Is Alternative Medicine Good For Your Health?

Abby Greiner ’96 learned about holistic medicine from her horses. While in her twenties and pursuing a career in dressage, she sought equine treatments that were natural and safe. “My first horse had arthritis, loved acupuncture, and was less stiff after treatments,” she says. “My second horse hated acupuncture, but chiropractic and homeopathy worked for him.”

She “came fairly close to the top” of the dressage circuit, “but my life was unbalanced.” Working to pay for lessons, room and board, and the upkeep of her horses, she “just about broke even.” On top of that, she developed carpal tunnel syndrome from years of sweeping stalls and shoveling manure.

“I went through a spell where I was taking Advil pretty much all day,” she says. “Some days I’d walk around with ice packs taped to my wrists. My next options were cortisone and surgery. I was amazed at how effective holistic medicine had been for my horses, so I tried it myself.”

After seeing a chiropractor, Greiner says the pain went away but not the nagging doubts about her future. “Being a groomer for horse trainers is a young person’s profession. Holistic medicine seemed like a better fit as I got older. I wanted balance in my own body, and I thought it would be good to help others find theirs.”

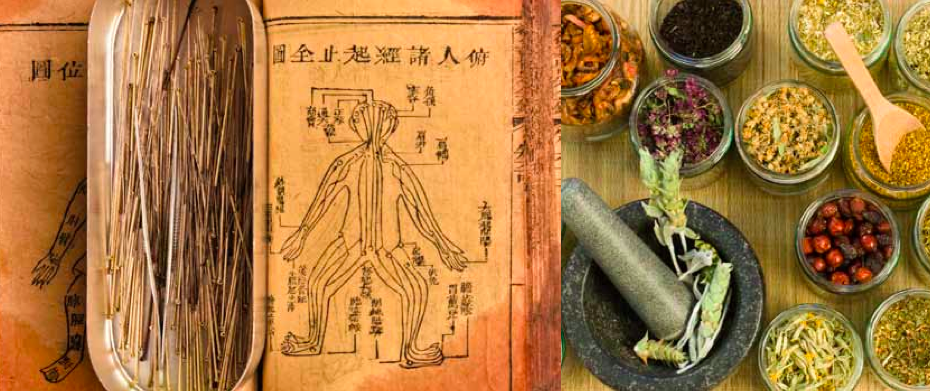

Today, Greiner is a master of acupuncture and oriental medicine and works out of a chiropractor’s office in Framingham, Massachusetts. She is in good company. At least twenty MHC alumnae have similar career trajectories–not surprising, says Greiner, because the college “has a really good science program.” They are part of a growing cadre of health professionals who practice “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM). Also labeled holistic, natural, New Age, or nontraditional medicine, it is called “complementary” or “integrative” when used with Western, or allopathic medicine, and “alternative” when used instead of mainstream medicine.

Like Greiner, many other alumnae CAM practitioners discovered the field as patients. For example, Karuna (Ramona) Sabnani ’97, a Wall-Street-bound international relations major, had “weird pains in her back and leg” as an undergrad. “I started getting better when I was treated by a chiropractor and Shiatsu practitioner,” she says, noting that “both were foreign modalities to me at the time. I was told how my eating was affecting my body and how the stress was contributing to my pain. None of this was even considered by allopathic doctors.”

Admittedly, alternative medicine is a constantly changing, still controversial, and often confusing universe. Ancient healing systems, such as Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine, that are accepted as mainstream in other cultures are grouped in the United States with newer modalities, products, and devices. And yet, four out of ten Americans turn to CAM to reduce stress and combat disease. Women with higher education and higher income are the biggest users. Since 2002, therapies involving deep breathing, meditation, massage, and yoga have seen the greatest growth. This is partly because an expanding body of scientific evidence suggests that such modalities are effective.

“Science is being brought to these areas,” explains Josephine Briggs, an MD and director of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), which has been part of the National Institutes of Health since the early 1990s. “We rely heavily on evidence-based studies—not a single study, but a review of the entire literature.” The center educates the public, supports researcher training, and funds studies at medical facilities where CAM is used to augment traditional treatment.

What’s CAM good for?

Perhaps this sea change is long overdue. In the last half century, health problems in this country have shifted from infectious diseases to conditions you live with. Half the adult population, according to the Centers for Disease Control, suffers from at least one chronic illness—an ailment for which traditional medicine is not always effective. At the same time, the mandate for doctors to lower costs translates into office visits lasting twenty minutes or less. Studies cited by the National Hemophilia Foundation show that MDs interrupt patients’ initial statements after twenty-three seconds on average and spend a single minute providing information.

In contrast, the alumnae practitioners interviewed by the Quarterly schedule at least ninety minutes for first visits. CAM patients say it’s a relief to talk to someone who sees you as a whole person instead of being bounced from one medical specialist to another, and given pills instead of attention or advice. Whether a patient walks in complaining about a rash, a headache, or heartburn, a CAM practitioner will look beyond her skin, head, or stomach. “I really listen to their history,” explains Kimberly Iller ’99, a naturopathic doctor in Seattle. “I ask about their parents, where they live, what kind of job they have, what they think about their illness, and what they believe to be the cause, not just what medicines they’ve tried.”

No surprise, then, that formerly unconventional practices, such as meditation and relaxation techniques, are now offered at revered health institutions, including Harvard and the Mayo Clinic. This trend is likely to continue as other therapies are proven effective. Briggs cites a partial list of “promising” areas of research, including pain management for conditions such as fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, and back pain; fish oil as an anti-inflammatory; and the use of physical strengthening, yoga, and breathing techniques for postmenopausal symptoms. (Read more information.)

Although some use CAM as a preventive measure, the most common reasons for seeking alternative practitioners are pain and anxiety. “Most of the patients I see feel like they’re losing their quality of life and that there’s no one else to help them,” says Iller, who shares an office with an MD who studied acupuncture and sometimes prescribes herbs. “We work quite well together, but most other MDs treat me as if I’m not a real doctor.”

Sara Burks Ohgushi ’85, a midwife and naturopathic doctor in Portland, Oregon, who was drawn to naturopathic medicine when she had her first child, adds that many of her patients would be considered normal on conventional lab tests. “There is no diagnosis code for an exhausted mom who hasn’t felt good since she had a baby or someone whose adrenal glands have been stressed out by an abusive relationship. Mainstream medicine is the perfect thing when you break your arm or your appendix bursts, but [CAM] is about consumers understanding that they have other options.”

Critics of CAM claim there’s only limited evidence that these “fringe” practices are effective. They point out that patients are a self-selected group, disillusioned with mainstream medicine in the first place. “Success,” detractors claim, is due to the placebo effect: merely spending time and building trust makes patients think they’re better.

However, disease is a complex mix of physical, social, psychological, and spiritual factors unique to each person. It’s hard to tease out cause and effect or to apply Western thinking to ancient healing practices. It’s even more challenging to measure trust and hope or the depth of connection between patient and practitioner—elements that, even critics acknowledge, promote healing. In the final analysis, if you feel better, does it really matter why?

—By Melinda Blau

This article appeared in the winter 2012 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

February 13, 2012