The Great Divide

In the College’s centennial year, a male president took the helm for the first time.

No fanfare accompanied the departure of Mary Emma Woolley on July 27, 1937. Her staff watched from the President’s House as the large car turned left on College Street and headed north, followed by a small truck piled with suitcases, hat boxes, and crates containing china, curtains, and the books and papers of her presidency. The most visible woman in American higher education sat erect and alone in the rear seat as she bade a silent farewell to Mount Holyoke College.

Although she would live another decade, Miss Woolley, as many students of the time called her, would never return to the campus in South Hadley. The reason was simple enough: Her successor as president, Roswell Gray Ham, was a man.

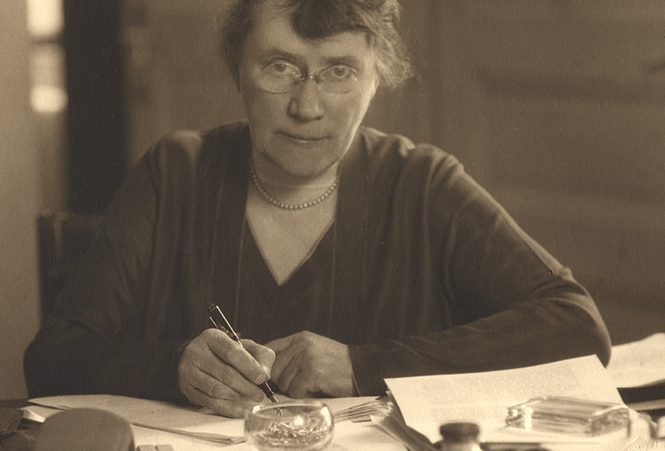

Woolley had transformed a quiet school devoted to training Christian girls into a community of women scholars. She introduced comprehensive entrance examinations and ended the requirement that students perform domestic duties. She made a PhD requisite for faculty status. In shaping a rigorous academic environment, she sought to train women to be leaders at home and abroad. (At United States President Herbert Hoover’s invitation, she served in Geneva as a delegate to the Conference on the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments in 1932, an unprecedented honor for a woman.)

President Woolley at the Conference on Reduction and Limitation of Armaments, held in Geneva, Switzerland, 1932-1933.

Just a few weeks before her 1937 departure, a range of accomplished women had assembled to celebrate the College’s centennial, including Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, class of 1902, the first woman to serve in the US cabinet. By all accounts, the May weekend had been memorable; as Radcliffe president and Smith alumna Ada Comstock concluded, “Never in my experience has an audience been so deeply stirred by a conviction of the importance of giving free and wide opportunities to women.”

Yet, to Woolley’s indignation, a century of unbroken female leadership had ended, as one of the most visible of those opportunities, her very job, now belonged to Ham, an associate professor at Yale and a former Marine Corps captain in the Great War. The announcement of his appointment a year earlier had been a stunning blow to Woolley, College faculty, and many alumnae. The likable Ham, a self-effacing scholar best known for his knowledge of John Dryden’s poetics, could claim little administrative experience. Perkins spoke for many when she disparaged him as a man of “ordinary capacity.”

A Committee’s Decision

The back story begins with the letter of the law. As chartered by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Mount Holyoke College was administered by twenty-five trustees. Twenty were self-elected for ten-year terms, while five alumnae were chosen by other graduates to serve for five years. Charged with the overall governance of the institution, the trustees chose the president of the College, who also served as an ex officio board member.

In the mid-thirties, the majority of Mount Holyoke’s board members were men; in addition to the alumnae representatives just two women served as trustees. The eighteen male members consisted of two ministers, one school headmaster, an attorney, and a majority mix of businessmen, including industrialists, bankers, and financiers.

In the mid-thirties, the majority of Mount Holyoke’s board members were men; in addition to the alumnae representatives just two women served as trustees.

At the time, there was no fixed expectation for the gender of presidents at elite women’s colleges. Among Mount Holyoke’s peers in the Seven Colleges Conference neither Barnard nor Wellesley had ever had a male president; Vassar and Smith had never had female heads. (In a curious inversion of the Mount Holyoke story, Smith’s first woman president would take office in 1975, the school’s centennial year.) Although Bryn Mawr and Radcliffe had been led by men in the past, the office holders circa 1935 were women.After her return from the Geneva conference in 1932, Woolley and the trustees agreed her retirement would coincide with the College’s centennial. In the fall of 1934, a five-member Committee on the Succession to the Presidency was established to identify candidates. The committee assembled a long list, including names suggested by Woolley, the faculty, alumnae, and others. The suggestions were winnowed down to a list of seventy-one, and, late in 1935, four additional trustees were invited to join the committee. The nine-member committee then consisted of five men and four alumnae, with a notable Yale-related constituency, as a third of the committee had strong New Haven connections (Lottie Bishop, class of 1906, was as executive secretary at Yale, Howell Cheney a member of the Yale Corporation, and Edgar Furniss dean of Yale’s graduate school).

However, there was a strong expectation among members of the College’s entire board of eighteen men and seven women that the committee, adhering to tradition, would nominate a female candidate. That proved illusory from the committee’s first meeting. “I am the only one on the committee who believes heartily that if a really suitable woman for the position can be found, she should be preferred to a man,” alumnae trustee Rowena Keigh Keyes, class of 1902, wrote, in January 1935, to fellow trustee and classmate Frances Perkins.

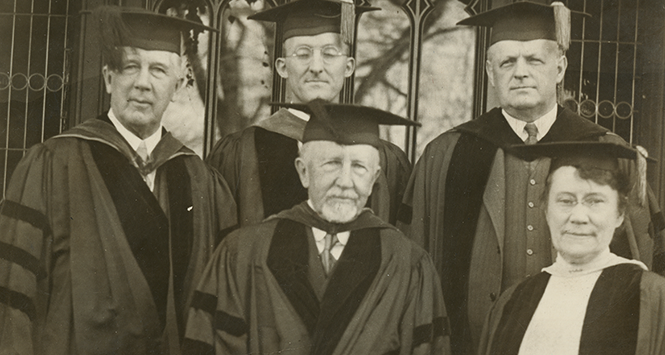

President Woolley and four College trustees, later involved in the selection of Roswell Ham as her successor, 1934.

In 1931 Woolley had confided to a friend her concern at the board’s “masonic character”; her worries proved prescient, as interviews conducted with male candidates went unreported to the larger body of the committee. The names of some of those interviewed (including Ham’s) never appeared on the candidate list. Only many decades later, with the 1999 deposit of a cache of internal board correspondence at the College archives, did the extent of the behind-the-scenes maneuvering become known. These documents are the basis of a detailed and compelling recounting of the events in the recent book A Male President for Mount Holyoke College by Ann Karus Meeropol, a former LITS Scholar-in-Residence at the College (McFarland, 2014).

The events unfolded after board of trustees president Alva Morrison confided in President Woolley, in May 1936, that the board had offered Ham the job. Ham had accepted, and, Woolley was told, his appointment would be ratified at the forthcoming trustees’ meeting.

Woolley rose to express her adamant opposition at the committee’s June meeting. “I can imagine no greater blow to the advancement of women than the announcement that Mount Holyoke celebrates its centennial by departing from the ideal of leadership by women for women, which inspired the founding of the institution and which has been responsible in large measure for its progress.” A prolonged public airing of the dispute followed, during which a range of faculty, alumnae, and outsider voices attempted—and failed—to derail Ham’s inauguration.

A Mixed Legacy

Mary Woolley had been a pioneer, the first woman to enroll at Brown, earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees. After accepting a post at Wellesley, she rose rapidly to full professor, head of the biblical studies department, and gained wider recognition. At age thirty-eight, she accepted the job as Mount Holyoke’s eleventh president.

Everyone agreed her presidency had been a resounding success. In raising the College’s visibility and intellectual caliber, she had gained national recognition not only for Mount Holyoke but also for herself. Smith College president William A. Neilson put a widespread perception into personal terms when he observed, “Mount Holyoke is Miss Woolley.” His admiring remark had a negative connotation: Though hers would be a hard act to follow, some of the trustees appear to have suffered from what might be called Woolley fatigue.

Faculty members in President Woolley’s inauguration procession, May 15, 1901.

The board had wholeheartedly endorsed Woolley’s participation in the Geneva peace talks, but her commitments to numerous organizations had frequently taken her away from the College, including six months spent in Asia on the China Education Commission. She lectured widely, and her three terms as president of the American Association of University Women, she admitted, amounted to a second job. She was also a professed pacifist as well as an outspoken supporter of Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose policies were anathema to most of the conservative businessmen who populated the Mount Holyoke board.

In a more intimate sphere, Woolley’s long-standing relationship with Jeannette Marks was, for some, a source of discontent. A former student of Woolley’s at Wellesley, Marks followed Woolley to Mount Holyoke and became a professor of English literature. Since 1909, the two women had both resided in the newly constructed President’s House. While they maintained separate quarters—and Woolley took pains to maintain a cordial formality with Marks in public—their relationship was widely understood to be a life partnership.

Some on the faculty grumbled that Marks received special treatment, but, more damning, Woolley’s connection to Marks played into what newspapers, opinion-makers, students, and others far from South Hadley had begun to say publicly, that progressive women—Woolley was just one visible example—were out of touch.

Woolley’s generation had aspired to independence. At her arrival in South Hadley in 1901, roughly one American woman in five remained unmarried. It was a time when many College alumnae pursued professional careers and maintained rich friendships with other women, not a few of them as couples; among the faculty on the campuses of women’s colleges, married women were the exception and female couples commonplace. But that was changing. Among newly enfranchised women who came of age in the highly sexualized 1920s, the number who remained unmarried dropped precipitously. By mid-century, the ratio of single-to-married women would fall to one in twenty.

To their critics, women’s colleges had become “feministic” and “over-feminized.” (The Boston Globe used the term “spinster management,” and those who protested Ham’s appointment were dismissed as “a handful of antiquated females.”) The pre-war years saw a decline in separatism—a strategy manifest at the turn of the century in the successful suffrage movement, women’s clubs, settlement houses, and thriving women’s colleges. In feminist historian Estelle Freedman’s succinct estimation, “The old feminist leaders lost their following when a new generation opted for assimilation in the naive hope of becoming men’s equals overnight.” President-designate Ham expressed this narrowing of expectations when he told the Holyoke Transcript-Telegram: “The fact must always be kept in mind that women’s main vocation is marriage.”

Woolley had managed through difficult times, but there was a perception that a male president would bring a sharper business acumen.

In short, Professor Ham was the antithesis of President Woolley. His sudden emergence as the board’s choice after not having been on the short list may actually have been the result of the widower’s remarriage in early 1936. Trustee Henry Kendall, a highly successful businessman and the son of Mount Holyoke’s oldest living graduate at the time, had worried aloud at Mount Holyoke’s “lack of social facilities” and, according to Frances Perkins’ recollections, was among the board members who wanted a “president who had a nice wife who could entertain visiting dignitaries and trustees and would be the charming hostess.” The new Mrs. Ham had impressed the trustee interviewers as a valuable presidential partner. For the businessmen on the College board, the demographic changes were a practical concern; as chairman Morrison saw it, “a majority of our own trustees . . . [will] not send their daughters to Mount Holyoke.” They also worried about money; they wanted not only to attract the daughters of affluence but to ensure sound fiscal management. Woolley had managed through difficult times, but there was a perception that a male president would bring a sharper business acumen.

As Morrison explained bluntly to a new alumnae trustee in the weeks before Ham was named president, the circumstances all added up to one conclusion: Mount Holyoke needed, he wrote, “A strong man at the head.”

A Man at the Helm

Four members of the class of 1958 in February 1958 with former president Roswell G. Ham, who served the College from 1937 to 1957.

Once President Ham took office, the controversy that had played out in local and national papers over the preceding months immediately faded. Ham served until 1957 and is remembered today as a good and quietly competent president, one who enjoyed teaching more than administration. He captained Mount Holyoke quietly through the war years and after. He instituted changes gradually, shifting the life of the College away from the brownstone Gothic structures on College Street to modern brick residence halls constructed lakeside for a student body that, during Ham’s tenure, increased by 75 percent. By 1950, he quadrupled the men in a faculty that, under Woolley, had been 93 percent female.

Mary Woolley never witnessed these changes in person, though she had an opportunity to return to campus on multiple occasions. Just a year before her death, confined to a wheelchair after a stroke, she refused the honor of a professorship in her name—she could not, she wrote, until a woman was once again president of the College. Neither she nor her stalwart supporter Frances Perkins would live to see that day.

Years after Woolley’s death in 1947, Perkins expressed regret that her friend hadn’t softened her stance and accepted defeat with “good humor, sophistication, and fine manners.” But Woolley remains the College’s longest-serving president, and she is remembered for her legacy of empowering women to become intellectuals more than for her refusal to return to the College. She led Mount Holyoke through one of its most successful periods of growth and remains one of the most influential leaders in twentieth-century higher education.

—By Hugh Howard

Writer and historian Hugh Howard is the author of Mr. and Mrs. Madison’s War and the forthcoming Houses of Civil War America.

This article appeared in the fall 2014 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

October 15, 2014

Leave a Reply