My Voice: On Hearing, in Fragments

Growing up, I never knew what was happening onscreen when I went to the movies. As I sat beside my friends, I would mimic their reactions—laughing when they laughed, calling up a tear at the moment in My Girl when I finally realized the boy had died. I was at the theater because that’s what we did together in the small town where I lived. But while I could sense what characters on screen were feeling through the actors’ body language, I could never fully participate, because I am profoundly deaf and rely primarily on lipreading.

I was diagnosed at just over a year old. This was 1981, and schools for the deaf had not yet gained attention as a source of education or community. When it came time for me to enter kindergarten my parents were encouraged to mainstream me into the public school system. I was given hearing aids and taught sign language so I could follow the interpreter at the front of the classroom. Despite my obvious difference, I strove to fit in, quickly learning that “yes” or “mmm” was the answer to most things. In real life and at the movies I learned how to develop the correct response to situational cues without knowing the content of what was happening. At the time that was often enough for me.

Attending Mount Holyoke, with its focus on intellectual growth and feminism, made it easier for me to seek out friends who were accommodating of my deafness. But even then, I did not ask much of them or of myself. I continued to perform as hearing, often unconsciously. At various points during college, I halfheartedly attempted to integrate into the world of American Sign Language, where members of Deaf Culture have created their own history, beliefs, and understandings of disability. But I never quite fit in, because I still preferred speech to signing. I saw my deafness as an impairment rather than as an identity.

The option of passing as hearing had provided me with a sense of privilege.

Katie Wagner ’03

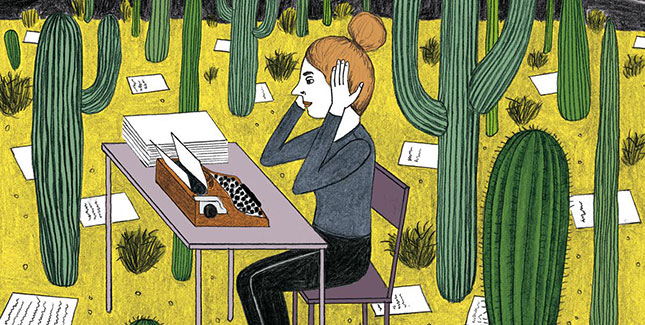

After graduation I pursued a master’s in creative nonfiction writing. In the hot desert of Arizona, I began to write about my experience of deafness; about sounds just outside of my reach; about deep isolation; about the intersection of queer and deaf identities. Yet I began to understand that my writing was unconsciously geared toward making hearing people feel comfortable about my difference. It wasn’t until my early thirties, when I entered a doctoral program in clinical psychology, that I was finally able to confront the tensions inherent in being a person with a disability. I focused less on overcoming and more on charting my own path. The option of passing as hearing had provided me with a sense of privilege, because others often forgot I was deaf. But passing had also created deep internal dissonance and unhappiness; in fact, I know now, trying to pass as hearing further disabled me.

I saw my last movie without subtitles about ten years ago, realizing it was no longer enjoyable to get only part of the story. My daily world was already one of filling in the blanks when only able to lipread part of a sentence, of getting Bs in a course because I had studied the wrong material. I didn’t need to add to my world of already missing out.

Today, I continue to live mainly in the hearing world, and missing out on conversations is still difficult. But I no longer experience my deafness as a loss that is suffered. Rather, I feel a kind of comfortable ambivalence, and it is in this ambivalence that I’m able to help my therapy patients sit in uncertainty while cultivating a relationship with their own visible and invisible identities. I have come to realize that there is beauty in the fragments, as it creates space to delight in the imagination, to create a different, more interesting story than the one in front of me.

This article appeared in the fall 2016 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

Have an opinion to share?

Pitch your topic at quarterly@mtholyoke.edu.

October 12, 2016

Leave a Reply