled on an interpretation of a drawing by John James Audubon himself—Tachycineta thalassina, a violet-green swallow, a tiny songbird native to the West Coast. From my limited nautical knowledge (gleaned mostly from pirate movies), I knew that sailors got tattoos of swallows in hopes of seeing the birds while at sea. (Swallows meant that land was near, and they were that much closer to home.)

My swallow perches on the back of my arm, above my left elbow. I catch sight of it sometimes in the mirror—a small, dark figure with wings spread open wide—and am reminded that home, and my family, are always nearer than I think.

A lot of MHC women have stories like mine behind their ink. Traditions, reminders, and wishes are permanently recorded on their bodies, turning each inch of tattooed skin into a story and each body into a vehicle for a subversive form of visual storytelling.

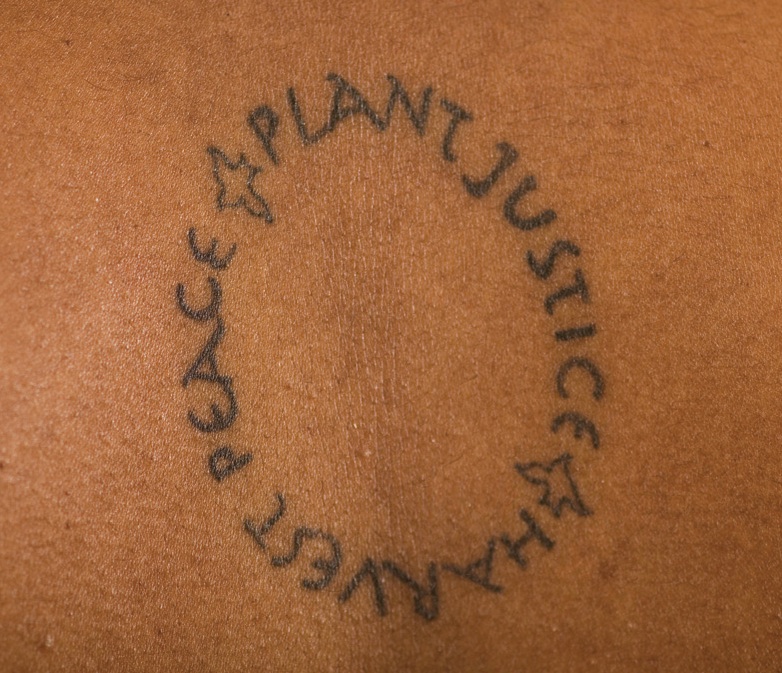

Amika Gair-MacMichael ’09 (above) decided to get a tattoo of the phrase Plant Justice, Harvest Peace “because I couldn’t stop drawing it. I would cover my notebooks with it,” she says. Gair-MacMichael chose this phrase because of her personal involvement in racial and same-sex rights campaigns. “I truly believe in its message and I would like there to be more social equality in the world.”

“Getting a tattoo is not something I thought I ever would do, but I decided to get one during my second year of law school,” says Carrie Ruzicka ’99 (above). “As any former or current law student can attest, law school is not a fun process. But I was not prepared to be so completely underwhelmed by the lack of vision and community that I experienced in law school.

“Without having Mount Holyoke behind me, I am not sure I would have had the confidence and the self-awareness necessary to make it through successfully and on my own terms. That is how I came to get my laurel chain tattoo, an extra reminder of who I am, where I came from, and where I am going. I currently only have one patch on my lower back, but I sized the tattoo so it can grow. Maybe one day my tattoo will drape over my shoulder like the actual chain I carried during the laurel parade.”

After losing one of her ovaries last year, Ryan Dorsey ’10 (above) had her roommate Caroline Heinbuch ’10 design a symbolic substitute ovary and fallopian tube.

After the surgery, Dorsey was left with only one functioning ovary and the possibility that she might not be able to have children. “I began to wonder, ‘What does it mean to be a woman?’” Dorsey said.

“In the end, I realized that being a woman has little to do with the parts that make up your body, or your ability to conceive and carry children. It is a way of looking at the world, a method of problem solving, and [is] so much a part of who I am that it can never be taken away.”

Her tattooed “ovary” is a symbol of the difficult year she endured and the answers she found. “Every time I see it, I am reminded that I am a woman, and by that token, I am beautiful. I find great joy and comfort in that now.”

Twins Lauren (above, right) and Terry Orr ’10 (above, left) decided, along with their older sister Caitlin Orr ’08, to get the same tattoo.

“We thought we would design our own,” Lauren said, “but soon we all fell in love with the idea of getting an interpretation of Gustav Klimt’s painting The Tree of Life.”

Caroline Heinbuch ’10 (above)had a self-designed symbol tattooed on her forearm this past spring. It incorporates her nickname, Caro, with male and female symbols. “I wanted a tattoo mixing the male and female symbols as a representation of the fluidity of sexuality and gender,” she explained.

Meredith Spencer-Blaetz ’11 (above) knew her first tattoo would have something to do with the moon. “As a child, I would search the sky for the moon,” she said. “My mom tells me [that] I used to point at it from my car seat and say ‘Moon!’ Even today, I find that I have a weird [attraction] to it.”

Spencer-Blaetz also has a star on her wrist, in honor of her graduation from high school. “Tattoos are addicting … but I wanted to keep it in check. So I decided that every time something major happens in my life, I would get a star somewhere. Who knows what this life will bring me?”

Bridgette Whitcomb ’09 (above) has Celtic, Hopi, and Lakota symbols tattooed on her lower back. “They are all symbols of family, fertility, or home,” she said. “I had these tattoos done to never forget to go back to the reservation. They remind me that I must go back to Pine Ridge.” Whitcomb spent six summers living on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, visiting friends and family.

She said the Lakota turtle holds the most importance for her. “It is my compass,” she said. “I was worried that I would get disillusioned with the East Coast and forget to go back to the ‘rez.’ I put this on my body so that I would always remember what is important in life and remind me to return home.”

She’s applying for an urban education fellowship, and plans to teach on the Pine Ridge reservation. “I do not want to be a teacher for the rest of my life, but that is the way I see that I can help now,” she explained. “I want to improve the conditions in which people are forced to live.”

Piano player Martha Streng ’12 describes what inspired her wrist tattoo (above): “I knew I wanted a tattoo that had something to do with music, because music is the biggest part of my life.” Her friend designed a heart formed by a bass clef and an upside-down treble clef. “I really loved it,” Streng said, “because it wasn’t a perfect bass clef and treble clef; they were a little more rough and block-like. I hate perfect clefs. I would never want one as a tattoo.”

As far as placement of her ink, Streng said, “Since I have really small hands, I’ve faced a lot of difficulty playing certain pieces.” Putting the tattoo on her wrist was “my way of saying, ‘Yeah, I have little hands. I’m owning it.’”

“Japanese culture is extremely interesting and intriguing to me,” says Amanda ’10 (above; last name withheld by request). Five kanji symbols are tattooed above her hip, representing youth, dream, strength, loyalty, and wind. “The five symbols represent me,” she said.

Margot Wade ’09 (above) had two Spanish phrases tattooed on her ribcage when she turned eighteen, part of coming to terms with her father’s death. Translated, the text reads, “Because we are also what we have lost,” and “Detached from the vaults of Heaven and falls to the earth.” “I got my tattoo in Spanish to remind me not everything is lost in translation, that not everything is lost in the darkness,” she said.

Lynn Tylec ’11 has two roses tattooed on top of her foot, along with the date of her grandmother’s passing.

“One rose is purple, because purple is the color that symbolizes pancreatic cancer,” Tylec said. “The other rose is yellow. My grandmother struggled with weight for years, and she was in a weight-loss group called Take Off Pounds Sensibly. The yellow rose was rewarded to someone who reached their ultimate weight loss goal, which my grandmother did shortly before passing away.”

Caity Bryant ’11 (above)has a sketch of an apple tattooed on her wrist “because I want to be a teacher,” she said.

Kylie McCormick ’08 chose to get tattoos (above) of one of her favorite subjects: dragons. The red “wyvern familiar” is on the back of her arm and shoulder. “I wanted a tattoo to represent the one kind of dragon that could actually be in existence today, which is a wyvern—two legged, two winged, no arms,” McCormick said.

The second dragon is a purple “Ouroboros” intertwined with a yin/yang symbol. “The Ouroboros is an alchemical symbol of destruction, chaos, peace, and transformation. The yin/yang is an Eastern symbol of balance,” she said. “I think they go quite well together.”

Abby Wall ’12 (above) had Kurt Vonnegut’s famous saying, “So it goes…” tattooed above her hip in honor of her uncle’s passing.

—By Hannah Clay Wareham ’09

—Photos by and Paul Schnaittacher and Hannah Clay Wareham ’09

This article appeared in the spring 2009 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

How the V-8s Changed the Face of Campus Music and A Cappella Nationwide

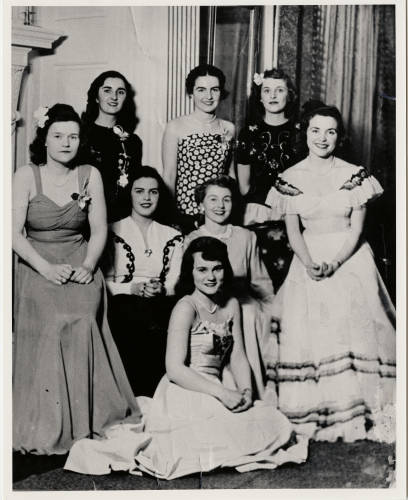

In October of 1942, a group of eight songstresses debuted their skills at Junior Show. As the accompaniment to a student dance number called “My Pajama Ballet,” the singers were off stage, hidden from the audience. By the time their performance was over, however, the crowd had made it clear by demanding encore after encore that the women had created something spectacular.

In October of 1942, a group of eight songstresses debuted their skills at Junior Show. As the accompaniment to a student dance number called “My Pajama Ballet,” the singers were off stage, hidden from the audience. By the time their performance was over, however, the crowd had made it clear by demanding encore after encore that the women had created something spectacular.

To this day, Mount Holyoke’s V-8s is the longest-running female a cappella group in the nation, a well-known fact among Mount Holyoke students. Their legacy extends far beyond campus, however, as the original V8s found fame in New York City by entertaining World War II servicemen at one of the most popular clubs of the 1940s.

The original group can be credited with a turning of the tides on the Mount Holyoke campus. A 1944 article in the Mount Holyoke News described the original performance of the V-8s as “the only evidence, so far as we know, of a former [Junior] Show success continuing as a new college tradition.” In a 2002 letter to the current V-8s, founder Abigail Halsey Van Allen ’44 wrote, “[the group] was conceived as an opportunity to have fun!”

While opposition the original V-8s faced was very slight, it did exist. “Often the music director of the Glee Club and choirs of the time … looked in on us, but did not seem too happy with what we were doing,” Joan Morris McNally ’44 remembered of rehearsals. The selection of modern songs for performance created some waves within the music community, but the V-8s had found something that stuck.

The origin of the group’s name is about as telling of the times as the hairstyles and dresses the women boast in faded photographs. The “V” stood for “Victory,” Winston Churchill’s rallying call of the World War II era. The 8, of course, stands for the eight original members. “Churchill’s raised index and middle fingers of his right hand forming a V for Victory was very pervasive,” Van Allen wrote. “Victory became the spirit of the times.”

The fame of the V-8s began to spread off-campus soon after their debut in Wilbur, Mount Holyoke’s then-student center. They performed at the Westover air force base, parties held for textile-mill workers, and meetings of the Junior League. The V8s were also the first amateur group invited to perform at the Stage Door Canteen in New York City, the most famous entertainment venue for servicemen and the subject of a feature-length Hollywood film (Stage Door Canteen) that debuted the year before the V-8s made their appearance.

The women were largely unimpressed by the Canteen at first glance, according to a scrapbook put together about the original V-8s. Described as reminiscent of someone’s basement, it was not at all what they had been expecting, considering the Canteen’s publicity and fame. The noisy, smoky room in which they performed was so small that some of the servicemen in the audience were actually sitting on the stage with them. The V-8s delivered a rousing performance of popular songs like “The Farmer and the Maiden” and “The Hawaiian War Chant.” Despite the lack of a microphone for half of the performance, Van Allen described the concert as “the zenith and swan song of our original group.”

While a recording was created by the original V-8s, none of the copies exist today. All that is left are a few boxes of yellowed letters and song lists in the college Archives, the memories of the original V-8s, and, of course, the women today who bear the group’s name and legacy. While today’s V-8s have expanded to a group of fifteen, they still feature 1940s classics by Etta James and the Andrews Sisters in their repertoire, reminiscent of the women who have come before them.

—By Hannah Clay Wareham ’09

Reflections on the V-8s Fiftieth Anniversary/Reunion

A poem by “The Originals”, class of ’44 (read by Joan Morris McNally ’44)

We’d like to sing, we really would—

We understand we were quite good.

But after all those fifty years,

Togetherness is gone, me fears!

Instead of blending, all as one,

With harmonies so sweet they stun

(The way we did in ‘forty-three),

We now strike chords sometimes off key.

Yet, anyway, we celebrate

The birth of our fantastic eight:

We sang by ear, and every note—

And lyrics, too— We learned by rote;

We sang at schools, at Westover’s war,

At dances, frats, and famed “Stage Door”.

But best of all, it didn’t end:

“Originals”, we set the trend

You sounded down through fifty years

And brought much joy to countless ears.

So, of ourselves we’ll not just boast—

No! No! We’d like to make a toast:

To all you friends with V-8 style

(And groups to follow in awhile);

To such sophisticated blending,

So full of flavor in the rendering;

To repertoires that change and grow;

Unique arrangements, hot and slow;

To presentations fresh and clever;

To V-8s—may they sing forever!