Making the Grade: What’s Right with U.S. Public Education

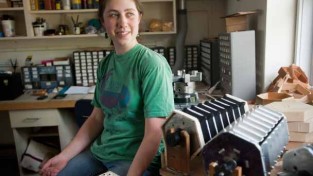

Day in the Life of a Teacher: Science teacher Sherri Svedine-Gaskalka ’92 let a Quarterly photographer shadow her for a day in early September. Her work teaching AP biology and chemistry in inner-city Springfield, Massachusetts’s Central High School demonstrates what high standards, personal attention, and hard work can help students achieve. She arrives at 7 am, teaches six classes and labs a day, eats lunch at her desk, and participates in meetings with colleagues and/or parents after the official school day ends. Then the grading—and preparation for future classes—begins.

Amid the drumbeat of bad news about America’s educational system, Mount Holyoke alumnae are using their skills to make improvements—one student, one classroom, and one school at a time.

When Meredith Louria ’77, an English teacher at Santa Monica High School in California, opened the newspaper early one June morning and saw the advertisement for the movie Bad Teacher, she couldn’t help but cringe. The summer popcorn flick features Cameron Diaz as a raunchy, self-absorbed middle-school teacher who announces that she chose the profession for “short hours, summers off, and no accountability.”

The film is a comedy, but Louria knows that too many people assume that Diaz represents many teachers. “I’m sure there are people like that,” Louria says. “But [the stereotype] makes the movie—it’s not the quiet, effective work that most of us do every day for thirty or forty years.”

Public educators—and the public education system—have been taking a beating in recent years. In many cases, it’s for good reason: statistics suggest that American students’ science and math proficiency is among the worst in developed countries; dropout rates for minority students hover near 50 percent; and the movie Waiting for Superman, a devastating portrait of education in America, sparked a national discussion about how the educational system must be fixed.

There’s no question that there are very real problems within public education. But even as the TV pundits and newspaper editorial writers skewer teachers and schools, the amazing work of many educators bubbles just beneath the surface. Mount Holyoke alumnae are working at every level to make a difference in the lives of individual students, in classes, and in schools. Their work may not make front-page news, but it is effective and inspiring. And their stories provide some of the optimism needed to support real and lasting change.

Thinking Big

Laura Rogers ’72 is codirector of the school psychology program in the department of education at Tufts University. Two decades ago, she was working on the school committee in her town of Harvard, Massachusetts, when a friend and advocate for educational reform, Ted Sizer, urged her to spend a day shadowing a student in a well-respected local high school. She admits she was disappointed. “I never heard a question asked by a teacher or student that couldn’t be answered in one sentence,” she says. “If your aspiration is that students should learn to think critically and weigh evidence, then you should see them practicing that in the classroom.”

It was that experience, in part, that inspired Rogers to become a founding trustee at the F. W. Parker Charter Essential School in Devens, Massachusetts, which opened in 1995. The school followed “The Ten Common Principles of the Coalition of Essential Schools,” which included small student loads for teachers and a focus on helping students use their minds well.

The principles are more than talking points. Advisory periods, in which groups of a dozen students and one teacher meet, bookend each day. Students develop customized learning plans each year and take part in community-service activities. “We wanted a school that would be more responsive to the range of students and their needs as young people,” Rogers says.

Results suggest that the approach is working: students are achieving state-required levels of proficiency and don’t get lost in the shuffle. According to 2010 statistics, about 80 percent of all Parker attendees have gone on to graduate from a four-year college.

Building Better Teachers

As charter schools like Parker seek to redefine the educational experience of students, Karen Bang-Jensen Zumwalt ’65 and her colleagues at Columbia University Teachers College in New York City are finding ways to reimagine teacher education.

For decades, there was essentially one path to teaching: students went to college (and sometimes graduate school) to get certified to teach. It remains the dominant model, but new approaches are starting to take hold.

Teach for America and Teaching Fellows programs, for example, work with recent college graduates and career-changers who haven’t followed traditional teacher-education routes. The programs fast-track members’ preparation, and within a matter of months or even weeks, they can become the teacher of record in classrooms of low-income communities. While such programs can attract a diverse group of potential teachers and fill important positions that might otherwise go empty, this approach has its drawbacks, says Zumwalt. “Because these people are learning to teach while they’re the teacher of record in the classroom, they haven’t necessarily had enough preparation,” she says. “They’re experimenting on very vulnerable students who have great needs—students who present challenges even for very experienced teachers.”

To get the best of both worlds, Columbia recently created the Teaching Residents at Teachers College program, which works much like a medical residency. Students come into the program and get a stipend, a significant scholarship for Columbia’s master’s degree program, and work in a classroom with an experienced teacher for a full year. Zumwalt thinks the hybrid approach might make a real difference, particularly since similar programs in other cities, including Denver, Chicago, and Boston, have

been promising. It’s also helping schools fill positions where there have traditionally been significant shortages,such as secondary special education and Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL).

While the program is small—Zumwalt expects twenty-five to thirty people to go through the program annually—it is a step in the right direction. “There are lots of good little projects like this going on,” she says. “I hope they will blossom, and become a new model we can use.”

Partnerships that Work

Just a few miles south of Zumwalt’s office at Columbia are the offices of the Fund for Public Schools. Tara Paone ’81, their chief financial officer, has overseen some $300 million in donations received from philanthropists since 2003.

Paone says the public-private partnership is uniquely positioned to offer support to schools that public funding can’t. “What we do is more like research and development,” she says. “The public sector still takes on the lion’s share of what needs to be funded, but private dollars can support innovation, research, and development around ideas that still haven’t been completely fleshed out.”

One wildly successful program that developed with the fund’s support is the School of One, a digital math program that combines teacher-led instruction, one-on-one learning, independent work, and virtual tutoring. Time magazine, which named it one of the fifty best inventions of 2009, called it “learning for the Xbox generation.”

The fund’s current programs are diverse, but “innovation is the common theme,” says Paone. “We’re always looking for ways to support students, teachers, principals, and schools.”

Other major cities with notable philanthropic communities are taking note; recently, the Los Angeles public school system has been looking at developing a similar program.

Best Practices

Grand plans for education are important, but so are the countless daily interactions between teachers and students. These moments—where the chalk meets the blackboard—are what affect students perhaps most directly and deeply. More than 1,400 Mount Holyoke alumnae are currently teaching. Their stories illustrate the power of a single teacher to change lives.

Perhaps one of the most stunning successes is powerhouse Nancy Ahlberg Mellor ’59, who over the past quarter century has been honing a remarkable program now known as CHA House. The program, which she started as a teacher at Coalinga Middle School in California, pulled intelligent—but not necessarily high-achieving—Spanish speaking students into her math classes. There, she pushed them, cajoled them, and dared them to dream bigger.

Along the way, she built a partnership with the University of California at Berkeley. She helped build a successful summer program at the university that allowed these high-potential students to develop their skills and see the possibilities that might exist outside of their tiny farm towns. “I realized that kids can dream about what they want to do, but they can’t do it unless they have the words to dream in,” Mellor says. As a result, students who might have gone back to work on farms have instead pushed

themselves to attend to community colleges, state colleges, and world-class universities. Of the 400 or so students who have gone through her intense program, Mellor estimates that 160 have graduated from college and another seventy-five are currently in college.

Meredith Louria, the Santa Monica English teacher, has taken full advantage of opportunities for fellowships and grants. For example, after a US State Department fellowship in 2004, Louria created a partnership with Nadezhda Strueva, a teacher in Russia. In 2007 she received a grant from Facing History and Ourselves to create a curriculum with Strueva. The two have retooled their teaching to take advantage of that connection. During one unit, her ninth-grade students read a dystopian novel and do a project based on the reading. One option is We, by Yevgeny Zamyatin. “The project for students who read that novel is to ‘talk’ to the students in Russia about the book,” Louria says. Because of the eleven-hour time difference, students write messages to each other online. Technology enables this communication, but it’s great teaching that makes these connections valuable. “Students get excited not that they’re doing projects on the Web; they’re totally excited that they get to talk to their counterparts from another country.”

Beyond the ambitious programs and whiz-bang technology, there is an almost endless number of teachers making a difference in students’ lives through their day-to-day actions. Alexa Encarnacion ’02, a history teacher at the Manhattan Center for Science and Mathematics in New York, says it’s easy, from her vantage point, to see the herculean efforts that most teachers put into their job. Despite constantly changing policies for testing and achievement, despite draconian rules that mean she can’t hug a student for fear of a lawsuit, and despite the constantly increasing class sizes, she says the vast majority of teachers are doing good—if not remarkable—work.

“My [teacher] friend was thirty-eight weeks pregnant, but she kept going to school so she could be there when her kids graduated,” Encarnacion says. “Teachers stay after school working on essays with kids, even if they don’t get paid. I’ve had friends write fifty or sixty college recommendations a year, without any expectation of getting paid.” She says she sees teachers fighting to get the troubled but promising students into AP classes, in which a single spark can ignite a passion that fuels a career. Encarnacion created a race, class, and gender course because students were clamoring to talk and think about issues that weren’t discussed in the available coursework.

Emilie Ronallo ’05, a second-grade teacher at SPARK Academy in Newark, New Jersey, says teachers in elementary schools are making similar efforts. She puts in even longer hours than her students, who are at school for nine hours each weekday, plus Saturday sessions for field trips and supplementary classes for families. Ronallo often visits her students’ homes, and says that her students benefit from all the time and attention teachers spend on them. Indeed, she adds, students often achieve more than they

ever thought possible, such as reading and writing in second languages as early as kindergarten. It doesn’t surprise her. “When you have high expectations of students, they will rise to meet them,” Ronallo says.

Looking Forward

It’s easy to find flaws in the public-education system, but those who work within it also know that there is a great deal of positive change happening. Instead of spending so much time focusing on the failures, many would like to focus on what’s going well—and to scale up these ideas and programs.

For Karen Zumwalt, governments and businesses can do many things, but it’s the people who take jobs in the field who will make the difference. “I meet fantastic people every day who are passionate about teaching,” she says. “And that’s what gives me hope.”

—By Erin Peterson

This article appeared in the fall 2011 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

March 30, 2012