Art Breaks Out of the Frame

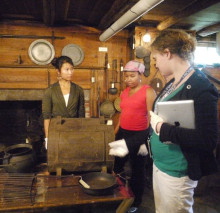

Many of professor Renae Brodie’s first-year biology students start the semester confident that they know what to expect in an introductory science course. But one day during the first few weeks of class, they’re analyzing not cell structure under a laboratory microscope but a seventeenth-century Flemish painting—in the MHC Art Museum. Applying the scientific process in a new setting, they observe a painting from a distance for several minutes, then move closer to note details. Finally, they describe and explain the paintings to one another, offering evidence for their interpretations.

Brodie’s students are hardly alone. Sixty-two professors in twenty-six academic disciplines brought their students to the museum in the past year. In fact, eighty-five courses held at least one class session in the Art Museum.

What’s the draw? Learning skills that will help students succeed now and long after graduation. John Stomberg, museum director, has a vision of the museum as a campus crossroads where art meets ideas—and students—of all kinds. And the vision is becoming reality.

For the past four years, Ellen Alvord ’89 has been the museum’s primary connection to faculty and students. As its Mellon Foundation–funded coordinator of academic affairs, she helps professors shape lessons and select which of the museum’s 17,000 objects best fit each class. Alvord is busy: the museum logged 2,782 student visits last year. (Some students visited in more than one course.) One of her office file drawers is labeled “Ellen’s hatchery,” and indeed many inventive ideas have incubated there. “We’re reexamining what a liberal-arts college can provide in the twenty-first century that’s important and relevant to training the leaders and innovators of tomorrow,” she explains.

What future leaders need—and what Stomberg and Alvord believe the museum can help students develop—is captured in a multiyear plan emphasizing three things: working across disciplines, developing creativity, and enhancing visual literacy.

Working Across Disciplines

Interdisciplinary work was an early success. Alvord says the museum is “a natural place to have people experiment with new ways of teaching. Faculty here have interdisciplinary interests and are willing to try new things.”

Biologist Caleb Rounds teamed science majors with art majors and had them use wooden dowels and elastic bands to create sculptures that could be compressed without breaking. This illustrated the concept of “tensegrity” (tension plus structural integrity) central to the work of sculptor Kenneth Snelson, whose work graces the museum’s contemporary . Elise Croteau-Chonka ’13, who visited the museum with a biology class, says, “the work strongly emphasized the intersection between disciplines that I am looking for as a student at a liberal-arts institution.”

Some exhibitions are particularly adaptable for interdisciplinary use. Professors in fourteen disciplines used the recent exhibition Kara Walker: Harpers’ Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), in which the contemporary artist comments on race and racism by altering nineteenth-century prints. Students in English professor Sara London’s course Verse wrote poetry collaboratively in response to this exhibition. History students in professor Mary Renda’s US Women’s history Since 1890 course compared Walker’s visual work with a century-old essay on the same topic by activist/journalist Ida B. Wells. “The way students got to interact in the museum with one another, with the visual material, and with the reading set the tone for what became one of the most terrific courses I’ve ever taught,” says Renda.

Art history and anthropology classes joined forces to shape the 2011 exhibition transported and translated: Arts of the Ancient Americas, proposing ideas as teams, revising them, then making final decisions on the show’s themes, title, contents, even the color of the walls. That exhibition turned up in unexpected courses too, such as Explorations in Algebra. Coteachers Charlene and Jim Morrow used it to help students think visually about the abstract concept of symmetry. “It is at the heart of much higher-level algebra, and our visit to the Art Museum played a crucial role in deepening students’ understanding,” they say. Using Transported and Translated objects, students discovered ways symmetry was used functionally and as decoration. The Morrows say, “It was fascinating to hear students’ surprise and delight in seeing all the symmetry in the world around them.”

Stomberg says the museum collection’s depth and breadth serve the College well. “We’ve found that some of the best-quality objects in the collection are also the best teaching objects—ones that professors return to again and again,” he says. Take, for instance, Masaniello, a nineteenth-century French oil painting depicting a workers’ revolt against Spanish rule. A biologist will talk about how the artist’s use of red makes the retina perform a certain way; a historian or theatre professor might focus on the soldiers’ uniforms; and social scientists will talk about the class differences depicted. “They’re all having meaningful engagements with the same work of art, but each is totally different from the others,” says Stomberg.

Creativity Can Be taught

Many people believe that creativity is something one either has or lacks. Stomberg disagrees, and has adapted the work of Steven J. tepper of Vanderbilt University, who argues that creativity can be learned by practicing these behaviors:

- Observing closely

- Approaching problems in nonroutine ways

- Asking “What if ?”

- Risking failure and facing uncertainty

- Revising and improving through critical feedback

- Communicating in multiple ways (speaking, writing, etc.)

- Working collaboratively

“We believe creativity can be encouraged through our role as the creativity crossroads on campus,” explains Stomberg. This matters, he says, because “almost every field of endeavor identifies creativity as one of the most salient characteristics of emerging leaders.”

The “creative campus” movement sparked by Tepper is widespread, but having an academic art museum take the lead role in fostering these skills is new, according to Ellen Alvord. The Matisse Foundation recently awarded MHC’s museum a grant for this innovative initiative.

Learning to Analyze What We See

This generation of college students has grown up bombarded by visual images but in many cases hasn’t been taught how to think critically about them in the same way they’re taught how to analyze written or spoken material, says Stomberg. “More than ever, we have to develop visual literacy, by extending critical thinking to the visual world.”

English professor Elizabeth Young does this with her first-year students. They have read Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, and yann Martel’s The Life of Pi for a seminar on The Nonhuman, and now they’re looking at artworks featuring dogs, horses, and insects. Young inquires, “What do you see? What choices has each artist made? What’s ambiguous? What’s missing?”

Patiently, she solicits observations and interpretations to develop students’ descriptive language skills. Works ranging from Henry Fuseli’s eighteenth-century fantasy painting “The Nightmare” to William Wegman’s contemporary photograph of a dog draw reflections on power, class, gender, and wildness vs. domestication.

“This museum experience is revelatory for students,” says Young. When she asked them to write about a museum object, she recalls, “they did very well and seemed to enjoy it too. It is the rare paper assignment where students have complained that they wished the paper were longer!” Young adds that her use of the museum “has been unquestionably one of the highlights of the last few years, and has deepened my own scholarship as well as my teaching and collegial life at Mount Holyoke.”

For both students and faculty, one benefit is clear: “A chance to slow down and observe closely is a luxury these days, and the museum is the perfect place to hone this skill,” says Alvord.

New Life for an Old Museum

Mount Holyoke students have learned from art since its earliest days. But the Art Museum serves a particularly important purpose in this digital age, according to John Stomberg. “The more we digitize, the more people come to the museum as a place for real-life engagement with objects that exist only in one place,” he says. “When students hold a Rembrandt or an ancient Roman coin in their hands, something astounding happens. Our 137-year-old museum is taking on the challenge of being a generator of ideas relevant to the future, not just a storehouse for the past.”

—By Emily Harrison Weir

This article appeared in the spring 2013 issue of the Alumnae Quarterly.

April 10, 2013