Essays of resilience by Mount Holyoke alumnae

About a year ago we launched an essay contest, but the idea had been percolating around our office for a while. We talk often during meetings about how to share more alumnae voices in the Alumnae Quarterly. And about how to include more personal stories that will resonate with our diverse readership. Last summer we decided to turn that question to you, our readers. We gave you a theme: Resilience.

About a year ago we launched an essay contest, but the idea had been percolating around our office for a while. We talk often during meetings about how to share more alumnae voices in the Alumnae Quarterly. And about how to include more personal stories that will resonate with our diverse readership. Last summer we decided to turn that question to you, our readers. We gave you a theme: Resilience.

Here we share two essays from those submitted during the six months that the contest was open. They were selected by a team of five readers — two magazine staff members and three alumnae volunteers who serve on the Alumnae Quarterly committee. The selection process was blind, with names and class years of each entrant revealed only after the process had been concluded.

We are grateful to everyone who submitted their work and hope to offer another opportunity for you to do so in the future.

—Jennifer Grow ’94, editor

Staring Down the Universe

At 28 years old, I sat on the beige carpet of the house I had lived in during high school, leaning against the couch, next to my mother, watching her die.

Seven years earlier, I walked the short distance from Ham Hall (then the international dorm) to the stage of the Gettell Amphitheater in my crisp, new, white cotton dress, grinning as then-college president Liz Topham Kennan ’60 handed me my diploma with the customary handshake. From the far-back benches, my mother, younger brother and grandparents applauded me, the oldest and first of my generation to graduate from college. Two shadows tinged my supreme happiness: my father’s absence — my parents having divorced during my first year; and my mother’s struggle to accept the “nerdiness” — her words — of her biologist daughter. That day, though, we put aside our differences. After the ceremony we gravitated to the winding paths lined with crayon-colored tumbles of blooms behind the greenhouse and snapped family photos by the koi pond.

Now, my world had shrunk to a stuffy, dimly lit room in a modest colonial house in a New England town where a hospice nurse sat at the ready day and night. Upstairs, in a narrow guest bedroom mostly filled by a stiff antique bed, my worldly belongings, stuffed in suitcases and cardboard boxes, covered the floor. Within the boxes, in a red tube, lay my doctoral degree in anatomy and neurobiology from Boston University School of Medicine. All the hours of tracing blood vessels and nerves, of running my fingers over rough sutures defining sections of the human skull, were utterly useless.

There was not one piece of knowledge gained in my 100-hour weeks of studying medicine that would save my mother.

Whenever I was not sprawled on the floor in silence watching my mother breathe, I crept upstairs to my computer to scroll through job ad after job ad. Weeks earlier, when I had received the call that my mother was dying, I was nearing the end of a one-year teaching contract at a New Jersey college. The year before, I’d completed two years of postdoctoral research on Alzheimer’s disease, during which I’d fallen in love with a fellow scientist, and spent a month traveling Hong Kong and Macau with him. But, we had ended the relationship when he returned to Hong Kong for good. I was newly alone and at a career crossroads, veering away from research, yet not sure where I was headed. The country was in a modest recession. Jobs were scarce. When the call came, there was nothing keeping me from returning home to share my mother’s final days, bringing all of my belongings with me.

As I leaned against the couch, watching my mother’s chest rise and fall each day, not entirely sure that it would (hoping that it would, yet also hoping that it would not, and that she would be released from the constant grinding pain), I floated, untethered, unsure of who or what I was, almost feeling like I didn’t exist. Each day, listening to my mother’s rasping breath, my identities were stripped away one by one: scientist, girlfriend, daughter, until nothing was left but a pure essence, a spark, suspended.

What was left was me, alone, disconnected, seemingly nothing. I could blow on the spark, believe in myself enough to grow past the crushing pain of being stripped bare day after day. Or I could do nothing.

I discovered, slowly, that I refused to be crushed. The spark, fueled by a hard kernel of will, flared, fanning into flames.

Out of this a voice grew that simply said, “No.” No matter how stripped and laid bare, I stood up from slumping on the floor all night, holding my mother’s hand, and walked upstairs to the computer. I had graduated with degrees that my mother didn’t understand. But still, I wanted to succeed. And I knew she would want me to as well. Once again, we had put aside our differences, and my mood began to shift.

I sent cheerful, earnest cover letters about my interest in the advertised jobs. I sent them day after day, month after month, the marigolds and impatiens of summer withering, browning, finally vanishing, erased by snow. While other families were giving thanks and tucking into turkey and gravy, I held my mother’s hand for the last time, with my stepfather, and my grandparents and aunt clustered around. The day after the funeral, I packed my boxes to move in with my new boyfriend, whom I later married. Another spark had turned into flame.

Near the start of the New Year, the endless “Nos” finally turned to “Yes,” and I regained my membership in the club of the employed, becoming a vice president at a venture-backed startup. A year after that I was promoted, and by the end of my second year, I was generating $4 million in revenue from nothing. I had learned the meaning of grit, the essence of resilience. To simply live — even without my mother — defying the universe.

Candice M. Hughes ’86 leads the consulting firm Hughes BioPharma Advisers, working with a third of top biopharma firms, managing corporate alliances and supporting regulatory affairs. An accomplished storyteller, her poetry and creative nonfiction have been published in The Allegheny Review and The Lyon Review. She is a recipient of the Mount Holyoke College Ida F. Snell Poetry Prize and a Pen Works Honorable Mention for Creative Nonfiction. She is the author of two novels, “Dead Evil” and “Death on a Thin Horse.”

Candice M. Hughes ’86 leads the consulting firm Hughes BioPharma Advisers, working with a third of top biopharma firms, managing corporate alliances and supporting regulatory affairs. An accomplished storyteller, her poetry and creative nonfiction have been published in The Allegheny Review and The Lyon Review. She is a recipient of the Mount Holyoke College Ida F. Snell Poetry Prize and a Pen Works Honorable Mention for Creative Nonfiction. She is the author of two novels, “Dead Evil” and “Death on a Thin Horse.”

Trinity of Resilience

I am an unwilling expert in resilience.

In 2005, five months before our wedding, my partner, Laura, suffered a significant brain injury. Though she eventually recovered, my memories of our first year of marriage are of my wife’s flat affect and impaired memory, instead of sweet nothings whispered at bedtime. We regained our footing, only to have our infant son, Simon, diagnosed with acute congestive heart failure in 2008. After four months in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), we were released to the brutal reality of parenting a gravely ill, tube-fed baby with a very uncertain future.

I am not the same person today as I was before these events, but I am happy.

In the early years, I could not have imagined happiness would be possible. Three things helped me move from surviving to thriving: receiving, rejoicing and releasing.

Immediately after both incidents, a tsunami of help came rushing to our doorstep. My first instinct was to try to do everything myself. However, Laura and I quickly realized that receiving and accepting whatever people offered us was the sunlight that would help us photosynthesize trauma into a life. We said yes to everything, no matter how uncomfortable it felt. The result was lasagna and dog walks, and rooted relationships to hold us upright when fear and trauma threatened to knock us down.

Receiving meant accepting help in ways I never could have anticipated. As Seven Sisters grads in our mid-30s, my wife and I never imagined needing ongoing financial assistance from our parents, but we did, and we took it, gratefully. When I found myself ground down from the unrelenting anxiety and depression of parenting a child with a life-threatening disease, I finally accepted a prescription for an antidepressant medication. It was one of the hardest and best self-care decisions I’ve ever made in my life. I made it so that I could thrive.

We learned to rejoice whenever possible.

Our second day in the ICU, “A Brand New Day” from “The Wiz” started playing on the iPod we brought with us. Locking eyes, Laura and I started dancing, and as we silently shimmied around the isolette that held our baby’s tiny unconscious body, connected to a respirator and two poles of intravenous medication, we shared a tearful smile. Our resident physician watched our silent revolt against death, and then, a few beats later, joined in.

I grabbed every shiny nugget of joy that caught my eye. We threw ourselves a wedding at the hospital. Yes. Really. Facing the prospect of California’s anti-gay-marriage initiative, Proposition 8, we needed to get legally married, because our formal, glorious wedding held three years prior wasn’t legally binding. So the tuxedo and wedding dress came out of storage, and we got married again in the hospital courtyard, accompanied this time by Simon. And an IV pole.

Releasing my hold on what things “should” look like is probably the most valuable thing I’ve learned about surviving stress and trauma.

My notions of what a first year of marriage “should” look like eventually had to go, because I would never have that. Simon’s diagnosis required me to slowly release my vision of a typical child and embrace a new normal. It took a few years, but I eventually learned that pining for something that can never be only leads to misery.

For years, just keeping my head above water felt like a triumph. But it turns out there was more for me than just getting by. I still adore my wife. Parenting feels more like fun than work. Perhaps most important, when someone asks how I am, I can honestly, joyfully reply, “great!” By learning to receive, rejoice and release, I’ve been able to create a life that is more than bearable. It’s a miracle.

Jaime Jenett ’97 lives in Oakland, California, with her wife, Laura (Smith ’95), and their son, Simon. Inspired by her innumerable experiences of kindness and compassion on her journey parenting Simon, Jaime started the nonprofit Tikkun Rising to support Tikkun Tokens, the kindness recognition project she launched on her 40th birthday. Learn more at tikkuntokens.org.

Jaime Jenett ’97 lives in Oakland, California, with her wife, Laura (Smith ’95), and their son, Simon. Inspired by her innumerable experiences of kindness and compassion on her journey parenting Simon, Jaime started the nonprofit Tikkun Rising to support Tikkun Tokens, the kindness recognition project she launched on her 40th birthday. Learn more at tikkuntokens.org.

This article appeared as “Essay Contest” in the summer 2018 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

By the numbers

Here we share a little bit about the process of the contest and the alumnae who participated.

34

Total number of submissions

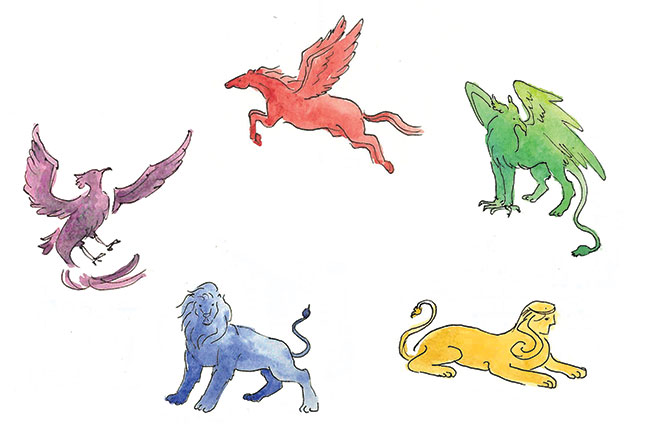

Class animals of writers

9 blue lions

11 green griffins

3 yellow sphinxes

9 red pegasi

1 purple phoenix

12

Number of essays dealing with illness, disability or injury

1

Number of alumnae who submitted poetry

45

Percentage of essays mentioning Mount Holyoke

11

Number of essays written by alumnae who graduated in 2000 or later

2/3

Fraction of essays submitted from writers who graduated before the year 2000

52

Percentage of essays submitted in the two weeks before the December 15 deadline

5

Number of alumnae and staff who served on the selection committee

1983, 1986, 1994, 2009

Graduating years of alumnae who served on the selection committee

August 2, 2018

Leave a Reply