On Display: Markers of Grief

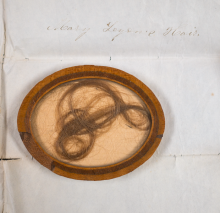

Mary Lyon’s hair jewelry

On the evening of March 5, 1849, Mary Lyon’s close friend Rebecca Fiske sat down to write a letter to her dear friends to inform them about Lyon’s condition; she wrote, “Have you been anxious about Miss Lyon? What should I tell you of her? She is near the end—.” As she scrolled out the last dashes, Fiske was alerted to Lyon’s death. Although likely shaken by the news, she returned to her pen and paper minutes after and wrote, “I was just going to tell you that she was near the gate of heaven. . . . She is already there—at rest in the bosom of her savior, it was about half past eight, her spirit took its flight from earth.”

In the days, months, and years that followed, Lyon’s hair was distributed to friends and students.

Mary Lyon’s earthly remains would be prepared for burial, and although it is not clear when her hair was shorn from her head, we do know that in the days, months, and years that followed, Lyon’s hair was distributed to friends and students. The act of disconnecting hair from the body marked a “rite of passage whereby the hair is transformed into a personal relic and a model of remembrance,” according to Karen Bachman, a professor of design at Fashion Institute of Technology, jewelry designer, and author of a 2013 journal article “Hairy Secrets: Hair as Human Relic in Jewelry.” Mary Lyon’s locks would be transformed into a variety of memorial objects. Some of these objects found their way back through Mount Holyoke’s gates.

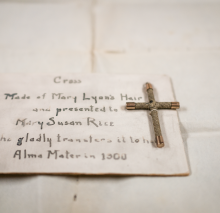

The objects in the College’s collection include three crosses, a bracelet, a ring, one vial of hair, and hair in a wooden frame. These items may seem morbid or even repulsive to some, but when positioned in historical context it is possible to see that hairwork was a means for nineteenth-century American society to mourn the departed. The nineteenth century marked the beginning of the United States’ sentimental era, a time when overt emotional expression was best kept to oneself. Despite this time of emotional restriction, the art of hairwork gained popularity as an acceptable means of “outward expression of [a] person’s inner sentiments,” according to historian Helen Sheumaker’s work Love Entwined: The Curious History of Hairwork in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007).

Hair jewelry became a symbolic language that narrated to the public the wearer’s story of grief and sorrow. Jewelry made out of hair had the power to connect the living and the dead when kept closer to the wearer, who was comforted by the fact that the lock of hair taken from their loved one’s head would be frozen in time, maintaining its natural color and texture for the remainder of her lifetime and beyond. The College’s collection of Mary Lyon’s hair jewelry is housed at Archives and Special Collections, where visitors can see for themselves the intricate artifacts of Mount Holyoke’s influential founder.

—By Brie Lowenstein FP’14

—Photos by James Gehrt

This article appeared in the fall 2014 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

October 15, 2014

Leave a Reply