Journey into Africa

Alumnae confront the challenges with thoughtfulness, humanity, and success

Like so many others in America, Jennifer Kyker ’02 had seen the commercials imploring viewers to send money to help people starving in Africa. They were heartbreaking and compelling, and they’d raised millions of dollars for the cause.

But for Kyker, who first visited Zimbabwe through a high school exchange program when she was fifteen, these organizations’ goals were also painfully narrow. There were plenty of aid groups focused on young children, but by the time those kids had reached adolescence, the programming and funding they needed to thrive had mostly dried up. “Older kids aren’t as appealing—they don’t have those round faces and smiles,” she says. “But that’s when they’re at the highest risk for dropping out of school and contracting HIV. The need is the greatest then.”

It’s part of the reason she started Tariro, an organization that helps provide education and supplies to teen girls who have lost at least one parent to illness or poverty. In the world of international aid, Kyker knows her small organization can help just a tiny segment of the population, but for the sixty or so students that Tariro helps over the course of their adolescence, she knows it will transform their lives. There’s no question that the need is great. Half of the people in sub-Saharan Africa live below the poverty line of $1.25 a day, and literacy rates are lower, collectively, than on any other continent. And more than 22 million people have HIV/AIDS—nearly 70 percent of the worldwide total.

The problems are vast and entrenched. But where some see only hopelessness, many Mount Holyoke alumnae see possibility. It is a philosophy that is practiced in the lives of many alumnae and at the highest levels of the College: President Lynn Pasquerella ’80 makes yearly trips to Kenya’s West Lake District to help a local nonprofit improve the area’s water quality and agricultural practices. (Read the previous Quarterly article about her work.) Mount Holyoke alumnae have devoted weeks, months, and even years of their lives to make a positive difference in the lives of Africans. One person, one school, and one neighborhood at a time, they are changing others’ lives—and their own.

Emmy Murindangamo teaches Heather Baukney Hansen ’94 how to make sadza, a cooked cornmeal dish that’s a staple food in Zimbabwe.

Start With What You Know

The size and scope of the problems in Africa can seem paralyzing, but alumnae have found success by following a simple formula: starting with what they know best.

Perhaps no one knows that better than Zimbabwe native Mufaro Kanyangarara ’07, whose mother died from complications of HIV. When she learned about a $10,000 Davis Foundation grant as a student, she planned a project with Getrude Chimhungwe ’08 to benefit an organization that works with Zimbabwean children orphaned as a result of HIV. Kanyangarara and Chimhungwe won the grant, and with additional funding, they built a chicken farm that the organization maintains to fund specific needs of the orphans, including healthcare. Since its establishment in 2007, the farm has doubled in size (from 500 to about 1,000 chickens) and provides a steady stream of income used to prevent and treat common diseases.

That approach—setting up programs that ultimately can be run without foreign assistance—remains critical to Kanyangarara’s philosophy. She is currently at Johns Hopkins getting a doctorate in international health, but says she plans to return to Zimbabwe, where she can combine her deep knowledge of the culture with the skills she gained through education. “There are a lot of international organizations who come in and try to learn the local setting and implement programs,” she says. “But international organizations should also equip locals with the skills to manage their own programs.”

Fadzi Muzhandu ’05 (right) with Tariro student Tatenda Chizanga, who is now working toward her degree at the University of Zimbabwe.

Kyker’s Tariro has also benefited by working with those who know the culture best. While Kyker can manage fundraising and many administrative details from her home in Rochester, New York, she relies heavily on the organization’s program coordinator and manager, Fadzi Muzhandu ’05. A native of Zimbabwe, Muzhandu works with local schools, parents, and child protection committees as part of her duties. Because of her deep knowledge of the cultural norms and expectations—such as the country’s slower pace or its skepticism about foreign intervention—she can often navigate the cultural terrain more successfully than outsiders.

While the young women who get help from Tariro face an uphill battle, many of the girls have finished their high-school education, and several have gone on to universities. “Tariro is a safe space,” says Muzhandu. “Here, girls have a voice and are allowed to dream.”

Making a Shift

Many of those going to Africa for the first time have strong opinions about specific ways they want to help. But often, as they spend more time there, they adjust their goals.

Such was the case for Liz Berges ’94 and Arden O’Donnell ’97, who spent a year in Zimbabwe in 2002 and 2003. Although they had raised money to build a library before arriving, their time in the country brought more critical problems to light. The well-funded Catholic Relief Services, for example, paid school fees for many children. It was a significant expense and lifted a real burden, but by paying only the school fees and not ancillary expenses, the organization missed a critical piece of the puzzle, says Berges. “In Zimbabwe, public schools require uniforms and school shoes. If you don’t have them, you aren’t allowed in.” Berges wrote about some of these challenges in weekly emails to friends and family at home, and her stories were so compelling that soon people were clamoring to get on the email list. Before long, more than 300 people were receiving her messages, and many of them were sending checks to help out.

Liz Berges ’94 (right) with Lorraine, one of many students helped with school expenses by Coalition for Courage, which Berges cofounded with Arden O’Donnell ’97.

Ultimately, Berges and O’Donnell started their own nonprofit, Coalition for Courage. The funding they receive (more than $100,000 in 2011 alone) pays for everything from food and uniforms to notebooks and pencils.

Their work is making a difference: thanks to their help, fifteen of the students they’ve sponsored have gotten some sort of higher education; thirteen are employed, which is no small feat in a country where unemployment hovers around 95 percent.

While Berges admits that they can’t have the broad reach of larger organizations, the impact they’re making is real. “I think if we weren’t telling these stories, [our donors] wouldn’t be giving to orphans and vulnerable children in southern Africa,” she says. “We can be stewards and make it happen.”

Indeed, their work has inspired several other Mount Holyoke alumnae, including Heather Baukney Hansen ’94 and Bridget McBride ’94, to spend short stints in the country and use their skills to make small but measurable differences. (To read Hansen’s essay, see web extras link at right.) McBride, for example, had received Berges’s emails for years, and decided, almost on a whim, to go with her for a two-week trip to Zimbabwe in 2010. McBride is a nurse practitioner and expected that she would use those skills during her trip. But then she got her packing list, which included pleas from residents to bring sanitary pads. She thought it was a strange request, but then learned that the supplies were expensive for women and teens who had poverty-level budgets.

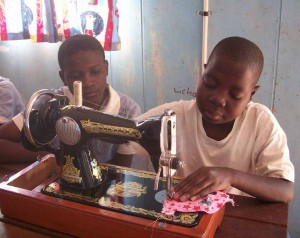

The help she could provide became immediately apparent: “I wasn’t an expert seamstress, but I knew I could teach them to make their own reusable cloth sanitary napkins,” she says.

Jennifer Kyker ’02 practices a traditional Zimbabwean dance with Tariro students, led by teacher Daniel Inasiyo.

What started as a small project to teach ten girls basic sewing skills and create a practical product quickly expanded to eighty as eager women heard about the idea and wanted to get in on the details. “It took on a life of its own,” she says. “People were talking about it in their church groups, sharing knowledge.”

Gail LaBroad LaRocca ’74 also found success when she shifted her thinking. She had visited Tanzania several times through various organizations starting in 1994, and had happily contributed to efforts related to school expenses and food, among others. But the more often she visited, the more she realized that she wanted to focus her efforts on a single thing: clean water, which spurred her decision to start LifeWaterAfrica.org.

Through connections, LaRocca found a Tanzanian craftsman who created biosand water filters, which can provide clean water for thirty people. Each costs just $150 and, with regular maintenance, will last for years. LaRocca has raised enough money for 100 filters; dozens have already been built and installed. “I might not make a big difference,” she says. “But I can make a small one.” In 2010, LaRocca was named one of 100 “unsung heroines” by the Massachusetts Commission on the Status of Women. Still, she says her work is only beginning. “When I reach 1,000 [filters],” she says, “I’ll be shouting from the rooftops.”

For decades, Mount Holyoke alumnae have used time, money, and influence to improve the lives and circumstances of thousands of people. But McBride says that perhaps the most surprising transformation that occurred was her own. “My experience confirmed what I’ve known intellectually but often chosen to avoid emotionally. People all over the world are suffering and desperate through no fault of their own. My world view has been pried open.”

Rows of makeshift tents at Saloum Port on the Libya-Egypt border house refugees from Somalia hoping to start life anew in another country.

Nayana Bose ’90: Rising to the Challenge

As revolutions roiled the Arab world last year, Nayana Bose ’90 spent three months in Egypt helping those who were fleeing for their lives.

An external relations officer at the United Nation’s Refugee Agency (UNHCR), Bose spends most of her time in New Delhi, India. But when the uprisings in last year’s Arab Spring took hold—swift, powerful, and chaotic—she saw an opportunity to step in and assist at a critical time in history. “It took people by surprise,” she says. “We needed more help.”

Emergency teams from aid organizations were overwhelmed by the need, and when her agency requested volunteers for a mission to Saloum, the official entry point between Libya and Egypt, she applied without hesitation. In March 2011, she traveled to Saloum for a three-month mission.

While thousands of Libyans and Egyptians passed through the port each day with relative ease, others had a more challenging experience. Migrants and refugees from countries including Chad, Niger, Pakistan, Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea, and Ethiopia often got stranded for days or weeks as their documents were processed. As thousands of people fled Libya during the revolution, the numbers of those stranded swelled from hundreds to thousands.

Much of UNHCR’s work was basic and critical, such as assessing asylum claims and distributing plastic sheets so that people could make tents to protect themselves from the ferocious desert storms. The organization also offered blankets, sleeping mats, shoes, and clothes.

“The stories she heard were often heartbreaking—migrants who left their life savings in Libya and teenagers who left their families to avoid military service, only to worry that they would never see their loved ones again.”

As a reporting officer, Bose helped keep her organization—and the world—informed about what was happening. Every day, she spent hours talking with refugees and migrants about why they were fleeing and their concerns about their current situation. She did interviews with international media, wrote stories and Facebook updates for UNHCR, and sent reports back to agency headquarters. “A typical day started at 9 a.m. and ended at 11 p.m., and we worked seven days a week, with five days off after two months,” she says. “It was a punishing pace, but that’s what an emergency mission is about.”

The stories she heard were often heartbreaking—migrants who left their life savings in Libya and teenagers who left their families to avoid military service, only to worry that they would never see their loved ones again. One young man told her he’d lost his best friend in the war, then pressed a poem into her hand that he had written about his experience. “It sounds like a bad Hollywood film,” she says. “But it was their reality.”

But there were also small moments of grace. She grew fond of the people she saw daily, from shopkeepers to bakers. She even came to an uneasy peace with the restrictive Bedouin traditions. And each day, she took forty-five minutes to walk along the corniche, the road by the sea. “Saloum was right on the dazzling blue Mediterranean, and that walk was the highlight of my day,” she says. “It kept me going.”

By June 2011, UNHCR—along with the International Organization for Migration—had helped 36,000 people to cross the border and get home. But for Bose, it is the people, not the numbers, that remain etched in her memory. “I have taken their tales with me back to New Delhi,” she says. “It was a soul-stirring experience.”

—By Erin Peterson

This article appeared in the spring 2012 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

April 20, 2012