My Voice: 50 Years After The Feminine Mystique, Have Women’s Choices Changed?

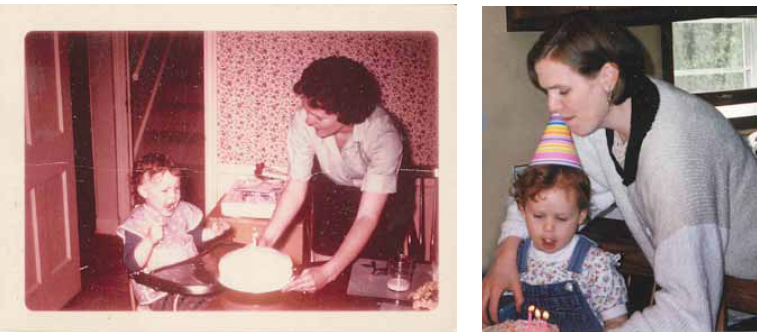

The life choices available to Meredith Casey (left) are quite different from those open to her mom (Cindy Carpenter ’83, center) and grandmother (Mary Lou Judd Carpenter ’55)…or are they?

I first read Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in college. It was the early ’80s, and when I came home for winter break, I mentioned to my mother that I had found the book interesting. Her response: “That book changed my life.” I found out later that it had probably changed my life as well.

I was two when Friedan’s book was published in 1963. My mom—Mary Lou Judd Carpenter ’55—was at home with her small children while my father, an attorney, worked. I grew up in the world Friedan described: well-educated, competent women who married well-educated, professional men and found themselves at home with their children. I didn’t experience my mother as unfulfilled, but I do know the message my sister and I received was very clear: You are to have a career. You are to go the places I did not. You are to look at traditionally male endeavors as opportunities open to you.

My mom contends that she just wanted us to be aware that we had choices, but neither my sister nor I heard it that way. We heard that getting married and having children were part of life, but careers were most important. We were not to be dependent on a man, live for our children, or be the default keepers of home and hearth. We were to have careers, financial wherewithal, and independence. This didn’t seem inconsistent to us—we were growing up right along with the women’s movement—and both parents expected us to develop our intellectual and vocational potential. My father spoke admiringly of new women associates; my mother shared examples of young women pursuing graduate work or making it as young executives. My peers and I assumed we would have some sort of career, and many of my classmates had very clear professional aspirations. I marched out into the world with paisley bow-tie and sensible pumps, naively assuming that I would add the family piece along the way.

My reality included all the well-documented challenges faced by working women raising children and managing families. My friends and I lamented how we enjoyed feeling capable at work, but hated feeling short-changed at home. Many of us had been raised by stay-at-home moms, and we aspired to create family lives based on a labor model we didn’t have. Our employers, colleagues, partners, and we ourselves ad-libbed a variety of solutions. Part-time, flex-time, freelance, contract, job-share, even the “mommy track”—all offered only partial solutions and all came with trade-offs.

Left: Mary Lou Judd Carpenter ’55 serves birthday

cake to two-year-old Cindy in 1963.

Right: History repeats itself as Cindy Carpenter ’83, now the mom, celebrates daughter Meredith’s birthday.

This “You have choices” deal didn’t feel like a deal at all. As I juggled work and family, my mother’s life sure looked OK to me: she ran a household, volunteered for causes she believed in, and spent a lot of time with interesting, competent women. She made significant contributions without ever stressing about a paycheck, a promotion, or a performance review. Mom’s carpools ran with precision; her dinners were nutritious and on time; sick children were simply brought along to committee meetings. I know being home with children is uniquely challenging, so I am not minimizing the stress, but I’d wonder whether my mother’s route might have actually gotten me closer to what I wanted: time with family, work I believed in, and the ability to make a meaningful contribution to the world.

This has really come home to me as I raise my daughter, Meredith. She has watched me do the working mother twostep, and once told a teacher that she wanted to be a “client” when she grew up—after all, that’s what Mommy talked about, so it must be important. At age seventeen, she has seen great variety in how families manage work and childcare, and she doesn’t have strong opinions about one way being preferable to another. But what my mother thought were opportunities for me look like purgatory to my daughter. She doesn’t see my career in corporate communications as something to aspire to, although she accepts that it’s important to me and necessary for our family. But what she values from her childhood are the rituals, events, and gatherings that were the first items cut from my to-do list when I ran out of time or energy. I know she would have liked to have a family life more like what I had growing up. Yet, as she prepares for her own future, she is eager to pursue her own passions, and doesn’t view the “home front” as gender-specific territory. She may be no better equipped than I was to understand what the trade-offs really feel like. What am I to tell her about “choices”?

Friedan’s book remains very important, and I don’t want to diminish the problems it portrayed and the challenges that still exist today. I am grateful for the choices available to me and the support I had from my mother and others. I know my daughter has many more options and opportunities because of the women who came before her. But the message I want to impart to her about the choices we have is more qualified and nuanced. I don’t feel the confident conviction that I heard from my own mother: pursue a career you love and the family life you want. My daughter’s world is very different than mine or my mother’s, but I wonder whether the ambivalence I sometimes feel will diminish with successive generations. We’ll have to wait another fifty years to know.

—By Cindy Carpenter ’83

This article appeared in the fall 2012 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

August 13, 2012

Fifty Years after The Feminine Mystique: More Choices, Same Challenges

A few years ago I read The Feminine Mystique and was struck by Friedan’s description of a kind of situational depression or turmoil that female leaders encounter when they become mothers. As uncommon women we are used to managing multiple responsibilities with poise and grace. When we become mothers life gets messy.

In her book, Betty Friedan references a survey given to Mount Holyoke alumnae. I was curious, so I contacted the archives for help in tracking down the survey. As the college prepared to celebrate 125 years, the Quarterly published a series of articles based on the alumnae survey. I couldn’t believe the similarity in feelings and challenges that women expressed then and that women still face today. Elizabeth Montignani Guest ’34 shared a story about a debate with Amherst College that took place in 1932.

The topic was “Resolved: That a Woman’s Place Is in the Home.” We, of course, took the negative. With the verve of Bloomer Girls we pleaded for the emancipation of women. With our college training we should go forth to pursue careers in government, business, sciences and the arts. Not for us the drudgery of the home! If we deigned to marry, we begged for household help to do the menial chores and care for possible children. Free us, we cried, to develop our talents and better the world. So eloquently did we argue our points that we won a unanimous decision from the judges, and the world waited to follow my career. What happened? I married an Amherst man and settled down to domesticity without ever having earned a penny except as a babysitter.

We continue to be torn between our need for challenging work outside the home and the realities of raising children or caring for family members.

Betty Friedan later retracted her statement that we could “have it all.” But maybe we can “have it all.” Professor Fran Deutsch published a book called “Halving It All” in 1999 where she argues that couples who share caregiving responsibilities as well as responsibilities for contributing financially to the household are more likely to be satisfied with both their personal and professional lives.

Here’s the tricky part. We need work cultures that focus on results rather than face time. In the March/April 2010 edition of the Solutions Journal, Rachel Barbour ’89 and I argue that workplace flexibility policies are not working because they are incongruent with our accepted model of work. Our socially accepted “ideal” model of work still assumes that a worker does not have time constraints or caregiving responsibilities. Therefore we need a new model of work. So, we created one. It is called the Accountability Model and it assumes the following:

1. That all workers have caregiving responsibilities (care for oneself, for others and for our communities)

2. That all workers will need to adjust the time they spend doing paid and unpaid work at various stages of their lives

3. That all workers are responsible for achieving desired outcomes

To address the challenges that still exist today, we need two paradigm shifts to occur. We need to change our beliefs about the ideal worker and about men’s roles as caregivers. The first requires transitioning to the Accountability Model of Work and the second requires us to support men’s roles as caregivers. I truly believe that when these paradigm shifts occur, we may “have it all.”

Amy Brown ‘90