Thirty Years of Red Ribbons

HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, continues to make headlines as activists and researchers mark the thirtieth year since the first HIV cases were identified—and the thirtieth year without a cure or vaccine.

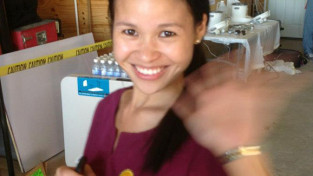

And the epidemic continues to spread, as Lily Rodriguez ’09 knows only too well. “The statistics are scary,” says Rodriguez, the HIV/AIDS prevention coordinator at the Utah Pride Center in Salt Lake City. “Here in Utah, HIV rates are still going up.”

For as long as HIV has been known, feared, and misunderstood; and as long as research on the virus has been underfunded and challenged; Mount Holyoke College alumnae have been part of the world’s battle against the epidemic. And their hard work is far from over.

Beyond the Comfort Zone

Mount Holyoke alums are represented on varying planes of defense against the HIV/AIDS epidemic. From counseling gay men on safe-sex practices, to advocating for women-controlled methods of safe sex and contraception, to distributing condoms and information to sex workers, they run the gamut on method and practice— but all are fully dedicated.

Lily Rodriguez’s first professional job was as an HIV/AIDS education and prevention coordinator. “I really didn’t have a clue about how write grants, how to coordinate groups for gay/bi men, and how to run a successful test site,” she recalls. But she learned on the job. Now—two years later—the HIV/AIDS prevention coordinator at the Utah Pride Center says she’s “really into it” and is proud of the work her team is doing.

Aleefia Somji ’09 volunteers with the Washington, DC, group Helping Individual Prostitutes Survive (HIPS). From 11 p.m. to 6 a.m., Somji rides in the HIPS outreach van, seeking drug users and sex workers. “We start conversations about safe sex and prevention and give people condoms, and sometimes we do HIV testing as well,” she says. “It’s intense. It’s definitely not in my comfort zone, but I’ve been learning so much from it.”

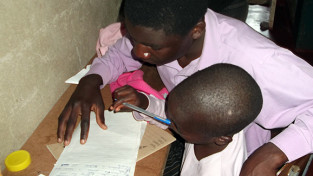

Prior to joining the Statistical Center for HIV/AIDS Research and Prevention, Laura McKinstry ’99 spent time in Zambia as an intern at the Centre for Infectious Disease Research, training healthcare providers to counsel tuberculosis patients about HIV. “When HIV attacks your immune system and weakens it, you’re no longer able to suppress the TB,” she says, explaining that the two ailments often occur simultaneously for this reason.

While “it’s extremely useful to do research,” McKinstry says that her work in Zambia “had a way more direct impact on people. Every little thing that we could do [left] them in a better place—more self-sufficient and able to continue the work. It felt good.”

The Personal Is Political

Tracie Gardner ’87 says HIV was brought home to her in 1985, when she lost a childhood friend to AIDS.

“I lost my childhood friend to HIV” in 1985, Tracie Gardner ’87 remembers. “I [had] sort of heard about it, but losing my friend brought it home. HIV was just background noise until then.

After graduating from MHC, Gardner made a beeline for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), a nonprofit—then in its infancy—designed to respond to the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. Gardner learned of the group while reading Randy Shilts’s And the Band Played On, an influential chronicle of the virus’s early days and its effect on the United States. As she was finishing the book, Gardner remembers saying, “I need to end up at this organization, GMHC.” And she did.

Gardner now is director of New York State policy at The Legal Action Center in New York City, a nonprofit dedicated to fighting discrimination against people with histories of addiction, HIV/AIDS, or criminal records, and to advocating for public policy that supports their work.

Other alums experienced a similar drive to work against the epidemic. “Someone who was HIV-positive came to our junior high and talked about HIV prevention,” says Laura McKinstry, now a project manager for the Statistical Center for HIV/AIDS Research and Prevention. “At the time, there was still a lot of stigma associated with HIV. What is HIV? Why does this man have it? [The speaker] left a big impression on me. It was dramatic and huge, in my small world.”

From that day on, McKinstry felt pulled into scientific research on HIV. “It’s one of the biggest public health issues of our time,” she says, and by working in this area, she believed she “could have a huge impact on the health of many, many people.” Her current work involves testing the safety and efficacy of medical interventions designed to prevent the transmission of HIV.

Mona Bernstein ’74 has been doing public-health work, including battling the HIV epidemic, since the first cases of AIDS were diagnosed in 1981.

Mona Bernstein ’74 was living in San Francisco in 1981 when the first cases of AIDS were diagnosed, and had many gay friends. “I was doing public health work, and [HIV] was major news.”

Bernstein was working with a women’s health collective at the time. “At Mount Holyoke, I read Our Bodies, Ourselves by the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, and it really opened my eyes to that whole perspective on healthcare,” she says. After college, Bernstein continued her experience and education in women’s and reproductive health at the San Francisco Women’s Health Collective, where, she explains, “the phrase we used was ‘the personal is political.’ I still feel that way.”

Bernstein now directs the Pacific AIDS Education and Training Center, a regional program serving California, Nevada, Hawaii, Arizona, Guam, and Samoa. “Our mission is to ensure that the clinicians are providing accessible high-quality HIV care,” Bernstein said. The center gives healthcare and social service professionals up-to-date clinical training and technical assistance so they can provide a better standard of care for people living with HIV or AIDS.

Aleefia Somji ’09 initially encountered HIV in a biology classroom, examining first the clinical side of the epidemic. HIV “is able to hide from your body’s immune system, which I thought was very intelligent,” she recalls. “I got interested from the biological point of view, but I really became interested in the social aspect—more specifically the stigma and discrimination—during my study abroad.”

She worked in India for the HIV Positive campaign, which aimed “to make people there positive about education, awareness, and support,” Somji says. “After that, I wanted to bring the campaign to Mount Holyoke, so I became cochair of the Student Global AIDS Campaign.”

Through that student organization, Somji fostered awareness of HIV/AIDS with free testing days, film screenings, and workshops. After graduation, she got a master’s degree from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, where, she recalls, her undergraduate minor in theatre proved handy. After learning about “HIV disruptive theatre” in India, she put it to the test in the London Underground transit system. “The point was to disrupt an audience—not tell them that you’re performing, but at the same time pass out information about HIV,” Somji explains. “Performers acted out conspicuous conversations about the transmission and treatment of HIV in the crowded Tube,making sure to mention where more information could be found.”

Now a research analyst at the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics, and Policy, Somji presented the abstract of her master’s thesis—examining correlations between alcohol use and HIV sexual-risk behavior in South Africa—at a summer conference of the International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research.

Finding a Way Forward

Successfully combating and ultimately conquering the virus in the future requires “a multilevel approach to controlling the epidemic individually and on a community level,” says Mona Bernstein. Since “HIV is an opportunist” and is not selective when it comes to race, gender, or sexual orientation, adds Tracie Gardner, “public policy cannot be one-size-fits-all.”

Gardner sees the epidemic two ways: “On the one hand, we’re looking at a chronic and manageable condition, like diabetes. On the other hand are the economics of a lifetime of being HIV infected—you need to take meds [forever] from the time you get your HIV-positive test to reduce your likelihood of transmitting it to others. We need to do more around prevention.”

“Testing people is a prevention method,” Bernstein notes. “It depends where you are, [but] 20 to 25 percent of people living with the infection do not know they’re infected. These people are infecting others. Research shows that once people find out what their status is, they decrease their risktaking behavior.”

Another key to ending—or at least stemming—the spread of HIV/AIDS around the world may very well be the education and empowerment of women. “When women aren’t educated, it weakens the community,” Gardner explains. “When women are strengthened and supported…when they are healthy, when they control their reproductive destinies, it tends to uplift the whole community.” Calling this a basic tenet of domestic and international development efforts, she says, “When the community is sick, it’s generally [true] that the women are not doing well.”

Gardner is a hearty advocate of women-controlled means of HIV prevention. “For thirty years, the best we’ve been able to provide is condoms,” she says. “We need quickly to develop ways that women can protect themselves without the consent, cooperation, or knowledge of their sexual partners. That’s when infections worldwide will be dramatically decreased.”

The HIV epidemic has had “a profound impact on the way healthcare is delivered in terms of patient rights, patient access to information, and patients being an integral part of their decision-making,” Bernstein says. “That came from the women’s health movement.”

Many activists and researchers hope that women’s education and empowerment can magnify the influence and reach of existing support and awareness programs around the world.

In the United States, Bernstein notes President Obama’s one-year-old National Strategy on HIV/AIDS. She says it “is looking at the many ways we can control the epidemic, [which include] reducing the number of people living with the disease, making care accessible and high quality, maintaining that high level of care, and addressing health-equity issues.”

“We don’t have a vaccine and we don’t have a cure, [but] we know a whole lot more now than we’ve ever known before,” she says. “I think we have cause for optimism, actually, but we do need the political will to go forward.”

Meanwhile, “there’s a lot of work that needs to be done,” Rodriguez reminds. Global statistics about the virus are sobering (see facing page), and funding is often tenuous at best. Despite the rising number of new infections, for example, funding for Rodriguez’s program was recently cut by $10,000. But fundraising efforts continue, as does the struggle against the epidemic’s tide and all that it brings, from discrimination and stigma to illness and isolation.

Mount Holyoke alums and dedicated others, however, hope that with commitment, advocacy, hard work, and a little luck, it won’t take another thirty years to bring hope and good health to the millions of people infected with, and affected by, HIV and AIDS.

—Hannah Clay Wareham ’09

This article appeared in the fall 2011 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

For more about alumnae working on the HIV/AIDS epidemic, visit alumnae.mtholyoke.edu/HIVat30.

March 30, 2012