Interview with “A Discovery of Witches” author Deborah Harkness ’86

Of Witches, Women, and MHC: An Interview with A Discovery of Witches Author Deborah Harkness

Of Witches, Women, and MHC: An Interview with A Discovery of Witches Author Deborah Harkness

In addition to writing bestselling fiction, Deborah Harkness ’86 teaches in the University of Southern California at Los Angeles Department of History, specializing in the history of science. She is the author of two nonfiction books in addition to A Discovery of Witches, the first volume in a planned “All Souls” trilogy. Below is an edited transcript of an interview with her in April 2011.

—By Emily Harrison Weir

Q: You’re back home in California now. Is the tour launching A Discovery of Witches over?

It’s finished here in the US, but it keeps rolling out in other places—I’m about to go to Europe for the French publication—so it’ll be a while before I can call it over. And the minute I do, the paperback will come out here and it’ll start all over again. And then the second book will come out…

Q: You’ve received fellowships and awards for your scholarly work, but I imagine it’s another order of magnitude to have fans in the pop-culture sense.

Nobody expects anything like this to happen to them. My outer limit of [my expectation of] success was that the book would be published. And the book has so hugely exceeded that in some ways that I haven’t completely absorbed it all.

Q: What aspects of Witches, if any, can trace their heritage to your MHC experiences?

I have a personal commitment to the liberal arts that I got from MHC. So even though [the book’s heroine] Diana goes to Bates—that was my 2nd choice—the whole book is a kind of love letter and a poem to what a liberal arts college represents both for Diana and for Matthew. In the way it situates you in a world of ideas and texts—that I experienced for the very first time at MHC and it is still very precious to me.

That can be undervalued in our world of professionalization and specialization. People say only a historian could have written this book, and I say, no only a liberal arts college graduate could have written it because of the way it pulls from literature, history, science…from the kind of broadly conceived education that MHC and other liberal-arts colleges represent.

Q: You have very strong female characters throughout the book. Is that related to your MHC experience?

What I really wanted to do in this book was to explore an issue I first became aware of at MHC, the issue of a woman accepting who she is and the power she has. Maybe she’s not a witch, can’t conjure up fire, but women have all kinds of power, yet most of us have very conflicted notions about having that power. There’s both a desire for power and women don’t know if they should want it. And if they have it, women wonder if they can wield it in a way that is humane and strong.

So this is really a book about women accepting the power of who they are. You see that in a lot of the female characters: Ysabeau and Sarah have fully accepted who they are and their place in the world, but Diana, who is on top of her game professionally, is kind of blind to the power that she has. Diana fills her life with all kinds of things to distract her from taking a hard look at herself.

The reason I feel strongly about this issue is because, at MHC, you spend four years in an environment that’s very accepting and nurturing when it comes to realizing your full power. Then a lot of us discover that the world isn’t as hospitable as MHC was. Some of us have to go through the process all over again of going back to what we learned [about power] in college and not giving that up just because we’re now in a world that doesn’t support it.

I teach graduate students and went to graduate school, and in both cases I could spot the women’s college graduates. And I can [do the same] in my own faculty and my graduate seminars. I can be in a meeting with thirty people I’ve never met and I can tell you who went to women’s college, because they don’t necessarily accept a secondary role. They voice their opinions, and they live a life without apology. They’ve accepted their power.

Even very smart, accomplished women can hold back and not fully engage with the world. It’s really important to me that there be women in fiction who show that struggle and come out the other side of it with a knowledge of who they are, something I was fortunate to get at MHC. I know for sure that I would not be a professor, I would not have written this book, if not for MHC.

Q: I’ve read that, before Witches, you hadn’t written any fiction since a tenth-grade short story assignment; is that correct?

Yes. Writing fiction wasn’t a decision, it was a complete accident. I didn’t even tell people, or even really recognize myself, what I was doing until about six weeks into the process. I became fascinated by modern popular culture’s fascination with the occult because I study people in the sixteenth century with a similar fascination.

My students say, “well of course they [sixteenth century people] believe that, but they’re so different from us.” And then you look at what we’re reading [Twilight, Harry Potter, etc]. I kept thinking, a sixteenth-century person would be completely comfortable with these stories of the supernatural and strange.

I became interested in figuring out what it is that draws us to these creatures, and imagining what kind of world we’d have to have if, as my sixteenth-century subjects believed, [supernatural creatures] are really out amongst us.

Q: How did this fascination turn into a novel?

As I tried to imagine what the world would look like if vampires and witches and demons and ghosts and haunted houses and everything else really existed, it quickly became an issue of me imagining that world through specific characters.

I have a character-driven approach to history, I’m very people-centered, so things don’t work for me in the abstract as well as in an embodied form. So I imagined. In history, I can pick a real person and learn about them and their world through their eyes [through research]. But in this case, I needed to make them up to imagine the world. So I started doing that and six weeks later my imaginary people were talking to each other and walking around the city of Oxford, going to their jobs, and I came out of my office and thought, “Oh my god, I think I’m writing a novel!” So it just kind of happened…delightfully so.

Q: I imagined you’d need to retrain your mind consciously from writing scholarly nonfiction to writing imaginative fiction, but it sounds like the transition happened naturally.

It really did. I had been thinking for some time, and have written for the American Historical Association, about what historians can learn by thinking about their scholarly work more in terms of character and plot. People say about my scholarship that the people seem so three dimensional. I try never to forget that these were real people who walked around and had emotions and troubles, and there’s only so far the historical evidence will give me access to that part of them, because in my period the evidence is limited when it comes to reflective writing. So in some ways I’m very bound by the limits of evidence in my scholarship. What I love about fiction is that there’s no boundary. Once I’ve created a character, what I say goes. There’s a definite compatibility [between scholarly writing and fiction].

Q: Can you explain how your character-driven approach to history comes out in your classes?

I get up in front of my students and try to explain a world that really was quite different from their world. Sometimes it can be perplexing for them. But it makes a difference to my students when I say, for example, “Henry VIII was eighteen when he came to the throne. He’s your age. If you were handed a country, what would you do? And they always say the same thing: Party! So I’m like, there you have it.”

In my classroom, I work a lot on developing historical empathy, developing a modern eighteen-to-twenty-one-year-old’s ability to look back at people in the past and not just judge them but to understand them. I think that’s the work of a historian, to understand why a person did what they did at that particular moment in time.

That also rolls over into my fiction, where my characters must have a logic based on what that character would choose, given a limited range of options. That feels very much like historical work to me. But since my characters are imaginary, instead of having to look up the answer, I get to make up the answer.

Q: Did you have any literary models for Witches?

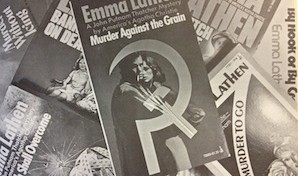

You can trace my book’s antecedents to four books, all from the 1980s, the last period of my life I had time to voraciously consume literature: AS Byatt’s Possession, Anne Rice’s The Witching Hour, Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon, and Dorothy Dunnett’s books [such as the historical fiction series The Lymond Chronicles, and The House of Niccolo.]

My MHC senior thesis adviser Sally Sutherland, after I finished my honors thesis, told me to read [Dunnett’s] series set in the mid-sixteenth century, which has a dashing hero; they are historical romances that are hugely detailed and heavily researched.

The more recent literary works haven’t influenced me. When I think of scholarly mystery, I think not of Dan Brown, but of AS Byatt.

I did read Harry Potter because, when I gave my first lecture in magic and alchemy and talked about Nicholas Flamel [a fourteenth-century alchemist] the students looked bored, because they already knew all about him creating the philosopher’s stone from Harry Potter. So I ran out and got Harry Potter. That made me realize that it’s not just kids who like this kind of thing; adults were stealing their kids’ books to get it.

Q: How have your historian colleagues reacted, and how have you reacted, to your pop-culture fame?

I’m in an uniquely supportive environment: the University of Southern California has a reputation for interdisciplinarity, and for supporting the connections between the academy and the public. My colleagues been wonderfully supportive, and my students are supportive too.

Q: Do readers of Witches greet you differently than those who know your scholarly work?

No one has ever run up to me and said, “I just love what you do with John Dee; can I give you a hug?” [He was the subject of her scholarly book John Dee’s Conversation’s with Angels: Cabala, Alchemy, and the End of Nature.] But people have said that about Diana and Matthew.

My favorite part of my new life as a fiction writer is meeting readers. It feels very much like the classroom, and I’m always fascinated by what intrigues them. I’m especially gratified at the number of people who say either that the book reminds them of all the things they loved about history when they were students, or say, “I never liked history but now I am at the library checking out books on the crusades to understand Matthew better,” or “I’m taking French again because I realize how I love the language.” So it feels like I have a big classroom.

Q: Is there a connection between the female-centered Bishop family and the female-centered world at Mount Holyoke?

There is very much a connection in the sense of what’s absent [for Diana] and what you get hints of with the Bishops. Sarah and Emily are really embedded in a very tight world of women (and some men) that’s supportive that constitutes a kind of large family—things that remind me of my MHC experience [such as] what it’s like to hear nothing but women’s voices at dinner…the happy buzz of intelligent conversation.

Diana has only one friend; she lacks that sense of community of female support that is critical to a woman being able to spread her wings and do what she’s uniquely able to do in the world. That’s one of the things the next book is going to explore. Diana must confront the fact that she keeps herself at a distance from people who might very well be the support that she needs, and she must begin the process of finding those worlds of women of different sorts who will be there for her.

MHC Is there in the absence in [Witches] in the sense that I’m not sure how a woman takes risks without having that kind of gynocentric world of support. I take for granted when I meet with women that they are sisters and can occupy the place in my later life that all the strong, smart, adventurous women I knew in college had. After MHC, you know other women aren’t your enemies or competitors.

Q: With all the publicity and touring, how are you finding time to teach?

I am on leave this semester because I haven’t learned the spell for being two places at one time. But I will be back in the classroom this August. I wrote and edited Witches while teaching full time and directing graduate studies. It’s not necessarily a recommended course of action for an aspiring fiction writer, but I did it, so I’m cautiously optimistic that it will work a second time.

Q: And now the question your readers want most to have answered: when is book two of the “All Souls trilogy” coming out?

We’re hoping to have it out in 2012. When I’m not zipping around talking to readers I’m here chained to my computer writing up the next stage of the adventure. Do you want it now, or do you want it to be good?

• Listen to one of Harkness’s favorite interviews, a five-minute audio talk broadcast on WWNO in New Orleans. (“The Sound of Books” by Fred Kasten)

• Check out Harkness’s Facebook presence.

• Read an excerpt from A Discovery of Witches

July 14, 2011

[…] Read more […]