A friendship that changed Mount Holyoke

In 1968, the city of Memphis, Tennessee, was at the center of the Civil Rights Movement. The movement and its leaders were in an escalating dispute between federal and state governments. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had set his sights on the city’s indignities against black sanitation workers who wanted fair wages, safe working conditions and equitable treatment following the crushing deaths of two garbage collectors. In February, 1,300 sanitation workers went on strike, crowding downtown streets and carrying “I am a man” placards. They stood toe-to-toe with police officers armed with dogs and pepper spray.

During this time, Rhynette Northcross Hurd ’71 left her hometown of Memphis to return to Mount Holyoke for the spring semester of her sophomore year. She was on campus April 4 when she learned that Dr. King had been assassinated. Rhynette, who is now a judge for the Shelby County Circuit Court in Memphis, was already committed to working for justice even before her time at Mount Holyoke, but it was in that moment of learning of Dr. King’s death that she felt the responsibility and certainty that her generation would be the ones to carry Dr. King’s dream forward.

A sense of duty

In 1967, during her senior year of high school, Rhynette was considering schools like Spelman College and Lake Forest College, but her brother, Thurman Jr., at the time a first-year student at Wesleyan, encouraged her to apply to Mount Holyoke. She recognized the school as one that “promoted academic excellence,” she says, but adds that the distance from home and the mounting angst of the civil rights struggles in Memphis gave her a sense of “trepidation” about attending.

“To be honest with you,” she says, “how do you get and encourage black people to come to a small town in Massachusetts that’s below freezing 90% of the time? Where are their friends going to be?”

Despite these concerns, she felt strongly that the fight was not just in Memphis — it was everywhere. And she committed to Mount Holyoke.

“I went to Mount Holyoke because I knew I would get an excellent education. But I also wanted to feel that my culture was respected.”Rhynette Northcross Hurd ’71

When Rhynette first arrived on campus, returning black students came around to each dorm, introducing themselves. They offered her a cultural connection at the College when it was overwhelmingly white in student body, faculty and administration.

“These women gave us advice on where to get our hair done, where to shop, where to eat, where to buy a coat to survive winters in Massachusetts,” she says. “They told us what professors they liked. They were really helpful, and it made settling in easier.”

In her first year at Mount Holyoke, Rhynette found herself in a school with “no classes about African-American history, literature — nothing from the diaspora. We had no black professors,” she says. Up until that time she had only had black teachers. “It was strange,” she says. “I went to Mount Holyoke because I knew I would get an excellent education. But I also wanted to feel that my culture was respected.”

Rhynette Northcross Hurd, left, and Deborah Northcross at Deborah’s home in November.

As she continued to find community and a sense of place, Rhynette reached out to her cousin Deborah Northcross ’73. They were the daughters of brothers, and at one point in their upbringing, their two families had lived together.

“She told me to apply and that I didn’t have a choice,” Deborah says.

In less than a year the two cousins were both undergraduates at the College, and they moved forward together with other black women on campus to bring the charge of the Civil Rights Movement to Mount Holyoke. It was, Deborah says, “a sense of duty.”

In the fall of 1968, Rhynette and Deborah joined the Afro-American Society, a new student organization on campus. (“Afro-American” was a popular term used in the 1960s by black Americans who wanted to self-identify as being of African heritage and American citizenship.) The group was in a coalition with chapters at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst and Smith colleges, and primary to their work was a movement to implement black studies courses at the colleges.

This was a critical time in black American politics and identity, as the Civil Rights Movement gave way to the Black Power Movement. The movement was reflected in the political organizing, rhetoric, clothing, styling and music of a culture that wanted to define and empower themselves on their own terms and negate any attempts to suppress their Constitutional rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

On December 12, 1968, the Afro-American Society staged a sit-in demonstration at Mary Lyon Hall, demanding a separate space for black students to meet.

“I remember we marched in [to Mary Lyon Hall], secured the building and had a sit-in,” Deborah says. “We didn’t know if we were going to be expelled or what. When it made the national news, my father called me and asked me, ‘Were you involved?’ and I said yes. He asked ‘Is that something you believe in?’ and I said yes, and he said ‘OK.’”

“He basically gave you the permission to go ahead,” says Rhynette, “Which I think is profound. It really speaks to Uncle Theron.”

A Memphis childhood

From a young age, Deborah made history in the desegregation of Memphis public schools after the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) asked her father, Dr. Theron Northcross Sr., one of the first black dentists in Memphis, to use the family name in a 1960 suit against the Memphis board of education (Northcross et al. v. The Board of Education of the City of Memphis, Tennessee). As the lead plaintiff, she would become a symbol of the equality promised in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that southern states like Tennessee fought to derail.

“I think when the NAACP asked my father if they could use his name on the lawsuit … that gave me an indication that he was a fighter,” Deborah says, “and it showed that he was a stalwart … for civil rights against injustices.”

When Deborah, who is now executive director of the U.S. Department of Education TRIO Training at the Southeastern Association of Educational Opportunity Program Personnel, was one of the first black students to attend Memphis Central High School, she remembers her father telling her, “You’re there to get an education. You’re not there to make friends. Just come home with a good education.”

As a Mount Holyoke student, Deborah called on the courage she had gained in her youth as she spoke out for her beliefs. She found herself returning to her father’s advice, knowing that he supported her actions. “I kept [his words] in mind,” she says. “In a sense, I was a fighter. I was prepared for some sort of tension, some sort of uncertainty. … And I didn’t know what to expect from day to day.”

After four days of student protest in Mary Lyon Hall, a special committee was formed, charged with establishing the Black Cultural Center in the Woodbridge. It was affectionately known as “The Black House” and was a home away from home for black students, according to Deborah and Rhynette.

The Black Cultural Center was an important step in meeting the demands of those students who had staged the sit-in. But it was only the first step, and the students continued to engage and make demands of Mount Holyoke College President David B. Truman. In 1969, Truman announced that a Black Studies interdisciplinary program had been added to the curriculum. It was another mark of success. And today Rhynette feels pride in the College’s efforts 50 years ago to respond to and support black students who spoke up. She also acknowledges that not everyone feels the same way.

“Some of our friends who were in school when we were there didn’t feel like Mount Holyoke supported them enough,” she says. “It was difficult. … Some could not break through and feel comfortable.”

Mindy McWilliams Lewis in May 2019.

What could have been

In 1971 Rhynette graduated, and Deborah, who had just completed her sophomore year, recruited her friend Mindy McWilliams Lewis ’75, P’05.

“[My brother] Thurman was the reason I came to Mount Holyoke,” says Rhynette. “And my being there was the reason Debbie came there. And Debbie being there was the reason Mindy came there. I’d like to think our coming to Mount Holyoke made a difference.”

Though Mindy and Deborah were high school friends, Rhynette and Mindy did not meet until 2000, through a chance encounter at an airport. Almost immediately, the three bonded, with Mindy as their leader and guide. She encouraged both Deborah and Rhynette to become even more involved with the College as alumnae, citing their trailblazing days as students and the need for that work to continue for the students of today.

“Leaving something better than it was found was always Mindy’s bottom line.”Deborah Northcross ’73

Until then Rhynette had been involved in the Black Alumnae Conference, held for the first time in 1973. Since that airport encounter, Rhynette has served on numerous committees for the College and the Alumnae Association and several terms on the Alumnae Association Board of Directors. She has been an alumnae trustee on the College’s Board of Trustees since 2016 and currently serves as a vice chair of the board.

Deborah, too, has served the College in many capacities, including as a member of her class board and of several committees, as vice president of the Alumnae Association Board of Directors, a trustee of the College from 2004–2009 and a member of the Alumnae Trustee Committee for the Alumnae Association. In 2003 she received the Alumnae Medal of Honor. And she was co-chair of the 2018 Black Alumnae Conference planning committee.

“Mindy was just amazing,” Rhynette says. “She was just somebody who looked at you — she’d give you that look, and she smiled — you knew she meant what she was saying and that you were gonna do what she asked you to do.”

The College leadership recognized these qualities as well, and in 2019 Mindy was named chair of the Mount Holyoke Board of Trustees after a lifetime of dedication to Mount Holyoke. The list of her volunteer roles and event attendance on behalf of Mount Holyoke spans nearly two pages. She started her Mount Holyoke work as a class agent and took on seemingly every possible role in fundraising and alumnae engagement over the course of the next three decades. Mindy famously referred to Mount Holyoke College as her “hobby.” A champion for diversity and inclusion, she had a long career working in development. And a long career serving her alma mater. After years of service to the College, including as a member of the Board of Trustees from 2006 to 2018, Mindy was ready to bring all of her experiences together at the helm of Mount Holyoke. Deborah and Rhynette could not have been more proud.

“Mindy was a person who just pulled good people together,” Rhynette says. “She’s like the glue. I would have loved to see the Mount Holyoke that she would have helped to create.”

In June, just a few weeks before Mindy was to step into her new role, she died unexpectedly. Her closest friends were heartbroken. The Mount Holyoke community was left wondering what could have been.

“When I think of Mindy today, I think of a young woman who proudly walked through the gates of Mount Holyoke, excelled in her studies and on June 9 took her wings — much deserved for the remarkable life she lived, exemplifying the lessons she’d learned,” says Rhynette. “To think that Mindy was just a little black girl from Memphis, Tennessee, who became the chair of the oldest continuing college for women in this country, and she never got the opportunity [to take the position]. … It is tragic in one sense that she never got to take on the role, but it’s been so meaningful that she had the opportunity.”

“[Our legacy] is that we made our parents proud and we served in some way,” says Deborah. “They were good servants, and I think they would appreciate that we were servant leaders and that we served the community in a good way.”

“And that we were kind to people,” says Rhynette. “We respected differences and were glad for them.”

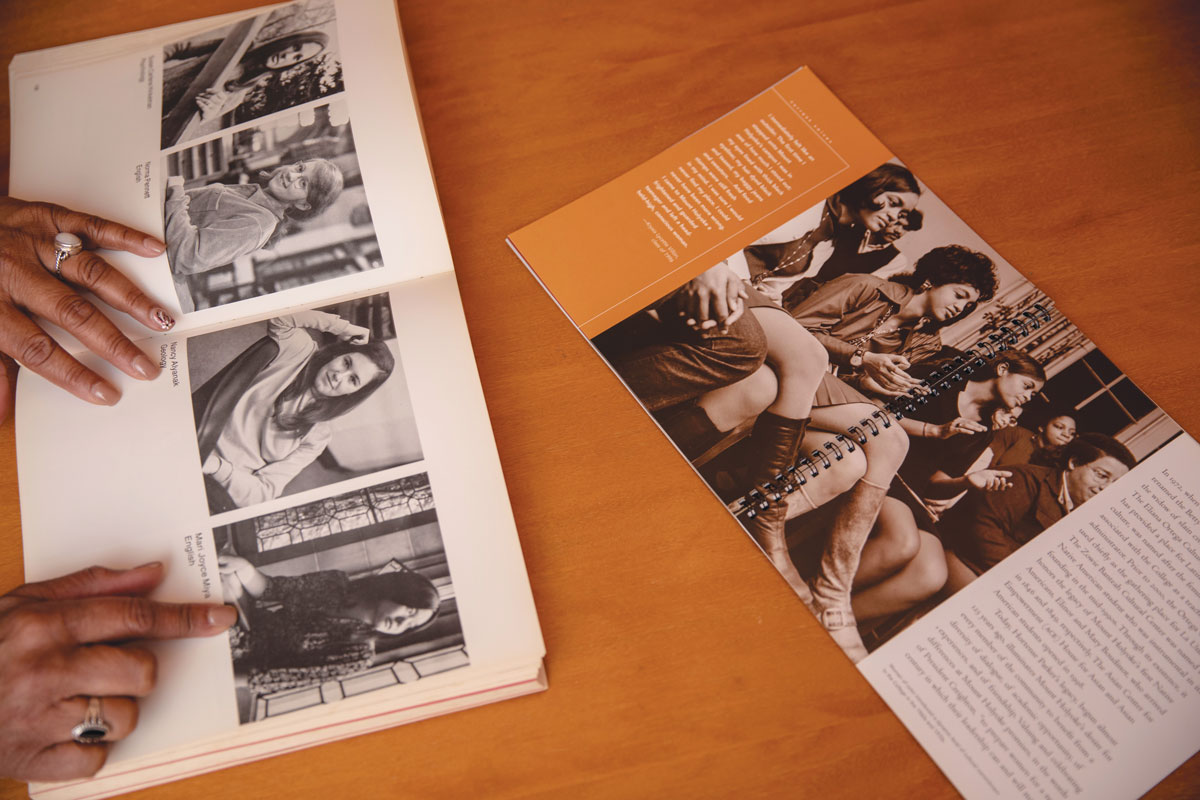

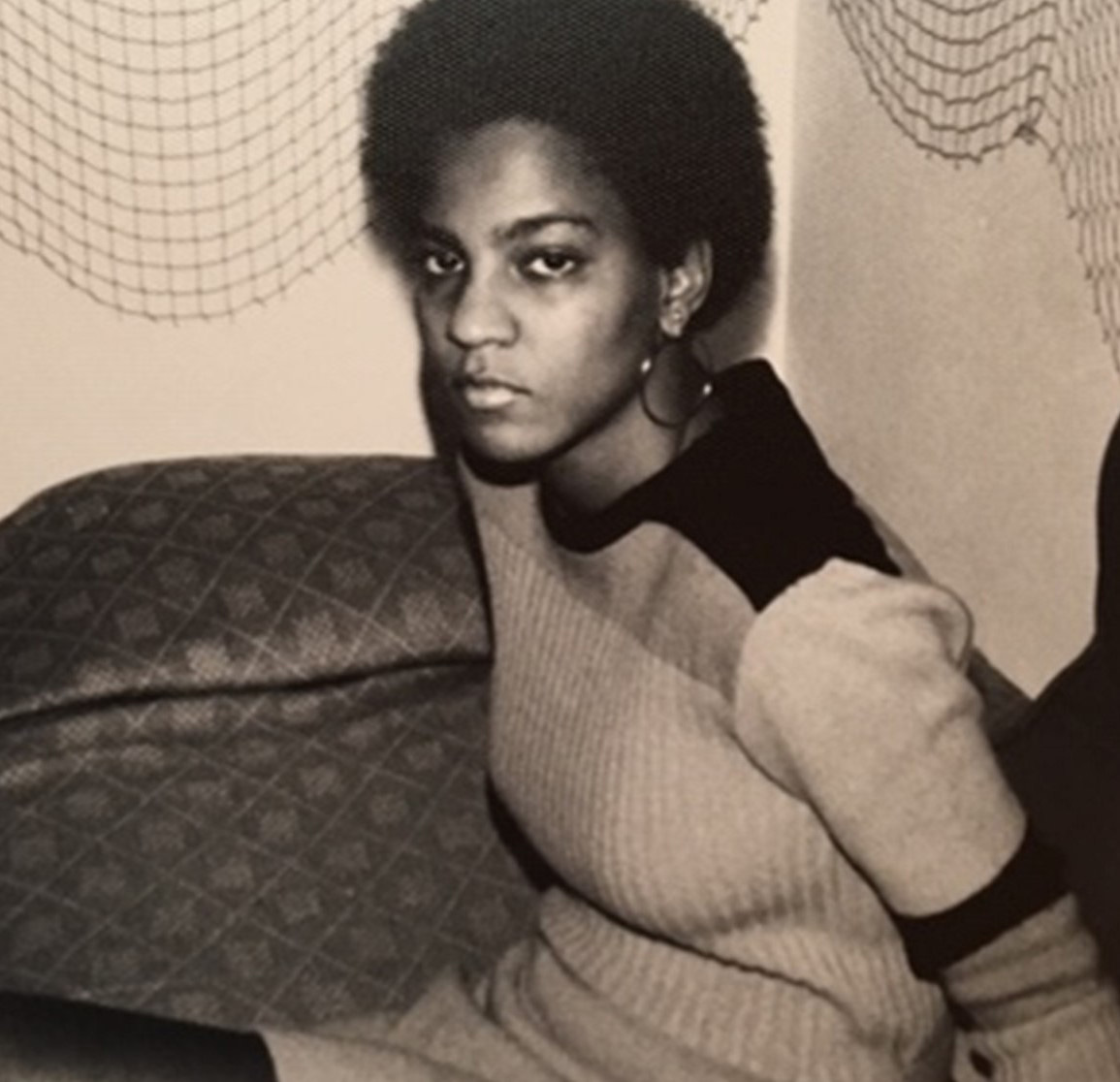

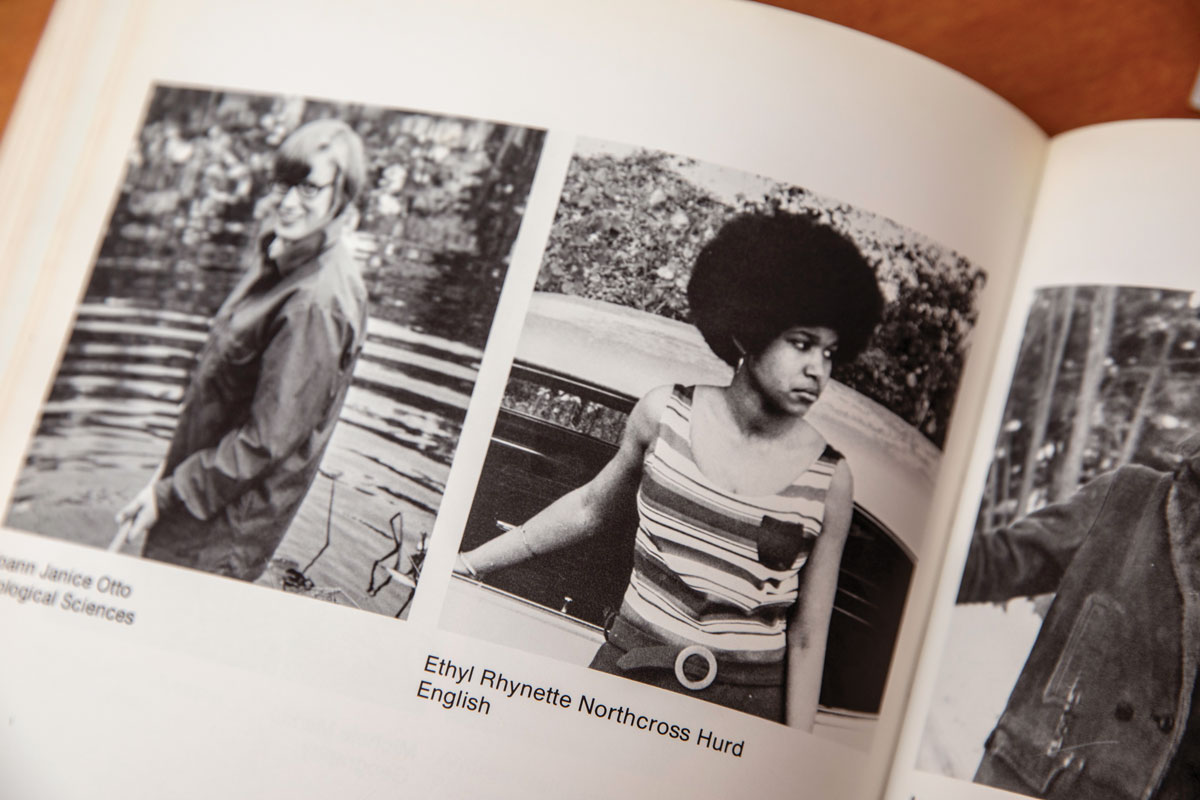

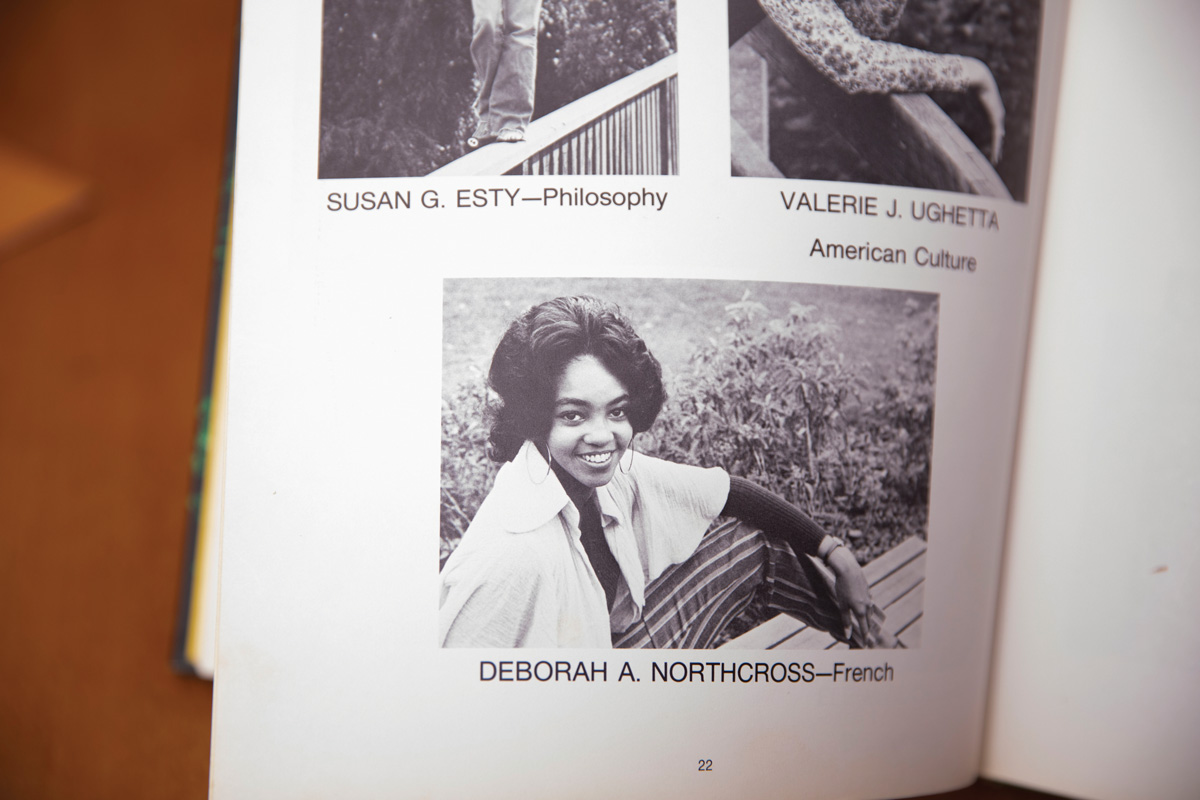

Cousins and friends since childhood, Deborah Northcross and Rhynette Northcross Hurd spent time together in November recounting their days as Mount Holyoke students, browsing through yearbooks and remembering Mindy McWilliams Lewis (fourth photo, as a student at Mount Holyoke).

Speaking at Mindy’s memorial service in August, Deborah recalled that Mindy had laser-focused vision when carrying out a project. “I found that to be true when working with her on the College’s Legacy of Diversity Committee during The Campaign for Mount Holyoke and on the Alumnae Association’s Black Alumnae Conference. You could say that leaving something better than it was found was always her bottom line.”

In September, when they gathered on campus for what would have been Mindy’s first meeting as chair, members of the Board of Trustees planted an oak tree on Skinner Green in her memory, a true symbol of her wisdom and keen vision for the College, in a central place where her legacy can be remembered.

“When I say we’re in a better place now, 50 years later, there is an awareness that we need to [continue to] meet those needs. We have more Afro-centric courses of study, we have begun to recognize what needs to be done to improve our hiring and curriculum design, we are moving forward,” Rhynette says. And in her role as vice chair of the board, and with the involvement of her cousin Deborah, she intends to continue to shape the path before her, to continue the legacy of three young women from Memphis whose work in South Hadley and far beyond the gates will have a lasting impact on generations to come.

—Written by Melonee Gaines

Melonee Gaines is a Memphis-based freelance journalist with The Crisis Magazine, theGrio.com, Carnegie and MLK50.com. She is also the owner of MPact Media Group, a digital media and public relations consulting firm.

—Photos by Andrea Morales

This article appeared as “Strength, Courage and Vision” in the winter 2020 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

January 30, 2020

Though I was not an alumnae I was proud to grow up in South Hadley. Particularly Mount Holyoke College. I was all of 11 years of age during the “sit in.” Just happy to bike my bike through the campus, play tennis. Loved every second. You captured that time in history so well. I was thinking to myself, look at what was happening and I had no clue! When I came to Florida in 1971 to live People would ask “Where are you from?” I would say, South Hadley where Mount Holyoke College is! Many folks just did not know of the College. I made sure they knew! My daughter had a project in school about “Important Women In History.” She did hers on Mary Lyon. RIP Mindy.

Well written article, I feel like I got an insight into these three alums, their sense of purpose and engagement. Makes me proud to be a MHC sister to the 3 Uncommon Women.

The single best article I have read in the Quarterly. Ever.

Read the artcle in the magazine first and again now on Laurel Chain. IMPRESSIVE!! I had the privilege of knowing Gloria Cochrane(class of 1951)who was a junior my freshman year in Brigham.

My only question “Is there a white students only” place on campus? Talk about equal opportunity? What a trail these three women blazed!! CONGRATULATIONS to them!!

Loved the story, especially since I know both Deborah and Rhynette, served with Deborah on the board of trustees, and met Mindy on a number of occasions. As someone who also came from the Jim Crow South to Mount Holyoke, I know that the story really captures what that transition was like, how the black MHC women had to create our own social structures in order to survive in this new environment, and how our relationships with, and support for, each other led to service to the college. Kudos to Deborah and Rhynette and Mindy!

I knew all three at MHC, living in dorms with each of them during my years at college. Rhynette and Deborah were always willing to engage on every level. Mindy was a wonderful person. All those who knew her either in college or after working as a trustee recognized her qualities.

This is a great article and brings back many memories of MHC, of these three ‘Uncommon Women’.