Unusually Grounded Alumnae Homes

These alumnae dwellings showcase their natural assets

Since the dawn of time, people have built homes to shelter themselves from the ravages of nature. And many in the developed world still choose to live in houses that insulate them from the natural world—super-airtight dwellings with central heating, air conditioning, and lots of interior space are the norm. But these alumnae have purposely selected homes that buck these trends. They’re compact—much smaller than the average American house size of 2,550 square feet—and each brings its residents into closer contact with nature.

Liv Cavallaro ’08

Liv Cavallaro ’08

Photo by Ben Barnhart

In Alstead, New Hampshire, Liv Cavallaro ’08 lives not within four walls, but in a circular yurt fifteen feet in diameter. Like those more typically found in the steppes of Central Asia, Cavallaro’s yurt is portable, with a wooden frame covered with fabric (in her case, canvas). She added a floor, skylight, and supporting cable, along with a woodstove, so it—and she—could cope with New England winters. “It’s really drafty, so I have to keep a fire going to be warm, but I like the air flow.”

“It’s really close to living outside,” she enthuses. “I can hear everything— the wind, the rain, the animals…the frogs started chirping two days ago.” A rooster periodically adds his crow to the animal chorus. This is a rustic existence, with an outhouse instead of plumbing, and water is hauled from a neighbor’s well. (She showers at friends’ homes.)

The yurt’s interior is nearly nine feet high at the center, tapering to four-and-one-half-foot outside walls. The inside space is divided by shelves into a cozy sitting area/library; a dining table that doubles as an art studio; a kitchen with propane stove, counter, and pantry; and bunk beds with storage beneath.

Cavallaro works at a preschool with a nature-inspired curriculum, grows some of her own food, and sells her artwork in nearby Brattleboro, Vermont.

The former community-house-dweller says, “Living in a yurt is an exercise in understanding my need for solitude and private space. I didn’t think I needed those things, but this is awesome!”

In 1976, Diane “Di” Howland McIntyre ’65 and husband Steve bought twenty acres to escape from their urban work lives in Silicon Valley. The property is dotted with redwoods, and boasts spectacular sunsets and views over the Santa Cruz Mountains. They first built a yurt for their getaway, but after Steve retired and retirement neared for Di, the duo turned part of a metal RV “barn” into a comfortable second home.

The McIntyres took pleasure in figuring out how to build an apartment from the inside out. It took four years, but now they have a fourteen-by-twenty-eight-foot space with a soaring ceiling. Di’s brainstorm was to use the upright girders as the framework for a Mondrian-inspired color scheme of black, white, yellow, red, and blue that “gives it a spark,” she says.

The interior has a sleeping loft, kitchen, and living room, with a bathroom out back. They used many recycled materials— the fridge came from an RV dump—though they “classed it up” with Ikea cabinets. Solar panels and kerosene lamps provide light, and the woodstove is stoked with logs from fallen trees.

The couple now lives primarily in Prescott, Arizona, but returns to their California retreat to enjoy the cooler climate and their many friends. “Coming from a congested area, having the opportunity to live in quiet is wonderful,” says Di. “It’s a counterbalance for the rest of our life.”

Few people would consider a seventy-two-foot-square dwelling spacious, but Mary C. Murphy ’05 does. That’s because she spent years sleeping in a one-person tent. “I’ve been a total nomad, moving every six months if not more often, working as a wilderness guide, trail worker, wilderness therapy instructor, whatever I found that looked interesting,” she says.

Few people would consider a seventy-two-foot-square dwelling spacious, but Mary C. Murphy ’05 does. That’s because she spent years sleeping in a one-person tent. “I’ve been a total nomad, moving every six months if not more often, working as a wilderness guide, trail worker, wilderness therapy instructor, whatever I found that looked interesting,” she says.

“I’ve admired the ‘tiny house’ concept for a long time, but I used to feel my life wouldn’t accommodate even a small house,” she says. But Murphy recently started a wilderness-trip business (mountainsongexpeditions.com), and a more permanent home now seems appropriate. “It’s a way of tricking myself into becoming more rooted,” she says. “I’ve spent many seasons living on the trail out of a backpack; life is so simple that way. I wanted to reproduce that simplicity in my house.”

Murphy’s central Vermont home functions completely off the grid. Half is a bedroom/living room and the other half is a kitchenette with a woodstove designed for a yacht, composting toilet, and solar panels to run her lights and laptop.

Murphy designed and taught herself to build the five-and-onehalf- by-thirteen-square-foot structure, using salvaged materials and the help of a few female friends. There’s not room for much, but that’s fine with her. “I feel weighed down when I have lots of things around me,” she says. “I love simplicity.”

The structure cost less than $4,000. “That’s about what I had in savings, so I didn’t have to wait for my dream,” Murphy recalls. “When I wake up in this place I built, I feel really empowered.”

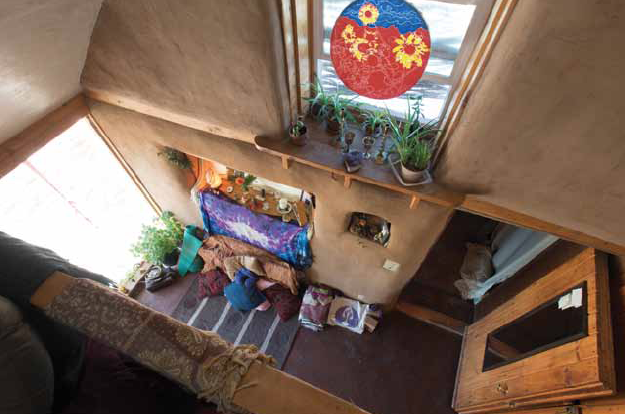

Home for the Rev. Sarah M. Sarasvati Cutler ’03 is a “straw-bale sanctuary” just outside Santa Fe, New Mexico. The timber-framed casita has a packed-earth floor and three-foot-thick walls made of straw bales covered in mud plaster. They insulate Cutler from the heat or the cold, depending on the season. A steeply angled tin roof provides full sun and passive solar heat in winter (a woodstove offers backup heating), and keeps the interior cool but dimmer in summer.

Home for the Rev. Sarah M. Sarasvati Cutler ’03 is a “straw-bale sanctuary” just outside Santa Fe, New Mexico. The timber-framed casita has a packed-earth floor and three-foot-thick walls made of straw bales covered in mud plaster. They insulate Cutler from the heat or the cold, depending on the season. A steeply angled tin roof provides full sun and passive solar heat in winter (a woodstove offers backup heating), and keeps the interior cool but dimmer in summer.

The snug cabin contains a small kitchen, sleeping loft, common area, and bathroom. She’s also made space for a bodywork studio (Cutler does craniosacral therapy and is studying massage) and shelves full of dried herbs for a nascent tea enterprise (see laughingtreespace.com). Outside is a curved retaining wall that shelters a garden—the heart of her sanctuary.

Cutler moved here two years ago from a typical suburban house, but it was time spent living in a tent at the Lama Community north of Taos that anchored her desire to live in a “natural” house. “Because it’s connected to the earth, the house provides a calmness and simplicity that really speaks to me,” she says.

—By Emily Harrison Weir

This article appeared in the summer 2013 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

July 18, 2013

This is a most interesting article!! My husband and I prefer small, also, but we’re living in a comparatively spacious 875 square foot space. It’s much better to have more outdoors to enjoy!!

I pass Mary Murphy’s house on my way to rehearse/perform at QuarryWorks Theater in Adamant, VT (quarryworks.org). Now I know who lives in that neat, cute structure. Currently I’m playing a homeless woman who breaks into a storage shed in a Maura Campbell (Maura’s daughter Amanda Smith Englund is a MHC grad) play called “Open Me Last.”

Once again the intricate Mount Holyoke connection manifests its web.

Mary, can I knock on your door? I was some activity last night around your home. Come see the play! Tickets are free! Carol

i would love to see the script for this play! is it available anywhere???? thanks!

Wow, what great homes! And a cool story! Thanks, Emily.